People

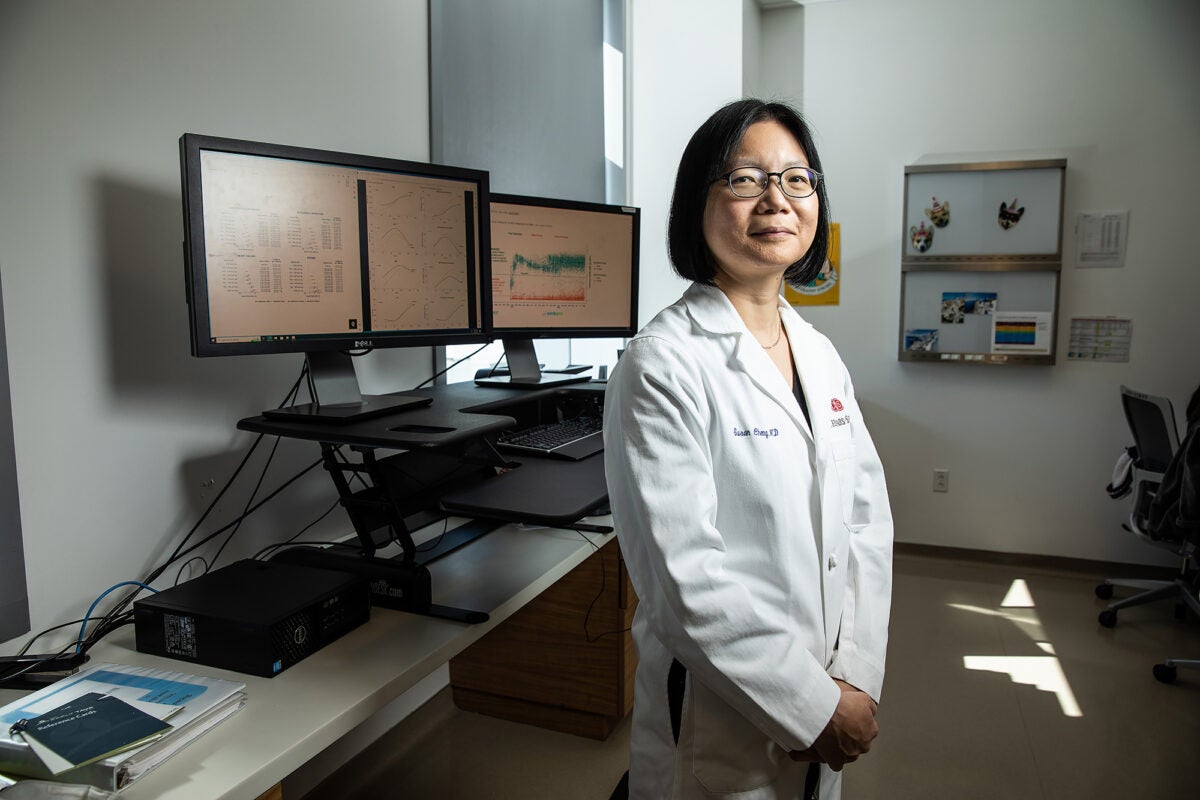

Susan Cheng is exploring the mechanics of healthy aging

The pattern had been there in the data for decades, just waiting for someone to connect the dots: Women’s blood vessels age more quickly than men’s, putting them at risk for hypertension at a younger age. For cardiologist and epidemiologist Susan Cheng, the finding was the serendipitous result of looking at old data in a new way. Three years—and a swerve into COVID-19 research—later, she’s scaling up an ambitious research program to further explore the mechanics behind staying healthy as we age and the reasons why it comes so much easier to some than others.

Cheng is the director of the Institute for Research on Healthy Aging at the Smidt Heart Institute, and the Erika J. Glazer Chair in Women’s Cardiovascular Health and Population Science at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. A graduate of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Clinical Effectiveness program, Cheng also completed a cardiology fellowship at Brigham and Women’s Hospital where she stayed on as clinical faculty and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School. She expected to stay at Harvard for the duration, but then Cedars-Sinai offered her the opportunity to build a new research program where there was a blank slate—a completely open space for her to fill. She was intrigued by the challenge.

She started at Cedars-Sinai in 2018 and the next year jumped at the chance to apply for a center grant from the National Institutes of Health focused on sex differences in disease outcomes. Cheng and her colleagues spent a month poring over decades of population health data before hitting on the idea of changing the way they looked at blood pressure trajectories. Instead of comparing women to men, they compared women to women and men to men. Through this analysis, it became clear that women could become hypertensive at an accelerated rate—suggesting to Cheng that the threshold for what is considered healthy blood pressure should be perhaps lower for women than for men.

The study made a splash when it was published in JAMA Cardiology in January 2020, including even a featured segment on Good Morning America. But plans for follow-up work soon had to be put on hold as the world pivoted to the pandemic.

Uncovering differences in COVID immune response and healthy aging trajectories

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center began treating large numbers of COVID patients early in the pandemic. Cheng and her colleagues quickly realized that that the health data being collected for this rapidly growing patient population could hold important clues about the mysterious disease. So, she agreed to drop everything—assuming it would only be for a few months until the crisis blew over.

The Coronavirus Risk Associations and Longitudinal Evaluation (CORALE) study launched in March 2020, starting with an intensive dive into the electronic health record to discern patterns of risk among the hospitalized patients. In parallel, Cheng’s team set out to measure COVID antibodies and collect symptoms data for any health care worker who was willing to participate. The team was quickly overwhelmed by the number of people who wanted to enroll. “I’m used to running cohort studies where we spend two to three years working to recruit 2,500 patients,” she says. “When CORALE started, we were enrolling 800 people a day.”

The researchers have tracked participants’ COVID infections and vaccinations, hoping to gain insight into the factors that influence immune response. Throughout these studies, participants have been able to access information about their antibody levels, as well as reference data showing where each of their antibody measures fall in comparison to others in the study. For most people, antibody levels jump up after receiving a vaccine dose and this is a signal of a robust immune system. But for others, including those with known immunocompromising conditions, the antibody response is flat or muted and it takes multiple additional vaccine doses until a response is seen.

During rotations as a cardiologist consultant on the wards at Cedars-Sinai, Cheng had plenty of opportunity to observe the treatment of patients with COVID—and to wonder why some people had such different health trajectories than others.

So far, Cheng and her team have found that men are more vulnerable to acute COVID illness than women, but women appear more susceptible to aftereffects such as long COVID—even after adjusting for age and chronic conditions. They also found that during the Omicron surge last winter, many participants had a SARS-CoV-2 infection that they were not aware of, and that Black and Latino health care workers were more likely to have had an infection than their co-workers.

Under Cheng’s leadership, CORALE has grown in scope and ambition into a longitudinal study asking broader questions about health outcomes over the life course. Hopeful that the emergency phase of the pandemic is receding, Cheng and her colleagues expanded the cohort to include a broader diversity of participants and renamed the study EMBARC (Embarking Beyond Acquired Risks in Communities).

“We used to think that once the human genome was coded, we were going to cure all disease. It is now clear there is much more work to do.”

Susan cheng

Cheng says that she is looking forward to reorienting towards the original research mission: to eliminate the barriers to sustaining health as we age, including the two most common causes of death, cardiovascular disease and cancer. A major part of the puzzle is figuring out why some people stay healthy as they age—sometimes despite a lifetime of unhealthy behaviors like smoking—and others do not.

“We used to think that once the human genome was coded, we were going to cure all disease,” she says, “It is now clear there is much more work to do. By the time we reach age 60, or age 80, our health status has so much to do with how we’ve lived our lives. And that piece is a lot harder to measure.”

From web design to medical school

As devoted as she is to her work, Cheng came to it by a circuitous path. Born in Hong Kong, she moved with her parents to England and Canada before landing at Harvard as an undergraduate. Although medical school was always in the back of her mind, she first explored other outlets for her altruistic energy. She volunteered at a local community center teaching ESL and GED classes and after graduation joined a friend’s internet startup. Policy and public health started to beckon—she designed the New York City Department of Health’s first restaurant inspection website—but so did medical school. She applied, but declined her acceptance.

“I got the stomachache of my life, telling me that I’d made the wrong decision,” Cheng says. Luckily, there was time to change her mind.

Cheng went on to earn a medical degree from McMaster University in Ontario, Canada, and completed a residency in internal medicine at Johns Hopkins Hospital, and fellowships at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

As a Brigham cardiology fellow, Cheng learned about Harvard Chan School’s acclaimed Clinical Effectiveness program, which she describes as an opportunity for clinicians with research questions who need the tools to answer them rigorously and systematically. While the training wasn’t required, it quickly became clear that it was essential, Cheng says.

“Fellows would meet at the Brigham, and if you didn’t have that training, you wouldn’t be at the same level as everyone else. You’d sit there thinking, ‘How do I develop the knowledge and skills to be part of the conversation?’”

The pandemic further pushed Cheng to want to be one of the scientists making a difference. She recalls being told by a mentor years ago that epidemiologists don’t save lives. The best they can hope for is that one of their observations will spur a clinical trial. But the urgency around COVID forced Cheng and her colleagues to move quickly and find ways to directly share their results with the public. Even as she shifts from the pandemic to refocus on healthy aging, these new ways of working will continue, she says.

“The pandemic helped us understand that we can do work that can impact outcomes—sometimes immediately,” Cheng says. “We’ve seen that epidemiologists can save lives.”

Photo: John Davis