Ideas

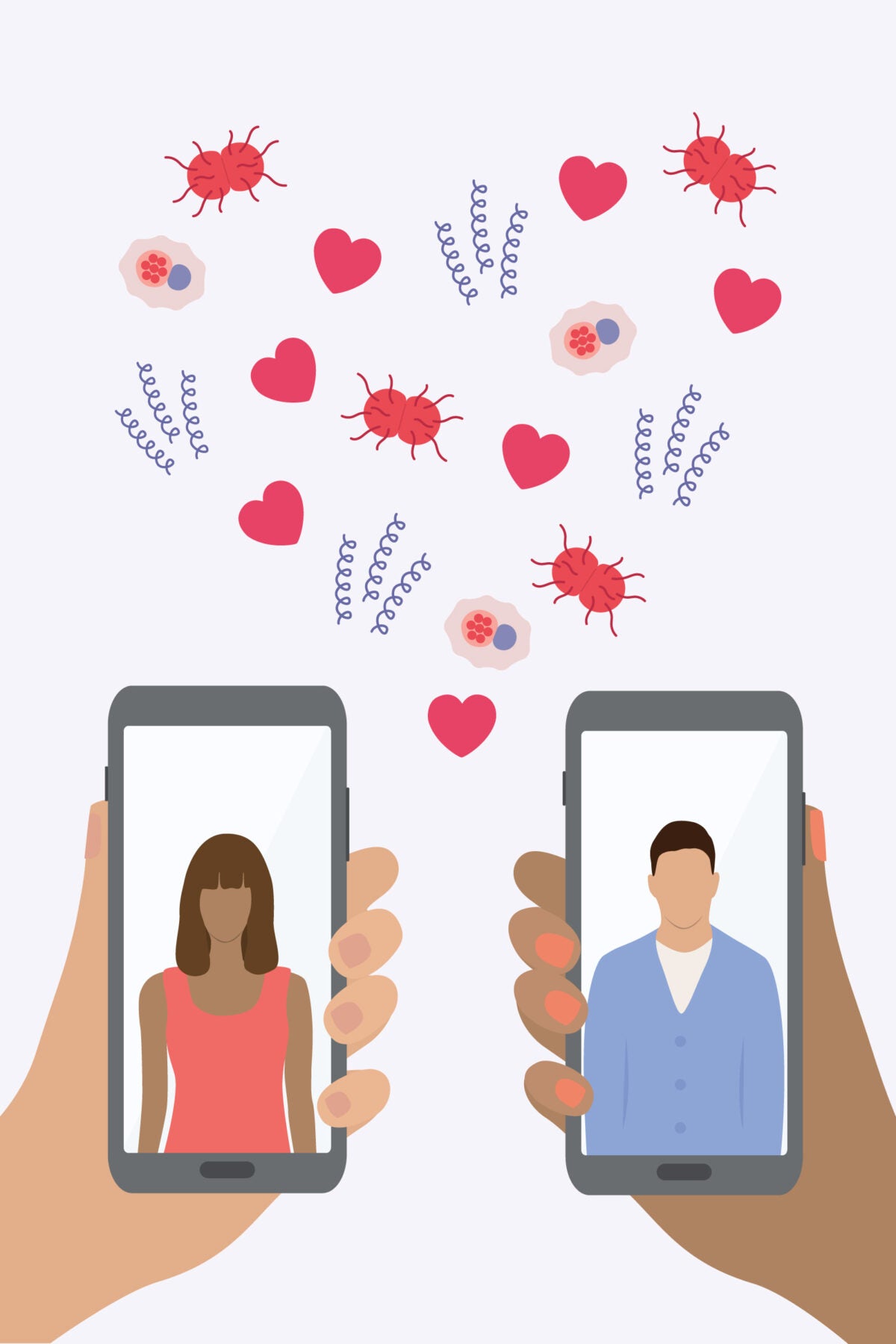

Using Tinder to trace syphilis

Heather Meador is probably one of the few people whose employer allows them to scroll dating apps at work. But the public health nurse isn’t looking for love. She’s searching for people with syphilis.

Over the past decade, rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have surged across the U.S. Stopping the spread of conditions such as syphilis involves contact tracing—reaching out to an infected person’s sexual partners to offer testing and treatment. But if someone doesn’t have a name and phone number for their last partner, follow-up can be almost impossible. That’s where the dating apps come in.

“The way we used to connect just isn’t working any more. We needed another tool in our toolbox,” says Meador, clinical services director at Linn County Public Health in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. She needed a different avenue for syphilis contact tracing, one better aligned with the ways many people now meet their partners—even if the disease in question is one associated with bygone centuries. With her boss’s blessing, Meador created accounts for Linn County Public Health on dating apps such as Tinder, Grindr, and Bumble. She used those accounts to contact the sexual partners identified by her patients at the clinic. She kept her messages succinct, telling app users she would like to speak with them about a personal matter and directing those who responded to testing and treatment for any STI.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

The initiative is part of a growing effort to use new technology, such as dating apps and chatbots, to tackle a very old disease. In the pre-antibiotic era, as many as one in 10 Americans were thought to have been infected with Treponema pallidum, the corkscrew-shaped bacterium that causes syphilis. Left untreated, the disease can lead to neurological damage and even death. Infections during pregnancy can cause miscarriage or lifelong health problems for the baby.

With the advent of penicillin in the 1940s, cases plummeted. Rates rose again in the late 1980s, due to the abuse of illegal drugs, the rise in HIV, and other factors, but by 2001, only two Americans per 100,000 were infected with syphilis, after a campaign to eliminate the disease by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Ironically, however, the very success of these programs meant that cash-strapped health departments often siphoned funding to more pressing issues, according to Elizabeth Finley, director of communications at the National Coalition of STD Directors. With fewer resources devoted to labor-intensive processes like contact tracing and patient follow-up, syphilis cases have increased almost five-fold in the last two decades.

While research suggests that dating apps and the anonymous hookups they facilitate may be one factor fueling these increases, Antón Castellanos Usigli, a health care consultant in New York City, thinks the apps could also become a key component of STI prevention. In 2016, he created profiles on several dating apps to promote condom use, testing, and pre-exposure medicines (PrEP) among men who have sex with men. “We need to get back into thinking as a community, as public health practitioners and businesses that have a stake in this issue,” says Usigli. “How can we address STI prevention in this new era?”

Usigli expanded his research while earning his doctorate at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Between May and November 2021, his app-based outreach provided sexual health tips to 2,271 people and led 136 people to schedule clinic appointments. One quarter of those who showed up to appointments tested positive for STIs, and 24 percent began taking PrEP. People who identified as men who have sex with men engaged with the apps’ peer sexual health outreach accounts nearly 10 times more than they did with targeted advertisements.

Meador achieved similar success using dating apps for contact tracing, claiming a 75 percent response rate. She says that while some individuals are angry to learn they may have been exposed to an STI, most are grateful for the opportunity for testing and treatment.

Word of these new approaches is spreading. The CDC has fielded so many tech questions related to STI contact tracing that they created a special working group to address the topic. The CDC and Emory University partnered with Grindr to provide the app’s users with free at-home HIV test kits. And a group of teens in Syracuse, New York, built a chatbot named Layla that answers sexual health questions and offers the location of the nearest sexual health clinic.

But just as public health professionals are starting to harness tech to battle back surging STI rates, the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 (passed in the spring to resolve the debt ceiling issue) eliminated $1.3 billion from the CDC’s 2024 budget, slashing funds distributed to states and counties for local programs such as contact tracing and disease prevention. To Meador, it feels like a huge step backward, and she has already cut some nurses back to part-time, leaving fewer staff to trace contacts and provide treatment.

“We have more work and fewer dollars to spend,” she says.

Source illustrations: CreativeDesignArt / iStock, Anastasia Usenko / iStock