School news

Of note Spring 2022

Portrait honors Bernard Lown’s legacy

A new portrait of beloved emeritus professor Bernard Lown now hangs in the Department of Global Health and Population. Lown, renowned for his work in cardiology, global health, and humanitarian causes, and co-founder of an organization that won a Nobel Peace Prize, felt the photo “The Kashmiri healer” captured the empathy embodied in the art of healing. Painter Stephen Coit used the photo, which hung in Lown’s examination room and later his living room, as inspiration for the painting’s background. Read more about Lown.

When “good” cholesterol isn’t good

When it comes to heart disease, it’s well-known that low-density lipoprotein is “bad” cholesterol that can clog up artery walls and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) is “good” cholesterol that helps clear cholesterol out of the system. But drugs to boost the amount of HDL in the blood failed to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and were never brought to market. Jeremy Furtado, Frank Sacks, and colleagues in the Department of Nutrition may have found a reason why. They had already identified several protein-defined subspecies of HDL, some of which were associated with an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease. In a December 2021 paper they confirmed the failed drugs actually increased the proportion of detrimental HDL more than the protective HDL. The researchers are continuing to study HDL subspecies and their varying functions, with the goal of identifying beneficial therapies and dietary interventions.

Epstein-Barr virus is the leading cause of multiple sclerosis

Harvard Chan School researchers have been able to establish that the Epstein-Barr virus is the likely cause of multiple sclerosis (MS). Epstein-Barr’s link with MS, a potentially disabling disease of the central nervous system for which there is no cure, has long been suspected, but proving a causal relationship has been difficult. In a study published in Science in January, researchers, including Alberto Ascherio, professor of epidemiology and nutrition, analyzed blood samples from U.S. military personnel. They found the risk of MS increased 32-fold after infection with Epstein-Barr but was unchanged after infection with other viruses. What’s more, serum levels of a biomarker of the nerve degeneration typical in MS increased only after an Epstein-Barr infection. Ascherio, the study’s senior author, says the findings suggest stopping Epstein-Barr infection could prevent most MS cases, and that targeting the virus could lead to a cure for MS. There are an estimated 2.8 million people living with MS worldwide. Research suggests global prevalence is rising.

Newly identified hormone may be critical diabetes driver

Fabkin, a recently discovered hormone that helps regulate our metabolism, may play an important role in the development of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, according to work led by the Sabri Ülker Center for Nutrient, Genetic, and Metabolic Research at the Harvard Chan School. The study showed that mice and human patients with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes had abnormally high levels of the hormone in their blood. When the researchers blocked the activity of fabkin in mice, it prevented development of both forms of diabetes. Fabkin likely plays a similar role in humans, making the hormone complex a promising therapeutic target, according to the researchers. “The discovery of fabkin required us to take a step back and reconsider our fundamental understanding of how hormones work,” says lead author Kacey Prentice, research associate in the Sabri Ülker Center and the Department of Molecular Metabolism. “I am extremely excited to find a new hormone, but even more so about seeing the long-term implications of this discovery.”

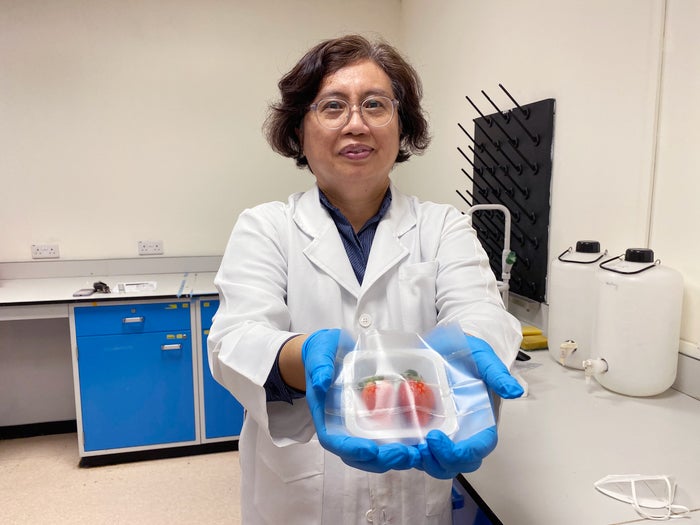

‘Smart’ packaging Preserves Food, Planet

Using corn protein and other naturally derived biopolymers, scientists from the Harvard Chan School and Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University (NTU) have developed a biodegradable “smart” packaging material that extends the shelf life of food and reduces plastic waste. It contains flexible nanoscale fibers that release natural antimicrobial compounds when exposed to an increase in humidity or enzymes from harmful bacteria. This protection is provided only when needed, minimizing the use of chemicals and preserving the taste and composition of the food. Philip Demokritou, director of the School’s Nanotechnology and Nanotoxicology Center, co-led the research.

What led to the opioid crisis—and how to fix it

Without urgent intervention, 1.2 million people in the U.S. and Canada will die from opioid overdoses by the end of the decade, in addition to the more than 600,000 who have died since 1999, according to a February report from the Stanford-Lancet Commission on the North American Opioid Crisis. Howard Koh, Harvey V. Fineberg Professor of the Practice of Public Health Leadership and a member of the Commission, called the opioid crisis a “multisystem failure of regulation,” citing Purdue Pharma’s fraudulent description of the drug OxyContin as less addictive than other opioids as one egregious example. The report offers recommendations, including curbing pharmaceutical industry influence, promoting safer opioid prescribing initiatives, and integrating addiction care into mainstream health care.

Harvard Humanitarian Initiative providing assistance in Ukraine

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has prompted a massive humanitarian crisis, with mounting military and civilian casualties and millions of people on the move to escape the violence. The Harvard Humanitarian Initiative (HHI) has had a longstanding relationship in eastern Ukraine and is supporting health care and public health services for those affected, says HHI Director Michael VanRooyen. This includes coordinating the placement of physicians from Harvard-affiliated hospitals to assist and providing equipment and supplies to relief agencies and hospitals. Its experts are also supporting the World Health Organization by helping train first-line responders in emergency first aid and in the techniques of negotiation so that they can safely access populations in need. Watch a March 29 Q&A with VanRooyen.

Olive oil linked to longevity boost

People who consume higher amounts of olive oil may lower their risk of premature death overall and from specific causes including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative disease, compared to people who never or almost never consume olive oil, according to a Harvard Chan School-led study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology in January. The researchers also found that people who consumed olive oil instead of animal fat had a lower risk of total and cause-specific mortality. Marta Guasch-Ferré, a senior research scientist in the Department of Nutrition, says, “Our findings confirm current dietary recommendations to replace animal fats with plant oils for the prevention of chronic diseases and premature death.”

Documenting environmental injustice

Discriminatory regulations, policies, and practices have meant people from racial and ethnic minority groups are more likely than others to live in places that expose them to environmental hazards, such as air pollution and lead contamination, resulting in health disparities. Harvard Chan School experts explore the problem in a new Boston-centered interactive web series. There’s also new evidence that such environmental racism appears to be widespread in the U.S. Francesca Dominici, Clarence James Gamble Professor of Biostatistics, Population, and Data Science, collaborated with the Environmental Systems Research Institute to link 17 years’ worth of demographic data from across the country with data on PM2.5—fine particulate pollution. They found that areas with larger white and Native American populations have been consistently exposed to average PM2.5 levels lower than those with larger Black, Asian, Hispanic, or Latino populations. The study was published in January in Nature.

Bridging the gap between cancer research and policy

“We know a lot about how to prevent and detect cancer, but we’re not great about turning that science into effective policies,” says Karen Emmons, professor of social and behavioral sciences at the Harvard Chan School. As an implementation scientist, Emmons is focused on “taking what we know and making it what we do.” She recently co-authored a commentary in Translational Behavioral Medicine, arguing that in order to increase the use of scientific evidence and improve health equity, the field needs to do a better job of engaging with the policymaking process. This includes focusing beyond just getting a bill on tobacco taxes passed, for example, to understanding the conditions that would make such a bill effective. In addition, she notes that partnerships outside of government can be key to ensuring that everyone benefits from health policies such as paid time off for cancer screenings, and that a policy’s impact on disadvantaged groups is considered.

Top photo: Kent Dayton / Harvard Chan School