Opinion

Mpox offers another chance to confront vaccine inequity

This article was originally published by Undark.

On Aug. 14, the World Health Organization named mpox a global public health emergency—for the second time in two years. When the first declaration was issued in 2022, preexisting smallpox vaccines offered hope that the mpox virus could be controlled more quickly than SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19. However, similar inequities in vaccine access and scant international cooperation marred sustained containment efforts.

For years, mpox has been spreading in Central and West Africa, where two lineages of the virus have become endemic. Spanning from Sierra Leone to Nigeria and parts of Cameroon, clade II typically causes less severe disease with lower mortality than its counterpart clade I, which is found in the Congo River Basin and bears fatality rates of up to 10 percent. A new variant from clade I is currently responsible for the high disease burden in the Democratic Republic of Congo—and, for the first time, cases in nearby Burundi, Rwanda, Kenya, and Uganda—and has stoked the international emergency. Sweden and Thailand have also recently identified the variant in travelers arriving from the region. Nevertheless, the continent facing the brunt of mpox still sorely lacks vaccines, with 10 million doses needed but only 200,000 becoming available as of mid-August, according to Jean Kaseya, director-general of the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This injustice has a long arc.

From yellow fever to Ebola, Africa has been consistently shortchanged on essential supplies to tackle infectious diseases. During the Covid-19 pandemic, African countries experienced delays in receiving their fair share of personal protective equipment, antivirals, and other resources, despite being expected to participate equally in disease control. For mpox, none of us are surprised about the recurrence of uneven vaccine access; this has been a persistent motif in global health.

We are sympathetic to the reasons why Western countries, faced with the possibility of mpox, would prioritize their own vaccine needs. But this speaks to the predicament of balancing self-interest and equity.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

One proposal to expand vaccine access is through donation-based schemes, which don’t always work. Take for example the Covid-19 Vaccines Global Access Facility, or COVAX—a large-scale, public-private partnership designed to enhance equitable distribution of Covid-19 vaccines. At the end of 2021, the G7 and European Union had a collective surplus of nearly 770 million Covid-19 vaccines while COVAX simultaneously fell 1.5 billion doses short. Africa specifically saw a deficit of just under half a billion Covid-19 vaccines that would have been critical for meeting its annual vaccination objectives. In a familiar retelling of this story, just before the WHO first labeled mpox an emergency, North American and European countries bought up and stockpiled millions of doses of an mpox vaccine produced by Bavarian Nordic.

As such, moving towards equity means first shifting away from a consumer to a producer model. Some pharmaceutical companies currently have end-stage fill and finish manufacturing in Africa for drugs and vaccines, which entails loading bottles with pills and preparing syringes for distribution. However, sustainably addressing vaccine inequity will require a homegrown effort to build the whole pandemic value chain—the end-to-end process of vaccine manufacturing—on the continent.

There are some promising signs ahead. When the 2022 mpox outbreak was ramping up, the Partnerships for African Vaccine Manufacturing, or PAVM, unveiled a Framework for Action to expand the continent’s vaccine manufacturing capacity to satisfy 60 percent of its own supply in the next two decades. Importantly, the framework places Africa in the driver’s seat, establishing pooled procurement mechanisms, a formalized process for preparing and financing manufacturing deals, and a unit that can promote enough technology transfers to generate at least 1.5 billion vaccine doses annually within this timescale.

While Africa will steer this effort, it need not do all the work alone. In fact, PAVM’s framework explicitly summons all parties “to play their part in bringing us to ‘the Africa we wish to see.’”

These contributions must be multifaceted. First, the WHO should encourage pharmaceutical companies to participate in technology transfer so that Africa can meet its vaccine manufacturing goals. Though potentially challenging due to intellectual property law, there is precedent: In 2022, Bavarian Nordic announced a technology transfer agreement with Michigan-based Grand River Aseptic Manufacturing. At the time, the company’s chief financial officer, Henrik Juuel, told Reuters that interest in their mpox vaccine was “overwhelming.” A similar pivot towards Africa is long overdue and attainable with robust international pressure. The initial success of South Africa’s WHO-sponsored hub for mRNA vaccine technology underscores Africa’s readiness to meet the pharmaceutical industry and other global stakeholders halfway.

Second, international partners can support the homegrown expansion of research and development capacity within Africa, ensuring that countries have the tools to proactively address their own health needs. For example, PAVM’s framework emphasizes opportunities to bolster the continent’s pharmaceutical value chain, such as increasing the number of animal research facilities and creating a coordinating platform for large-scale R&D activities. Industry and academic affiliates can further encourage these ongoing efforts by plugging African scientists into their knowledge networks and research collaborations.

Third, alongside expanding vaccine manufacturing, Africa should lean into its time-tested strengths for infectious disease control. For example, community networks on the continent have historically facilitated robust contact tracing, public messaging, and isolation of cases during outbreaks. Such community-based practices have also established a tradition of prioritizing the vaccine needs of high-risk groups like health care workers, a pragmatic strategy that should be used to manage mpox until more doses are available.

More broadly, we should revisit how Africa is treated in future global health affairs. For starters, the WHO can rally development institutions and nongovernmental organizations to serve as a countervailing force to vaccine nationalism and myopic private interests. This may entail the WHO redefining its scope of authority and reforming the levers it can employ when member states inappropriately engage in rampant vaccine hoarding. To this end, some legal scholars have advocated for the organization to eschew wide-reaching global health governance in favor of a sharper focus on infectious diseases, a concentrated approach that could enable greater consensus-building among parties.

It is also high time for countries to come back to the negotiating table and ratify a Pandemic Preparedness Treaty—one that reevaluates vaccine-sharing mechanisms to prioritize high-risk regions. For instance, during the first global outbreak of mpox, the WHO announced plans to supply doses to 30 countries outside Africa, despite these countries having lower disease burdens than African countries. Ahmed Ogwell, then-acting director of Africa CDC, in turn, said that “the place to start any vaccination should be Africa and not elsewhere.”

Covid-19 spotlighted how vaccine inequity is persistent, pervasive, and almost inevitable, especially as climate change, population growth, and more frequent human-wildlife contact incite more pandemics. Mpox could be an opportunity to turn the page and rebalance global health priorities.

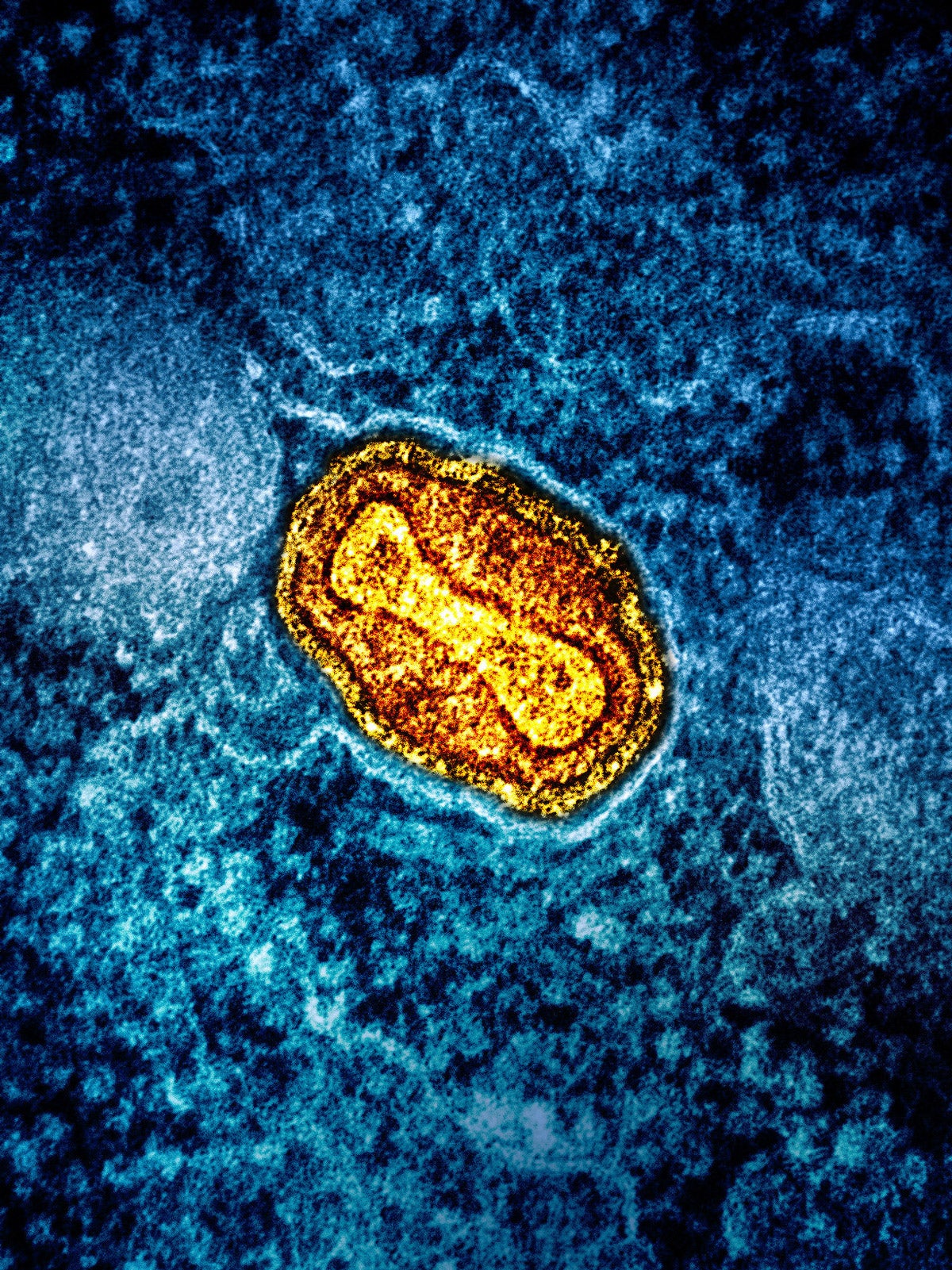

Image: Colorized transmission electron microscope image of a mpox virus particle (yellow) found in an lab-cultured infected cell (blue). (NIAID / NIH)