Feature

Paid family leave needs to expand its definition of “family”

All Charice King wanted was to be by her mother’s side. For more than two years, King helped her mother, Sonya Lee Menyweather, fight an aggressive cancer. King drove Menyweather to chemotherapy appointments; helped manage her care at home; rushed her mother to the hospital for increasingly frequent emergencies. But tending to an ill loved one, while staying ahead of her own bills, proved a complicated juggle.

It was only after her mother died last November that King, a California resident, learned she might have qualified for up to eight weeks of paid family leave for each year she cared for her mother. She was stunned, unable to recall anyone advising her to apply earlier. “I was really struggling,” says King, who is 34 and still faces unpaid bills from the time surrounding her mother’s death. Regular checks to support her while she cared for her mom would have been an enormous help. She had never even imagined such benefits existed.

In fact, such benefits don’t exist for most people in most states. In the few states that do offer paid leave for caregiving, most programs restrict the benefits to immediate family—which leaves out many caregivers. Limiting benefits to blood relatives can have an outsized effect on older Black women, who are more likely to age without living family members than White women and men. Black women are likely to rely on close friends or distant kin, who qualify for paid leave in only a handful of states.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Such restrictions have deep roots. When President Bill Clinton signed the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) 30 years ago, it gave Americans the right to take up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave from a job, but only to care for themselves or a child, spouse, or parent. The bill’s opponents, led by business interests, had successfully pushed to limit the reach of the bill in the belief it would save them money, says Megan Sholar, a political science professor at Loyola University Chicago and the author of Getting Paid While Taking Time. In fact, numerous studies have found paid family leave laws enacted by states have minimal impact on business operations for most employers and can improve productivity and employee morale.

“We need to expand the definition of ‘family’ if you want to be equitable for the Black community. The Black community needs to define who family is for them. For us, family is whomever I trust, who says they’re going to take care of me.”

Carlene Davis, co-founder of Sage: Sistahs Aging with Grace & Elegance

The FMLA also included a number of exceptions—a worker’s employer must have at least 50 employees, and the worker must have been employed there for at least a year and have worked at least 1,250 hours in the previous 12 months. This meant that from the moment it became law, the FMLA excluded about 40 percent of workers. And because it only offered unpaid leave, it was a nonstarter for anyone who couldn’t afford to take time off without pay. The FMLA, touted as bolstering the country’s social safety net, instead has been “a double whammy of economic frailty” for lower-income people, especially people of color and women, says David R. Williams, chair of the department of social and behavioral sciences at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Their need for [paid leave] is greater, although often, because of the kinds of jobs they have, they may be less likely to have worked at a job that actually would qualify.”

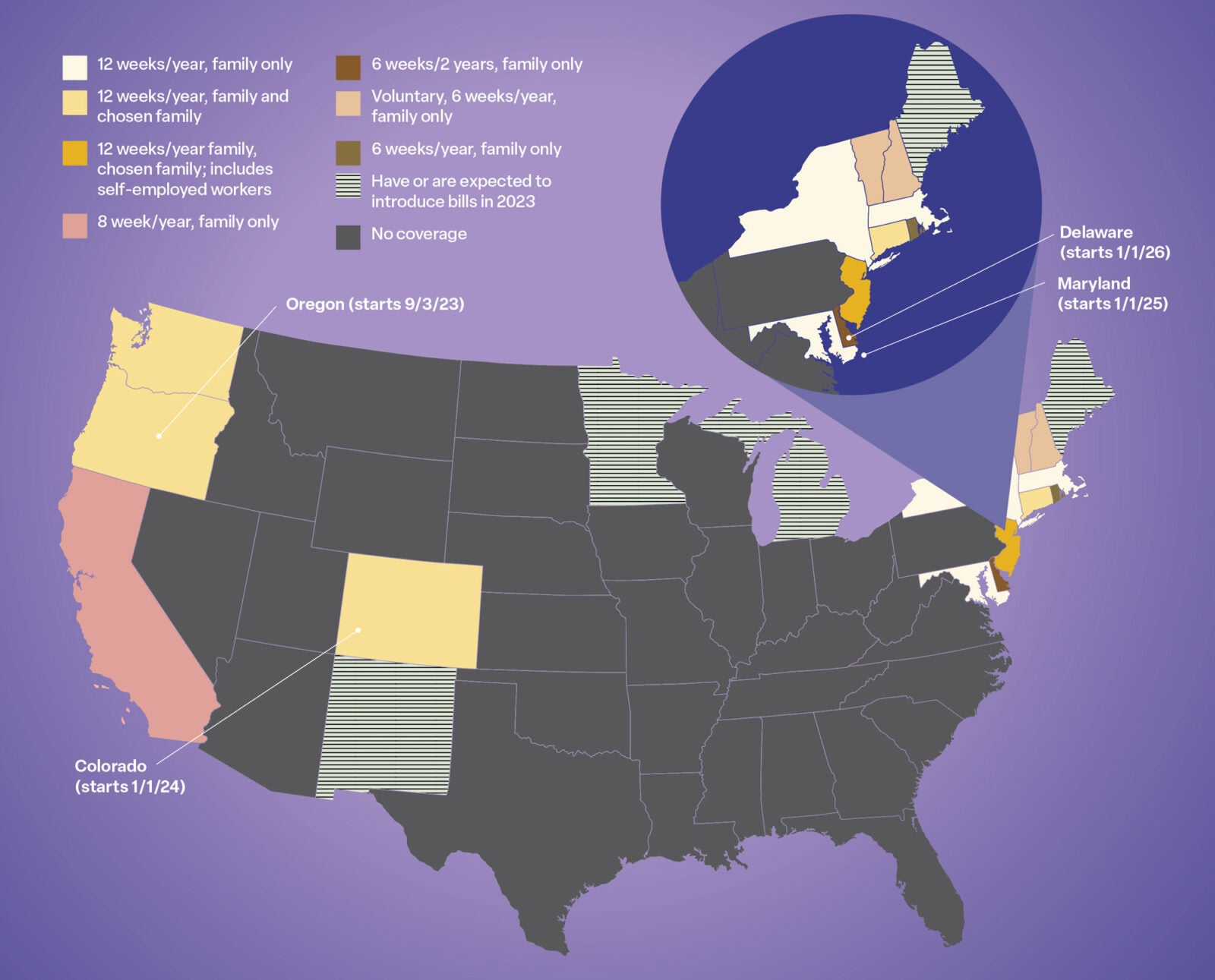

Despite its shortcomings, the FMLA has not been substantively updated even as the U.S. population ages and the need for caregiving grows. By 2034, older adults in the U.S. are projected to outnumber children. The District of Columbia and 11 states have responded with a patchwork of paid leave initiatives, meaning about a quarter of Americans—mostly on the coasts, like King—could be paid for taking leave to care for a family member. Virginia’s Senate recently passed a paid leave bill, which failed in the House, preventing a first in a Southern state. Legislators in at least four more states are either crafting paid leave legislation to introduce in 2023 or have already introduced bills that do.

“We are seeing tremendous momentum,” says Sharita Gruberg, vice president for economic justice at the National Partnership for Women & Families, which advocates for national paid caretaking leave. “Passing in the Virginia Senate is no small feat.”

To fill gaps in the Family and Medical Leave Act, a number of U.S. states and the District of Columbia offer paid family leave. Only a few allow employees to designate non-family members as paid caregivers.

Still, Gruberg often hears about people like King, who don’t know paid family leave exists, and says “it is so infuriating.” Also frustrating is how little we actually know about how people use and benefit from such programs, which means policies aren’t always effective for the people they’re meant to help.

“We need to understand more about how caregivers would like to be able to use paid family leave and how they identify when they need to take time” for caregiving, says Donna Benton, associate professor of gerontology at the University of Southern California and director of the USC Family Caregiver Support Center. Benton says we don’t know such things as what illnesses are more likely to prompt people to take leave, why some people take intermittent leave and why some take it all in one chunk, and why some who are eligible don’t take it at all. Nor do we know how existing family leave policies interact with the cultural norms of diverse communities.

The aging of older Black women is particularly understudied. In 2020, Reginald Tucker-Seeley, then a professor of gerontology at USC, and Carlene Davis, co-founder of Sage: Sistahs Aging with Grace & Elegance, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit, looked at 152 research papers on aging in place. They found only 14 papers specified the inclusion of Black or African-American women in the study. And none of the 101 articles that defined aging in place included race or gender in their definition.

“If we are really serious about ensuring that everyone ages well and has the best health possible, then we’re going have to focus on what that looks like for specific populations,” says Tucker-Seeley, now vice president of health equity at ZERO, a nonprofit trying to end prostate cancer. “A one-size-fits-all intervention is not going to work.”

Research has shown that older Black women live lives with different contours than those of White men and women, and Black women may be more likely than their White or male counterparts to find themselves alone in old age. The number of Black women over 50 who in 2015 did not have a partner, biological children, siblings, or parents was 2.2 percent. That’s more than Black men (1.7 percent) and White men (0.8 percent) and double the number of White women, who were at 1.1 percent. This gap is expected to widen so that by 2060 7.3 percent of Black women will be kinless, versus 2.2 percent of White women. Black people are nevertheless more likely to maintain strong social ties, either to those in their church or neighborhood community, or among networks of extended kin. But most family leave laws define “family” as people related directly by blood or law to the beneficiary, such as spouse, child, parent, grandparent. Only a few states allow caregiving for in-laws or someone without a biological or legal relationship, say a friend, neighbor, or someone from a community such as church.

“We need to expand the definition of ‘family’ if you want to be equitable for the Black community,” says Davis, who herself is single and childless. “The Black community needs to define who family is for them. For us, family is whomever I trust, who says they’re going to take care of me.”

Our social safety net has such enormous holes that it’s actually luck if you’re caught by it.”

Reginald Tucker-Seeley, vice president of health equity at ZERO

Davis has a care team she’s assembled in case she falls ill or becomes disabled and needs help navigating life and the health care system. The team includes two women Davis calls her play daughters, a term common in the Black community for friends who are regarded like kin. These women were previously unable to take even unpaid leave time to care for Davis, but could now, thanks to a change California made to its family leave laws last September allowing residents to designate an unrelated person as a caregiver eligible for unpaid leave. But such nonrelatives cannot access California’s generous paid leave policy, because it remains limited to people with legal or blood relations to the person they are working to help.

That stings, says USC’s Benton. Because Black families like hers have a long history of being broken up dating back to slavery, “we had to build family, whether it was by blood or kinship, and those family ties were needed,” she says, adding “some of this has remained as a cultural norm over the generations.”

Benton herself has a childhood friend she calls her sister but who lacks close blood kin. If this woman needs her, Benton plans to take off work and care for her. As the law stands, if Benton wanted to get paid for her time off, she could take sick leave. But California only mandates that employers provide a minimum of three paid sick days per year. Paid family leave, however, covers up to eight weeks annually.

Nearly one in five Americans provided care to an adult family member or friend in 2020, up from 16.6 percent five years before. Yet paid caregiver leave in any form remains more a dream than a reality for the majority of Americans, despite the documented stress of caring for a loved one, which numerous studies have found puts people at risk for physical and mental health complications. In addition, more than three-quarters of caregivers report spending out of pocket on caregiving, at an average of $7,200 per year in 2021. Caregiving represents a significant financial strain for Black caregivers, who on average spend nearly a third of their income on caregiving, and for Latino caregivers, who spend nearly 50 percent of their income (compared with 18 percent for White people and 22 percent for Asian Americans).

Charice King’s finances were certainly strained, and that was before she lost her job as a middle-school aide in the emotional aftermath of her mother’s death. Newly inspired to tend to a vulnerable population, she started a position this spring as a care manager at a senior living facility in Pleasanton, California.

Still, the debt incurred while her mother was ill gnaws at her psyche. “I haven’t even been able to grieve my mom,” she says. King has filed the paperwork for paid family leave, hoping the state will grant it retroactively “so I can stop worrying about ‘How I’m going to pay this, how I’m going to pay that?’”

Even those whose income and assets are low enough to qualify for Medicaid discover that the waitlist for home health services is more than 650,000 people long.

Addressing the gaps and inequities in the FMLA is just one of the steps needed to bolster caregivers and their loved ones. Tucker-Seeley notes that “our social safety net has such enormous holes that it’s actually luck if you’re caught by it.”

Those holes are likely to get bigger. Between 2021 and 2031, the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects demand for home health and personal care aides will grow by 25 percent. Medicare, which many Americans assume will help pay for some degree of caretaking when they become senior citizens, is already falling short, says Nicole Jorwic, chief of campaigns and advocacy for Caring Across Generations, an advocacy group. “So many people inaccurately think that Medicare is going to have them covered,” she says. In fact, Medicare only pays for home health services under limited conditions. Even those whose income and assets are low enough to qualify for Medicaid discover that the waiting list for those services is more than 650,000 people long.

The U.S. is simply not prepared to care and provide for its aging population, says Harvard’s Williams. “We haven’t as a society come to grips with the depth of the need.”

But at least, on the caretaker front, there is progress. Year by year, more states vote to provide some form of paid family leave. “For so long, in the U.S., the only leave we had was unpaid,” Loyola Chicago’s Sholar says. “And that’s starting to change.”

There is evidence such change expands the reach of family leave. In March the Washington Center for Equitable Growth published work showing paid family leave policies in New York, New Jersey, and California meant women with an ailing spouse were seven percent less likely to quit their jobs. This improvement in job continuity was concentrated among caregivers with 12 or fewer years of education—a group that has typically found it a struggle to take unpaid leave.