Ideas

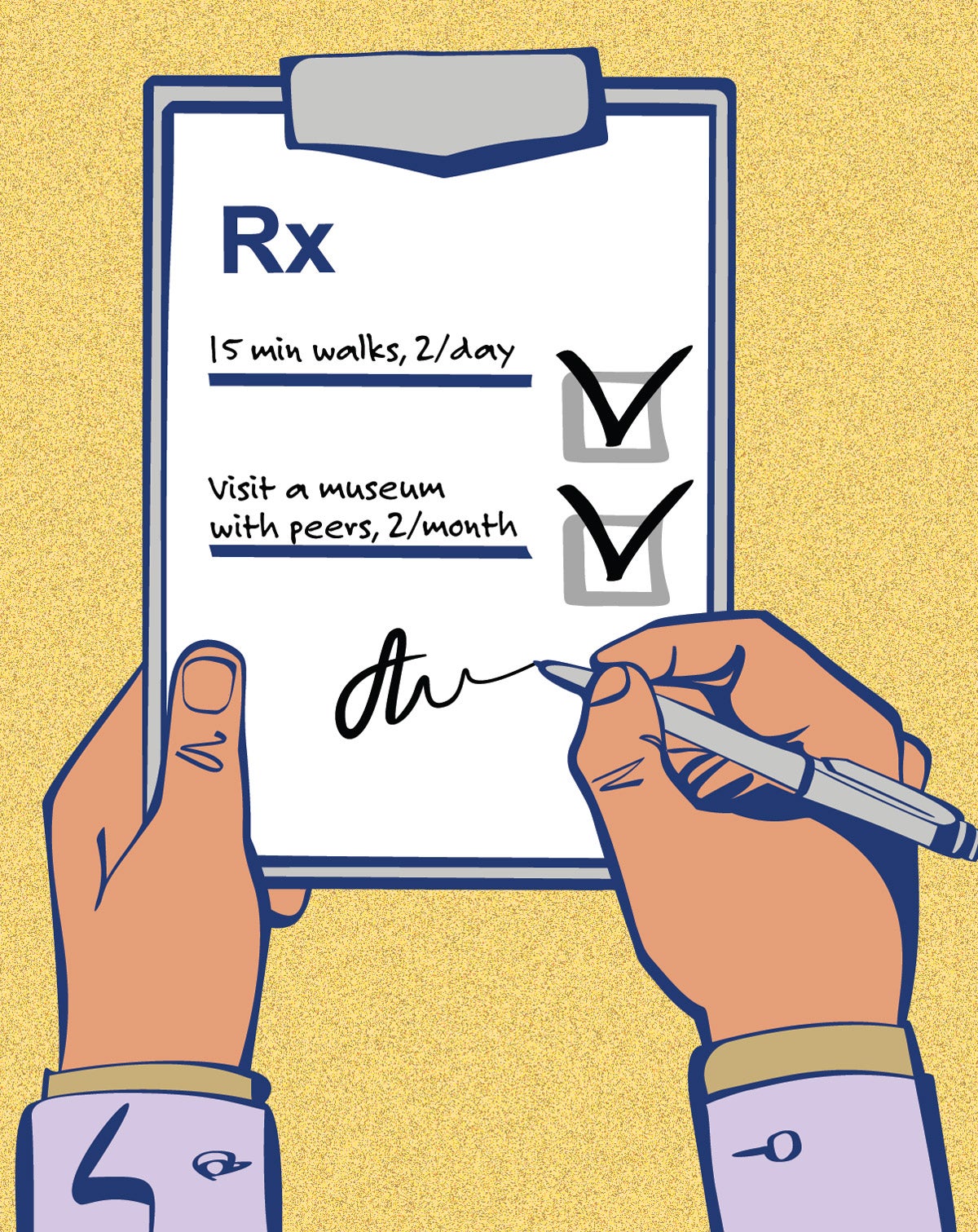

Doctor’s orders—head to the museum instead of the pharmacy

Doctors aren’t known for prescribing museum visits, dance classes, nature walks, or volunteering. But such social prescriptions are now becoming commonplace in more than two dozen countries. And in the spring of 2023 the first U.S. initiative of its kind will let some New Jersey health providers choose whether to instruct patients to attend free arts and culture events.

Social determinants—the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work, and age—are known to shape health. Studies show one in five doctors’ appointments in the United Kingdom are for non-medical reasons such as loneliness, financial stress or poor housing. But doctors don’t treat social conditions, with some exceptions. Instead of a health care model based entirely on pills and procedures, where doctors ask patients, ‘what is the matter with you,’ this concept makes a paradigm shift to asking ‘what matters to you,’” says Bogdan Chiva Giurca, a London-based physician and a champion of social prescribing in the U.K. and globally.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

The U.K.’s National Health Service integrated social prescribing into its programs in 2019. Community health workers known as “link workers” meet with patients and connect them with resources ranging from recreational activities such as book clubs or art classes to social support services such as finding housing aid. Giurca says the consultation also improves health, because it helps patients feel listened to. Link workers are fully engaged with patients, even accompanying them to the activities or finding someone who can.

In the U.S., many doctors have informally applied activities to care. Ardeshir Hashmi, chair for geriatric innovation at the Cleveland Clinic, has long assigned his senior citizen patients a range of activities, including Life Story clubs, a way for seniors to talk about their lives. He says it helps prevent what he calls the “million dollar workout” —spikes in anxiety or other manageable conditions that land patients in an emergency room. “I just didn’t know what I was doing was social prescribing,” he says.

Similarly, Alan Seigel, a family physician who works in the San Francisco Bay Area, started offering NatureRx walks, Walk with A Doc, and expressive arts training programs to the community and to his patients over a decade ago. He says he has seen patients have what he describes as the “most powerful transformational experiences.”

Positive results for patients hold promise, but the concept faces particular challenges in the U.S. For one, the U.S. does not have a national health service, which makes implementation and scaling up more difficult, says André Nogueira, deputy director of the Design Laboratory at the Harvard T.H. Chan School. He was one of the organizers of a workshop held at Harvard in October 2022 that brought together representatives from health systems, insurers, government officials, practitioners, and non-profit leaders to discuss the concept and how to overcome its challenges. Hashmi and Seigel were among the attendants.

Another participant was Chris Rudd, founder of ChiByDesign, a Black-owned design firm in Chicago. Rudd finds the concept promising, but programs must focus on issues affecting marginalized people to counter systemic biases known to create health inequities. “If we design for those on the fringes, the center may be much better served,” Rudd says.

Convincing insurers to reimburse for such programs is another key in the U.S. An initiative to give patients free access to events at The New Jersey Performing Arts Center offers an important early test case. It will be supported by the RWJBarnabas Health System, based in West Orange, New Jersey, and Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield’s philanthropic and social support programs—the first social prescribing effort in the U.S. to have formal support from the philanthropic arm of an insurer. The goal will be to have 1,000 patient referrals in the first year, and to track their results, says Alyson Maier Lokuta, senior director of arts and wellbeing at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center. She adds that the hope is to have enough data by the end of 2024 to encourage private health care partners to create a reimbursement model in New Jersey.

A number of other social prescribing projects in the U.S. are underway. Project Connection, a mental health non-profit in West Valley City, Utah, encourages patients to build connections in their community. Art Pharmacy in Atlanta made about 160 referrals over a six-month period in 2022 for “arts interventions.” The Massachusetts Cultural Council’s CultureRx in December started phase four of a project to show how cultural institutions are part of public health. Connecting these groups and aggregating their results is the mission of Social Prescribing USA, a non-profit that wants to see social prescribing available to every American by 2035. While the idea “isn’t a panacea,” says Social Prescribing USA’s founder, Dan Morse, “it is a new way of thinking and provides a new set of tools you can use to manage wellness.”

Top image: Anastasiia_New / iStock