Feature

North Carolina’s radical Medicaid reinvention

Dawn Verret’s single-wide mobile home was a flurry of activity in early February. She tried to stay out of the way as contractors stripped her small, deteriorating bathroom down to the studs for a total overhaul. They would replace the shower, vanity, toilet, drywall, and flooring and, while they were at it, put in a new kitchen sink. This was no ordinary reno project, though. The goal wasn’t to improve Verret’s home, but her health. And it was paid for by North Carolina’s Medicaid program, as part of a five-year, $650 million effort to address the social determinants of health.

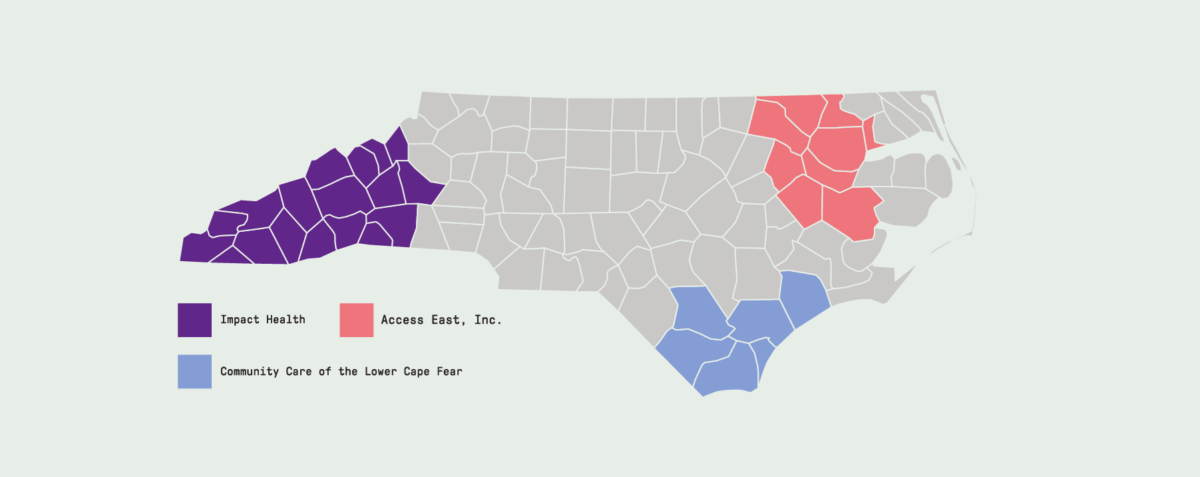

As part of the Healthy Opportunities Pilot, there are 52 organizations in western North Carolina providing a wide variety of services for Medicaid. The work on Verret’s home is covered because substandard housing has long been linked to chronic stress, respiratory ailments such as asthma, and an increased risk of death from disease, complication, accident, or exposure.

Dawn Verret, 61, in her home outside Asheville, North Carolina. Her bathroom renovation was covered under the Healthy Opportunities Pilot. The program also paid for a new kitchen sink.

Verret, 61, lost her job at the start of the pandemic, then was hospitalized in November 2020 for malnutrition and neuropathy. She ultimately qualified for Medicaid, the public health insurance program for low-income Americans. Her primary care visits and prescription medications were covered, but not the physical therapy she needed to regain her mobility. North Carolina, like many states, administers Medicaid through managed care organizations—Verret’s is provided through United Healthcare. Pneumonia put Verret back in the hospital in June 2022, and after she was released, United Healthcare sent a case worker to her mobile home in Candler, a rural community about a 20-minute drive from Asheville. “She saw my hallway, the condition of my bathroom and the condition I was living in, and said she knew about a program she thought I’d be a perfect referral for,” says Verret, who was expecting nothing of the sort. But the case worker referred Verret for the Healthy Opportunities Pilot, which covers up to $5,000 in home repairs annually. After a stint on the waiting list, the work started. Now that it’s completed, she says, “I really believe that I’m gonna be able to take care of myself and get stronger because I feel like I’m my best self.”

She chokes up and starts to cry. “I had not had a full shower since I was in the hospital. The one time I tried, I fell. You have no idea what being able to take a shower every day does to your self-esteem.”

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Spending thousands of dollars on a bathroom might not seem cost effective. But North Carolina’s Department of Health and Human Services views Healthy Opportunities as a long-term investment in what’s called “whole person care.” The idea is that behavioral and social factors also influence health outcomes. A healthier population will require fewer health care interventions—making sure someone with diabetes eats properly could mean less medication, fewer doctor visits and hospitalizations, and less risk of dialysis or amputation. The program grew out of a data paradox, says Elizabeth Tilson, the state health director and chief medical officer for the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS): 90 percent of U.S. health care spending goes to medical care, but 80 percent of what affects a person’s health happens outside of a medical setting. The DHHS calls it a commitment to “buying health, not just health care.”

The pilot program addresses four intertwined social needs that can subvert a person’s quality of life—food insecurity, housing instability, transportation challenges, and interpersonal violence and toxic stress. To qualify, Medicaid recipients living in the pilot regions must face at least one such social need and at least one qualifying health condition. North Carolina’s Medicaid project is notable for several reasons, says William K. Bleser, research director of health care transformation for social needs and health equity at the Margolis Center for Health Policy at Duke University. The project’s footprint is large (it covers roughly a third of the state); the project uses an evidence-based approach to services; and the project published a first-of-its-kind Medicaid social service fee schedule, which publicly defines and prices the program’s offerings. “A lot of states are watching North Carolina, and other states are even proposing to do something similar,” says Bleser.

They’re also watching because the program was developed while North Carolina was a holdout against Medicaid expansion—and billions of dollars in extra aid to the state—set in motion when the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010. When the Supreme Court in 2012 limited the federal government’s authority to mandate expansion, North Carolina was one of 20 states rejecting additional federal funding. At that time, its Republican governor, Pat McCrory, and the GOP-controlled general assembly argued that even if it didn’t cost more, it would expand the welfare state. McCrory was ousted after one term by Roy Cooper, a Democrat who centered his campaign around providing health care to an additional 600,000 North Carolinians through Medicaid expansion. One of Cooper’s first acts as governor was naming former Obama Administration Medicare and Medicaid official Mandy Cohen as North Carolina’s Secretary of Health and Human Services.

Cooper banked on Cohen’s high profile, political savvy, and intricate knowledge of the federal bureaucracy to help get expansion through the state legislature. By 2016, there was plenty of evidence nationally showing that Medicaid expansion had enhanced coverage, utilization, access to and quality of care, and health outcomes. And it had been a factor in improving economic measures for both states and providers. But the North Carolina legislature resisted expansion, instead focusing on what it labeled “Medicaid Transformation,” a shift from fee-for-service care to managed care provided by private health insurers. Cohen continued to make the case for expansion but also created a parallel program where Medicaid health insurance (and one day, Medicare and private insurers) would cover the social determinants of health. The DHHS applied for and received a Section 1115 federal waiver, which gives states additional flexibility to design and use “experimental, pilot, or demonstration projects deemed to better serve its Medicaid population.”

When Cohen stepped down in November 2021 (she is now director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), she was succeeded by her deputy, Kody Kinsley. He, along with Tilson, continued the rollout of Healthy Opportunities. The pilot program launched in March 2022, with food access as its first offering.

Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat (right), shakes hands with Phil Berger, Republican Senate majority leader, in March after Cooper signed the North Carolina's Medicaid expansion law.

Photo: Hannah Schoenbaum / AP Photo

North Carolina Health and Human Services Secretary Kody Kinsley speaks at a news conference.

Photo: Julia Wall / The News & Observer via AP Photos

Sonya Jones loads up her 2012 Honda Pilot with meats, proteins, and locally sourced fruits and vegetables, as she does four days a week. She’ll drive up to 100 miles today, delivering a week’s worth of food to people here in southern Appalachia. Some of them are in remote areas, but Ed and Dawn Hall are just five minutes from a supermarket. Both, though, suffer debilitating medical problems, making getting to the store a problem. Temperatures are near freezing this February day in Hendersonville, but Dawn Hall comes outside and greets Jones warmly. Hall looks over the food, asking questions like an excited child about the watermelon radishes, spaghetti squash, Swiss chard, and tangelos. “[Jones has] always got something different, and you get to choose whatever you want,” Hall tells me. “We have all kinds of health problems, so it’s important that we eat right.”

Jones is executive director of Caja Solidaria (the Solidarity Food Box), a nonprofit in Hendersonville launched initially as a food buying co-op during the pandemic to provide food and emotional support to people living in Henderson and Transylvania counties. Jones grew up in the region, has a PhD in nutrition, and spent 19 years at the University of South Carolina researching nutrition and food policy before becoming the coordinator at Henderson County’s Committee for Activity and Nutrition. She has long-standing relationships with many food-insecure families in the area.

Caja Solidaria was one of the first nonprofits to sign up with the Healthy Opportunities program, after being recruited by officials at Impact Health, a new agency established to coordinate the program in western North Carolina. “We weren’t interested in creating new nonprofits or new service lines,” says Laurie Stradley, Impact Health’s executive director. “Our goal was to understand what needs were already being met, and how those services could be provided and meet the fee schedule of the pilot.”

Bleser says North Carolina’s community care hub has a unique delivery model: using organizations already working in different regions of the state to create and manage the service delivery network. The approach strengthens the caregiving workforce and helps grassroots organizations and small nonprofits access planning funds to do things like expand staff, get new office space, or purchase a van for delivering services.

Impact Health recruited the only organization in the region that offers meals medically tailored to support specific health outcomes, the C2Life Foundation. C2Life is part of the pilot’s food-as-medicine initiative. Its gourmet freeze-and-heat vegetarian meals are microwavable for people who don’t have cooking facilities. Contracted service partners use the NC Care 360 database, a central portal with a detailed history of clients and benefits received, to connect enrollees with preventative nonmedical health services like transit passes, ride shares, home and auto repairs, and first month’s rent.

After the food services were up and running, Impact Health rolled out housing and transportation services. As of April 5, it also offers a program to counter interpersonal violence. This aspect was initially delayed when the North Carolina Coalition Against Domestic Violence raised concerns that including care recipients in the database could put them at risk. Those issues have now been resolved, meaning Healthy Opportunities recipients can receive services like peer support, safety planning, and de-escalation training.

The pilot experienced significant challenges with the enrollment and referral processes when it launched. Because the Section 1115 federal waiver requires all services be pre-approved, care managers had to identify eligible people, determine which services they needed, and then get approval from the health plan to enroll them. Having just one route of entry created a bottleneck and a backlog.

So Impact Health’s Stradley and staff from the network leads for the other two pilot areas worked with the Department of Health and Human Services to implement the “No Wrong Door” approach. No Wrong Door allows service referrals to come from health service organizations, health care providers, and Medicaid recipients themselves. Most enrollees now receive services within two days.

Pilot Areas

As of July, Healthy Opportunities has served nearly 13,000 Medicaid members and delivered more than 111,000 services to enrollees, relatively modest numbers, considering there are more than 578,000 Medicaid recipients in the pilot’s regions. Tilson, the DHHS state health director, says Healthy Opportunities has moved deliberately. “This was a totally new way to deliver services, so we intentionally did a bit of a slow rollout as we’re trying to get all the players to work together,” she says.

Pamela Peak found out about the program from her hospital bed, even though she works for one of its participating organizations. Peak had complications from gastric bypass surgery and spent two months in the hospital. She was stunned when a Healthy Opportunities coordinator let her know that her obesity, back-to-back hospitalizations, and food insecurity qualified her for the program. “She offered me food and a variety of services that I didn’t know existed,” says Peak.

Now at work as a care navigator for Impact Health, Peak is also a kind of Health Opportunities recruiter. She’s especially spreading the word in the Black community in this region—North Carolina’s least diverse, and one where some groups have had negative experiences with the health care system or have felt excluded from service programs. Impact Health’s Stradley acknowledges there is more work to do, saying Black residents have complained that Healthy Opportunities doesn’t recognize their specific needs or include providers of color. The area’s growing Latino population has also proven reluctant to register, which Stradley says stems from many of them being in gray areas of citizenship and eligibility. Despite such issues, Bleser, the Duke researcher, says that “to get from zero to where it is now is significant.”

Pamela Peak stands outside her home in Flat Rock, North Carolina. Peak did not realize the Healthy Opportunities Pilot program existed when she needed it. She has become a champion for the program, especially in the Black community in her area.

The state provided funding to build capacity for three years, after which the nonprofit must get enough people in the door to sustain itself with a fee-for-service model. It may help long-term sustainability that the pool of potential enrollees just got bigger.

Driven by factors like extra federal incentives, the precarious financial condition of many rural hospitals, and the end of a COVID-19 pandemic provision that will remove millions of people from the Medicaid rolls, North Carolina became the 40th state to expand Medicaid on March 28, 2023—and the first of the holdouts to do it legislatively versus by ballot initiative since 2018. Expanding Medicaid will make more people in the three pilot regions eligible for the program.

Whether the program continues after the pilot stage will be determined in large part by the program’s costs versus its benefits. Stradley says looking for dollar-for-dollar savings misses the point: The savings won’t be immediate but will show up generationally. Patience will be rewarded, predicts one observer. “In the medium to long term, helping to prevent serious disease will be more than worth the initial investments,” says Lawrence Gostin, director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Center for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University. “Treatments for a wide range of preventable diseases can be hugely expensive. If we can prevent, or even delay, the onset of disease, it is money very well spent.”

Success will be measured by metrics such as the number of emergency room visits and effects of disease management in the first five years using baseline data established by researchers at the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dawn Verret is already convinced of the program’s value—it changed her life. But because she has now been disabled for more than 24 months, she was automatically moved from Medicaid to Medicare and no longer has access to benefits for social determinants of health. This shift has her a little concerned. “I don’t know what I think about that,” she says. “United Healthcare really took care of me.”

Top image: As part of North Carolina Medicaid’s Healthy Opportunities Pilot, a person receives a fresh food delivery from Caja Solidaria, a nonprofit dedicated to healthier diets.