Newsletter

HPH Weekly: Can the sober curious trend change U.S. alcohol consumption?

This edition of Harvard Public Health Weekly was sent to our subscribers on Jan. 4, 2024. If you don’t already receive the newsletter, subscribe here. To see more past newsletters, visit our archives.

Can the sober curious trend change U.S. alcohol consumption?

The holidays are over and the season’s iconic indulgences of frosted cookies and hot toddies have given way to the traditional temperance of Dry January (or Damp January for those interested in moderation over abstinence). But for more and more younger Americans, avoiding alcohol is not just a seasonal thing.

Our reporter, Sandra Lamb, took a closer look at these new consumption patterns. She found “no-alcohol” bars popping up from New York City to Milwaukee—and new moves to tax take-home alcohol, despite resistance from the alcohol lobby. While policy measures encouraging people to drink less are still piecemeal, and regular bars still vastly outnumber no-alcohol ones, experts say any little bit helps.

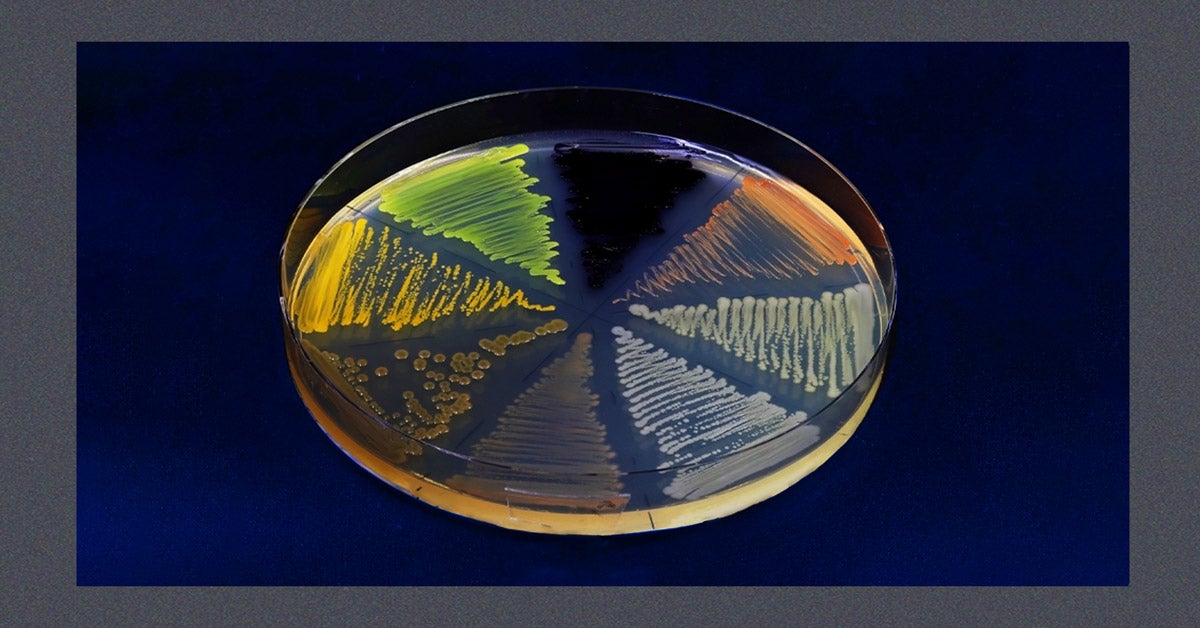

Superbugs thrive in the ruins of war

It’s long been known that “superbugs”—antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) bacteria—flourish in war zones. Yet we’ve made little progress toward containing drug-resistant infections in wartime, writes Henry Skinner, CEO of the AMR Action Fund. Instead, the world relies on hand-washing, good antibiotics stewardship, and piecemeal improvements in surveillance. “These efforts have impact and are commendable,” he writes, “but it is like trying to control a forest fire with a garden hose.”

Skinner calls for governments to invest where the pharmaceutical industry won’t. Only then, he argues, can we take meaningful steps toward addressing a problem of this scale.

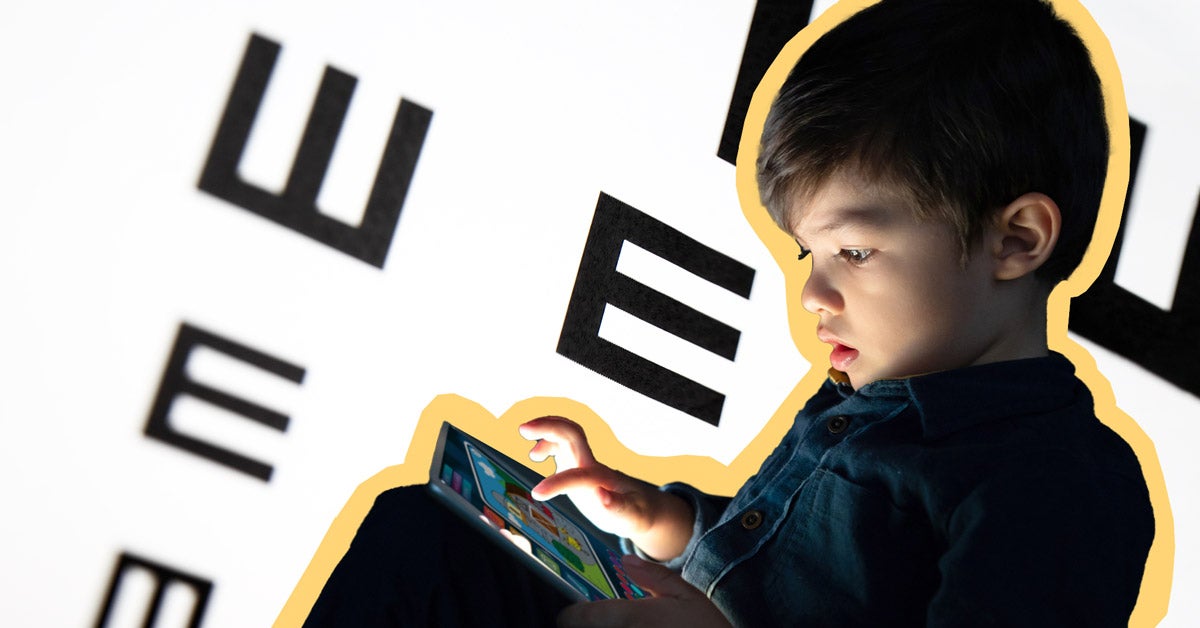

Myopia in children: does staring at a screen damage eyesight?

By 2050, nearly one billion people will be severely nearsighted, writes reporter Alex Smith. Nearsightedness, or myopia, mostly means a lifelong dependence on glasses or contacts, but sometimes it leads to complications like retinal tearing, glaucoma, or macular degeneration, especially later in life. No one knows exactly why myopia is becoming so prevalent, but getting quality care for the condition can be challenging, especially for low-income families. Myopia treatments are few, and vision insurance remains rare.

What we’re reading this week

- America has a life expectancy crisis. But it’s not a political priority. | The Washington Post

- How to be a healthier drinker | TIME

- Several countries made progress in disease elimination in 2023 | NPR

- Can family doctors deliver rural America from its maternal health crisis? | KFF Health News

- Medicare is about to add hundreds of thousands more mental health providers | Axios

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.