Feature

Fighting nearsightedness in the age of the screen

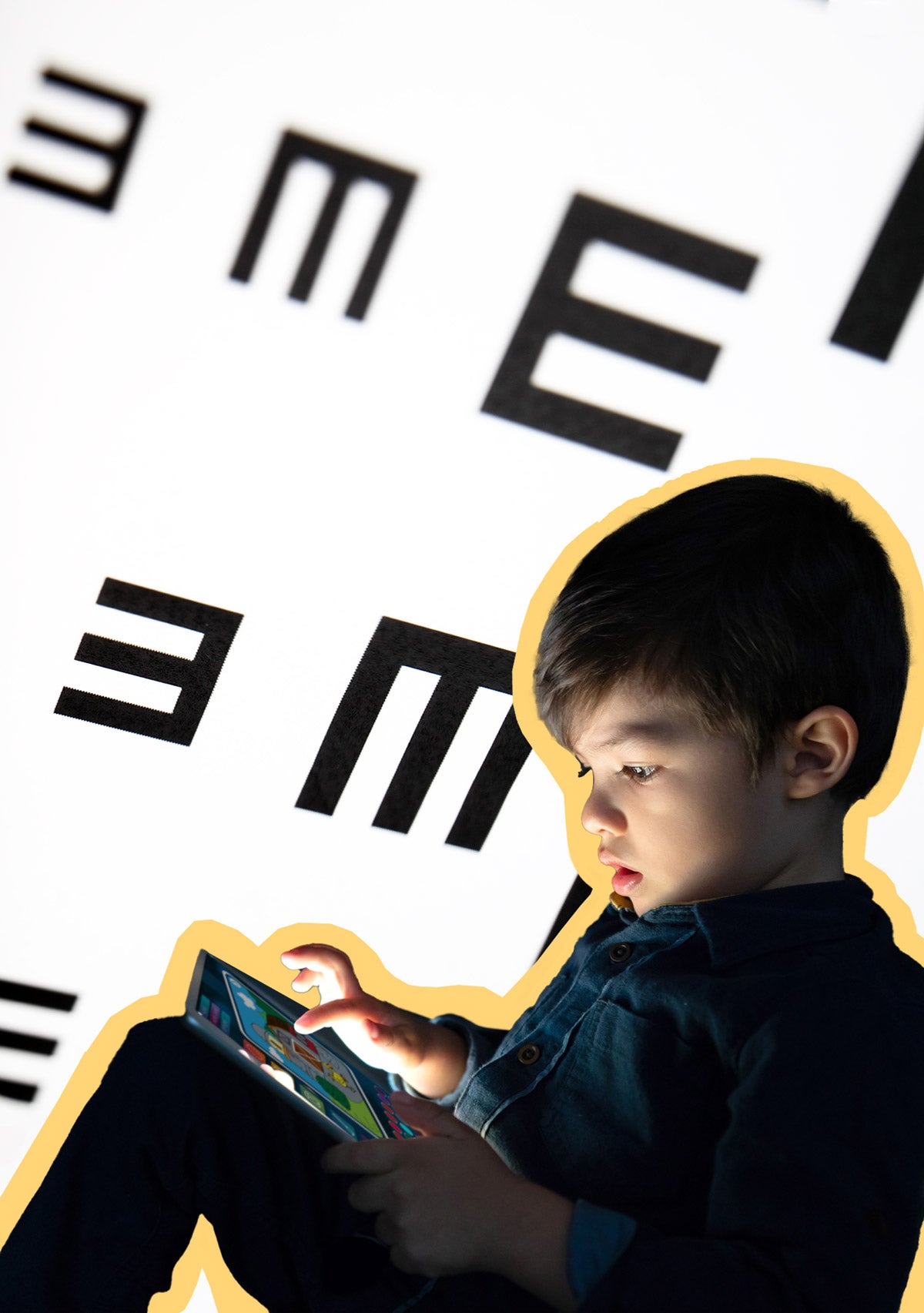

When my seven-year-old son, Ari, read the letters on the exam chart in the eye doctor’s office, he got one letter after another wrong. I worried: Was it too dark in the exam room? Was my son’s grasp of the alphabet not as solid as I thought?

The truth was, of course, that Ari is nearsighted; he’d probably need glasses before long. “We’re seeing a surge in myopia in kids,” his eye doctor told us, “particularly since the start of pandemic.” The doctor said screens were a likely culprit, and my heart sank. We had caved on our no-screens policy during the pandemic. Had the extended staring contests with PBS Kids permanently altered my son’s eyeballs?

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Myopia is an unusual elongated growth pattern of the eyeball, which usually begins in childhood and is likely caused by genetics and environment. Sometimes, the condition can do great damage later in life. Myopia is associated with higher rates of glaucoma, cataracts, retinal tears, and macular degeneration—all diseases which can rob someone of their sight entirely. Those risks appear much more significant for people whose childhood diagnosis progresses into severe or “high” myopia. Nearly 10 percent of the world’s population, or close to one billion people, will have high myopia by 2050, according to estimates.

For most children, though, myopia only leads to nearsightedness and a lifelong need for glasses or other vision correction. In children with myopia, vision generally stabilizes by age 20, although higher risks of blinding eye disease continue throughout one’s life.

Myopia rates have been on the rise since well before the dawn of smart devices. They jumped from 25 percent in the U.S. early 1970s to about 42 percent around the turn of the millennium, according to one study. Estimates suggest half of the world will be nearsighted by 2050. Some parts of the world have already far surpassed that milestone; in some East Asian countries, myopia rates have climbed as high as 80 to 90 percent.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, multiple studies have shown, myopia rates increased significantly among children. While more screen time has been suspected as a culprit, most of the studies did not specifically investigate screen time during lockdowns. Despite the ubiquity of smartphones—84 percent teenagers in the U.S. own one, according to a 2019 study—experts remain unsure about exactly what they do to our eyes.

“Near work,” such as reading, has long been associated with nearsightedness— although it’s still not entirely clear whether lots of reading contributes to myopia, or if people who can’t see distances well gravitate toward books. “It’s sort of a chicken and egg situation,” says Mark Rosenfield, professor at the State University of New York College of Optometry. “What came first? The myopia or the reading?”

Rosenfield says that while screens are known to cause eye strain and may be contributing to myopia, other factors, like extended time spent in dark indoor settings, likely deserve at least some of the blame. “But of course, it could be a combination of the two,” he says. Stress, he adds, may play a role as well.

The relatively new field of myopia management has been growing worldwide, although many other countries offer patients more treatment options than are available in the United States, where approvals lag behind.

Myopia control tools include orthokeratology, or “ortho-k”, a more rigid lens worn at night, and atropine, an eye drop. Atropine was used to treat myopia as far back as 1868, but it fell out of favor due to problematic side effects; more recently, lower doses of atropine, which is widely used in East Asia, have proven more tolerable. But the Food and Drug Administration found the substance to be ineffective against myopia in recent trials. (This surprised many optometrists, who questioned the trial’s design.) Myopia-control glasses are also used in other countries, providing families with a more kid-friendly treatment than contacts, but the glasses have yet to be approved for use in the U.S.

One promising new treatment that is taking off in the U.S. is specialized contact lenses to help control myopia. At a clinic run by the New England College of Optometry in Brookline, Massachusetts, Fuensanta Vera-Diaz pulls back the foil from a single contact lens package and fishes out the floppy sliver of clear plastic. She lifts the MiSight myopia control lens to the light on her fingertips. It looks slightly smaller than a standard adult contact lens, but these lenses and similar technology have changed the conversations she has with families. The myopia control daily lenses are designed not only to correct vision, but unlike traditional contacts or glasses, they can also slow that unusual growth progression, preventing severe myopia and other risks.

“It’s definitely very uplifting—the fact that we can provide hope for these children,” Vera-Diaz says. “We definitely can do something, whereas we couldn’t 15 years ago.”

In the U.S., insurance is an obstacle to accessing innovative treatments like myopia-arresting lenses, and more generally to quality myopia care. Vision care is not included in most health insurance for U.S. adults; the coverage typically costs extra and is optional. Even for children, whose insurance is obligated to pay for eye care, myopia treatment is regularly regarded as experimental by insurers, who may either exclude it from coverage entirely or require hefty out-of-pocket costs. Many optometrists who treat myopia don’t accept Medicaid due to its low payments, which creates more hurdles for low-income families, says Sandra Block, president of the World Council of Optometry.

Though insurance policies and other barriers mean that kids’ myopia treatments remain out of reach for many families like mine, scientists say one of the most effective strategies for stopping the disease is more readily available: Going outside. Though researchers still aren’t exactly clear on how sunlight and open spaces might affect the eyes, they agree that simply spending time outdoors can prevent myopia from developing. “The best thing is sunlight exposure,” Rosenfield says. “I recommend parents should try and get their kids outside—playing outside. It’s a win-win situation.”

Source images: ngkaki / iStock, andresr / iStock