Ideas

Fighting back against climate change, block by block

Sensing Crop Health

David Kramer, a biology professor at Michigan State University, wanted to know how plants grow and flourish in the real world, outside highly controlled lab experiments. Climate change “is happening so fast that our crop breeders don’t have a chance to catch up,” he says. Measurement tools existed, but he found them expensive, difficult to use, and designed primarily for big companies growing soybeans, wheat, or corn.

So his lab developed MultispeQ, a handheld sensor that can measure plant health and productivity, including energy use, water loss, chloroplast damage, and efficiency of photosynthesis. These data, Kramer says, can help predict crop yield and alert farmers to disease or nutrient deficiency, a problem that is projected to worsen as atmospheric CO2 levels rise.

MultispeQ's sensor in action

Photo: Courtesy of MultispeQ

MultispeQ, which is sold for about $1,700 per unit by PhotosynQ, a company Kramer co-founded, works in tandem with a cellphone app the user can program to assess various metrics of crop health. The app, in turn, feeds those data into the PhotosynQ Community Open Platform, a free, open-access database with more than 6,600 users worldwide, ranging from small farmers to seed companies to research universities in 30 countries. The platform is being used to collect and analyze data on wild turnips in Australia, black-eyed peas in Zambia, and strawberries in Chile.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

The implications for health are both direct and indirect: Research using the data could help prevent food insecurity and malnutrition caused by crop loss and nutrient deficiency. The PhotosynQ platform can also guide farmers’ use of fertilizer, which can run into waterways and cause toxic algal bloom, killing fish, contaminating seafood, and polluting drinking sources. Limiting the use of pesticides could also reduce harm to farmworkers and their families.

Kramer says PhotosynQ isn’t directly involved in many of the projects that use its platform. The goal, he says, is to “put the tools into the people’s hands, giving them the ability to interpret the data that they get in a meaningful way.” He adds: “This kind of open, global science is what we need to address these big problems.”

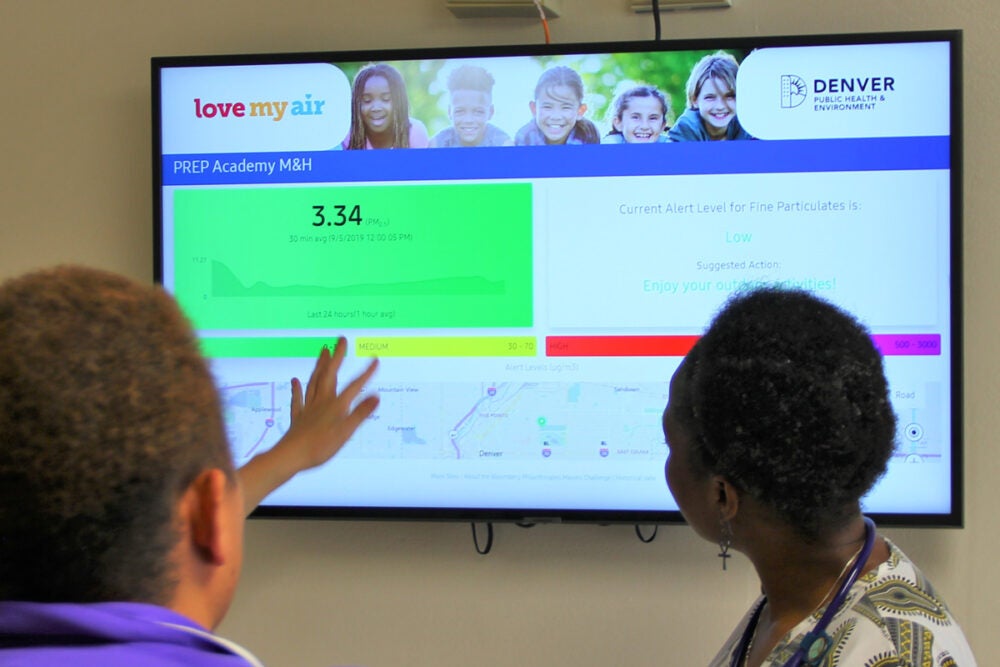

Mile-High Eye on Asthma

Photo: Courtesy of City and County of Denver

Air pollution is a known trigger for asthma attacks, especially in children. Denver’s poor air quality—it’s the nation’s eighth worst for ozone—prompted the city’s Department of Public Health and Environment to launch the Love My Air program in 2018. The department placed sensors measuring the levels of fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) outside three dozen public schools. It has sought to help kids prevent and manage asthma symptoms as ozone levels hit record highs in 2021 and particulate matter soared, in part due to wildfire smoke.

Asthma affects 10 percent of the 89,000 students in Denver public schools, with rates exceeding 25 percent at several schools, according to district data for the fall of 2021. Love My Air displays pollution data on a health department website and in school hallways, where TV screens offer a 15-minute rolling average of air quality. The program also offers school nurses a toolkit for educating and treating children with asthma. And classroom lessons using the data are offered to teachers at all grade levels.

The air quality data supports a district campaign that aims to persuade bus drivers and parents to stop idling vehicles outside schools, says Michael Ogletree, who leads the Love My Air initiative. His team is also working on sharing the data in a free app.

It’s too soon to say how the program has affected asthma flare-ups, but the idea may catch on: Love My Air, funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies, is in talks with other city governments about replicating the program and sharing data, Ogletree says.

Flood Predictor

Tomorrow.io, a Boston-based weather-forecasting company, launched a Flood Risk Index in September 2021 aimed at helping cities and companies prepare for severe floods.

Photo: Courtesy of Tomorrow.io

Heavy rainfall and floods are happening more frequently, bringing with them direct health impacts such as drownings, as well as potential surges in infectious diseases by contaminating drinking sources or seafood with toxic runoff or algal blooms. With the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change saying more intense and frequent storms are “very likely,” precision flood projections would be a clear boon.

Tomorrow.io, a Boston-based weather-forecasting company, launched a Flood Risk Index in September 2021 aimed at helping cities and companies prepare for severe floods. The index uses a mix of proprietary and existing weather models, incorporating 40 years of runoff and streamflow data, to predict severe flooding up to five days in advance.

The Flood Risk Index feeds into the company’s Weather Intelligence Platform, which is used by hundreds of businesses and municipalities around the world, says Dan Stillman, a Tomorrow.io spokesman. Customers identify weather thresholds—for example, two inches of rain in one hour—that would trigger emergencies in their geographic area, and the platform alerts them when those scenarios are forecast.

Better forecasts could help cities mobilize earlier for impending floods, and Stillman notes they could also help health systems avoid having to cancel elective appointments due to false alarms.

By 2024, the company plans to launch about 30 satellites into space, each the size of a mini-fridge and equipped with radar that measures rainfall from above. “Radar is really the optimal way to measure rainfall,” says J. Marshall Shepherd, former deputy project scientist for NASA’s Global Precipitation Measurement mission and a Tomorrow.io consultant. He says these satellites would significantly improve upon the coverage that NASA provides from space and fill gaps in ground-based storm radar coverage both in the U.S. and in developing countries.