Essay

To protect gender-affirming care, we must learn from trans history

The current culture war against transgender people and gender-affirming care in the United States has been fierce. Nineteen states have passed laws restricting gender-affirming hormone therapy or transition surgery for minors, 16 of them in just the past few months, and several more are considering similar legislation. Lawmakers in Florida and Missouri have also sought to cut off adults’ access to care, and other states may follow.

The moral panic and hate-fueled backlash against gender-affirming care and trans people may seem to have erupted from nowhere. But it has deep historical precedent. In fact, this contemporary wave of restrictions echoes the backlash experienced by pioneers of gender-affirming care during World War II in Germany, and again in the 1970s right here in the U.S.

As we consider how best to respond to the anti-trans wave, it’s important we reflect on that history—and seek to learn from it.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

First, some background: Gender-affirming care is the treatment gold standard for gender dysphoria. It has been endorsed by every major medical association in the U.S., including the American Medical Association, World Professional Association for Transgender Health, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Psychological Association, and the Endocrine Society.

Transitioning can be as simple as changing gender expression by adopting a new hairstyle, name, pronoun, or style of clothing. Counseling is often an element of treatment. Some transgender patients may also receive medical intervention in the form of hormone replacement therapy or surgery. These standards have been established and supported by decades of scientific research.

The field’s earliest roots date back to the 1920s, when physician Magnus Hirschfeld and other physicians conducted the first formal studies and treatment of gender dysphoria in Germany.

Born in 1868, Hirschfeld dedicated his life to understanding human sexuality and advocated for the rights of marginalized communities, including the LGBTQ+ population. His work was groundbreaking for the time, and offered a new perspective on gender and sexuality that challenged existing societal norms.

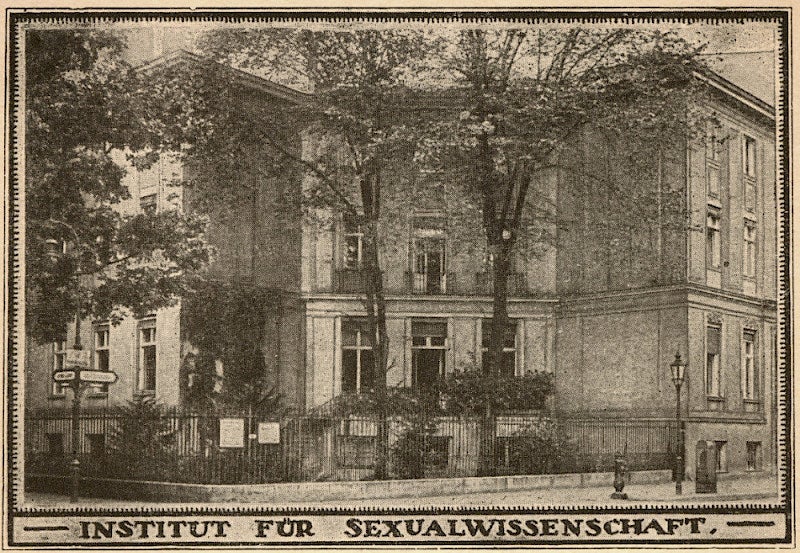

Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld founded the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft in 1919, and pioneered early research on gender-affirming care.

The Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, often translated as the Institute for the Science of Sexuality, opened in July 1919 in Berlin-Tiergarten, Germany.

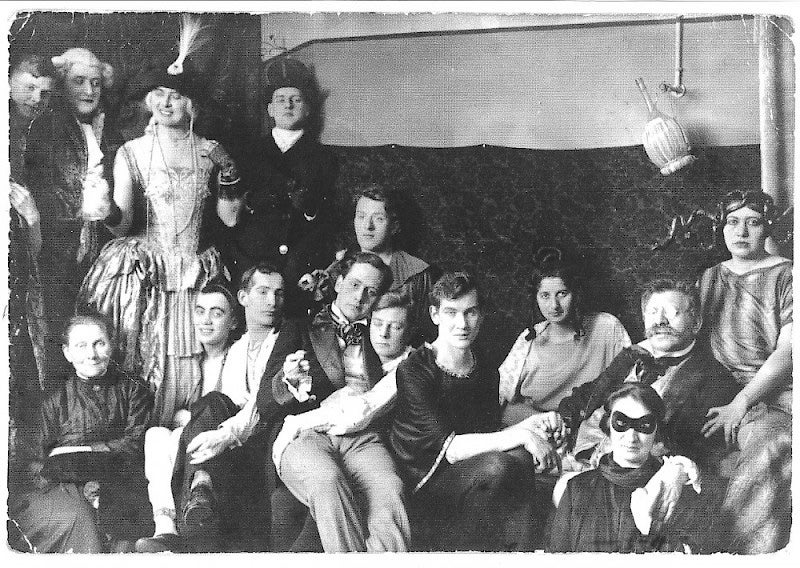

Members of the Institute pose for a photo.

Hirschfeld and colleagues at his institute collected extensive data on transgender people through interviews, surveys, and clinical observations, providing the foundation for modern gender-affirming care. They were among the first to recognize that gender identity was distinct from sexual orientation, and that transgender individuals required unique support and care. Hirschfeld is also credited with coining the term “transvestite” in 1910, which was later replaced by the more modern term “transgender.”

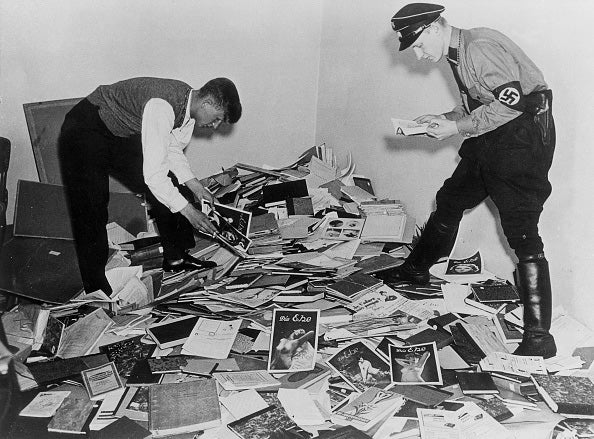

In an echo of today’s culture wars, Hirschfeld and the institute faced considerable opposition from conservative elements in society, accused of promoting “degeneracy” and undermining traditional family values. The institute was frequently targeted by the rising Nazi party, which viewed Hirschfeld’s work as a threat to traditional German values and targeted gay and trans individuals as part of their larger campaign against so-called “un-German” ideas. In May 1933, the Nazis raided Hirschfeld’s institute, confiscating and destroying invaluable research material. These research documents were burned in a public square, alongside thousands of other books, including a book by Jewish poet Heinrich Heine that featured the famous quote “where they burn books, they ultimately burn people.” The first trans woman to undergo vaginoplasty, Dora Richter, is believed to have been murdered during the raid.

Once the Nazis gained power, their persecution of transgender individuals extended beyond the destruction of Hirschfeld’s institute. The Nazis targeted transgender people, with many being arrested, imprisoned, and sent to concentration camps. Hirschfeld’s work, once a beacon of hope and progress for transgender individuals, was effectively silenced during this dark period in German history.

In May 1933, students of the National-Socialist German Students Union, a division of the Nazi party, burned thousands of 'un-German and decadent' books. The picture shows the confiscation of the Institute for the Science of Sexuality library.

It may be tempting to see the Nazi period as an anomaly, but it has clear parallels to today’s efforts to demonize and dehumanize the LGBTQ+ community and deny the very existence of trans people. Such rhetoric has consequences: It enflames hatred and emboldens extremists to commit acts of violence. For trans individuals, these are dangerous times, indeed.

It’s important to remember, however, that the trans community has at other times made strides in gaining access to care. In the years following World War II, Hirschfeld’s ideas became influential, inspiring new generations of researchers and advocates. In the U.S., the post-war period saw a wave of new researchers and medical professionals exploring the unique needs of transgender individuals.

It may be tempting to see the Nazi period as an anomaly, but it has clear parallels to today’s efforts to demonize and dehumanize the LGBTQ+ community and deny the very existence of trans people.

The pioneering Johns Hopkins Gender Clinic, which opened in 1966, represented a huge step forward. It was among the first in the U.S. to provide comprehensive care for transgender individuals, including counseling, hormone therapy, and gender-affirming surgeries. Among its innovations was the “Real-Life Test,” which required patients to live in their preferred gender role for an extended period of time before being considered for gender-affirming surgery. The clinic’s work also emphasized the importance of providing comprehensive care for transgender individuals, including psychological counseling and support alongside medical treatments.

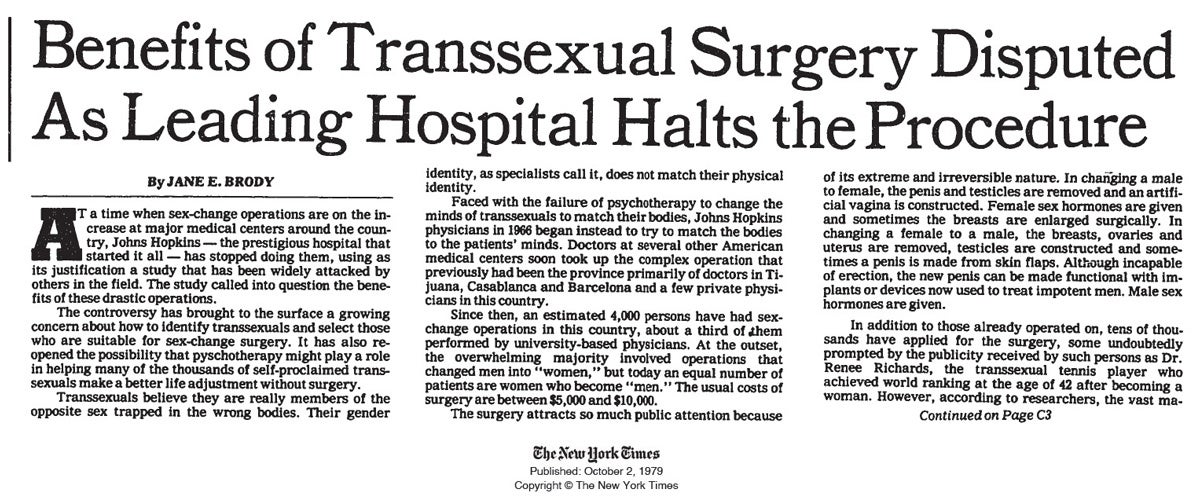

Progress hit a wall in 1979 with the publication of Janice Raymond’s transphobic tome, “The Transsexual Empire,” an exclusionary feminist argument against the existence of trans people. Soon after, Dr. Paul McHugh, the recently appointed director of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins, decided to close the gender clinic. McHugh, who held conservative views on matters related to gender and sexuality, argued the clinic was promoting mental illness by encouraging individuals to transition. Coverage from the New York Times about the closing of the clinic in 1979 is eerily similar to today’s media coverage about gender-affirming care, complete with critics raising concerns about efficacy and suggesting some patients came to “regret” their decisions.

New York Times article, October 2, 1979.

In the ensuing years, the backlash accelerated. In the early 1980s, President Ronald Reagan’s Department of Health and Human Services determined that gender-affirming care was experimental and therefore not covered by federal insurance programs such as Medicaid and Medicare. Most private insurance companies followed suit. This decision had far-reaching implications for transgender individuals, as it significantly limited their access to medically necessary treatments, including both hormone therapy and surgeries, and reinforced the stigma surrounding transgender health care. It also created a catch-22—medical care could not be covered because it was “experimental”—but research evaluating treatment efficacy could not be conducted either because of the lack of federal funding.

As the result of tireless activism by the transgender community and others, there has been a resurgence in access to transgender health care in recent years. The Affordable Care Act of 2010 expanded protections for gender-affirming care and the federal government removed the “experimental” designation in 2016. Better insurance coverage led to more clinics opening or expanding. Advances in medical knowledge improved the quality of care. And until the current vicious wave of discrimination, attitudes towards gender-affirming care had been starting to shift, both within the medical community and in society at large.

While history does not repeat itself precisely, it certainly rhymes. As we enter another period of intense scrutiny and reactionary backlash against the LGBTQ+ community, it is crucial to learn from this history. Studying the parallels between our past and present can help us ensure we do not make the same mistakes once again. We should continue advocating for the rights and needs of transgender individuals and continue pushing back against oppressive laws.

By recognizing the importance of gender-affirming care and working to dismantle the barriers that limit access, we can help ensure that all transgender individuals have the opportunity to live their lives as fully and authentically as possible.

Photo illustration source images, L-R: ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images, Vincent Maggiora/San Francisco Chronicle via AP Photos, Julia Weeks / AP Photo.

Magnus Hirshcfeld Institute images: Courtesy of the Archive of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society eV, Berlin.

Burning materials image: ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images.

Newspaper clipping: The New York Times, October 2, 1979.