Feature

How Indigenous Knowledge may shape the future of U.S. policy

Over the last decade, the federal government has recognized Indigenous Knowledge as an asset in efforts to combat climate change and environmental degradation. The Biden administration has gone a step further, instructing federal agencies to integrate indigenous practices and teachings into all kinds of policies — including those addressing public health. Agencies are due to report on their progress soon.

The move is “setting a tone that tribes should be treated with respect, as sovereign nations,” said Chuck Hoskin Jr., principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, the largest tribe in the U.S. with 440,000 enrolled citizens.

The federal guidance, issued in late 2022, calls on agencies to draw on indigenous “observations, oral and written knowledge, innovations, practices, and beliefs” in their policies and programs. Public health agencies including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Institutes of Health were part of an interagency working group that drafted the guidance document. And indigenous researchers say public health could be a particularly important frontier for integrating tribal knowledge.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

“Success cannot be defined solely in terms of how this will benefit Native people,” said Angela Gonzales, an associate professor at Arizona State University and enrolled citizen of the Hopi Nation. “We also need to ensure Indigenous Knowledge is equitably understood and infused throughout the entire health care delivery and research process.”

Diabetes is a prime example, says Valarie Blue Bird Jernigan, the executive director at the Center for Indigenous Health Research and Policy at Oklahoma State University and a citizen of the Choctaw tribe.

The high prevalence of diabetes among indigenous people reflects the consequences of forced removal from their land, underfunded healthcare, and inadequate access to healthy foods over many generations, says Blue Bird Jernigan. She explains that many tribal members, including herself, grew up consuming commodity packages, or government-provided foods that are typically heavily processed with low nutritional value. Tribal health systems have focused on treating diabetes once it arises, rather than prevention efforts, perpetuating the belief that diabetes is inevitable.

Blue Bird Jernigan saw an opportunity to change this. In 2018, she partnered with the Osage Nation of Oklahoma to implement a nutrition curriculum across nine tribally-owned and operated preschools to educate kids about vegetables and their parents about traditional food cultivation and preparation practices. The program also includes hands-on activities at Bird Creek Farm, a “sustainable community agricultural resource” for Osage youth, elders, and future generations, with the goal of promoting indigenous food sovereignty and reducing dependence on government-provided food.

By involving children and parents, Blue Bird Jernigan says her approach appeals to local values that emphasize a community’s responsibility to consider sustainability and diabetes prevention “across multiple generations.” This differs from standard interventions, which prioritize individual goals such as weight loss. Now, as the first tribal member to join the federal Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, Blue Bird Jernigan says she’ll bring her experience to developing national dietary guidance that is inclusive of diverse racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and cultural backgrounds.

“As a community-engaged researcher I value lived experiential knowledge as much as scientific knowledge,” Blue Bird Jernigan said.

The COVID-19 pandemic also highlighted the effectiveness of Indigenous Knowledge in controlling infectious disease. Abigail Echo-Hawk, director of the Urban Indian Health Institute and a citizen of the Pawnee Nation, says “the most successful COVID-19 interventions were done by the tribal communities themselves,” with many tribes implementing quarantine measures weeks before state agencies issued similar directives. These initiatives were grounded in Indigenous Knowledge of how past epidemics, such as Hepatitis A and tuberculosis, disproportionately affected tribal communities.

“There’s a phrase we use in our community today: ‘I am the wildest dreams of my ancestors.’”

Abigail Echo-Hawk, director of the Urban Indian Health Institute and citizen of the Pawnee Nation

“Within our cultural value systems, it is our duty as tribal people to care for and ensure the health and well-being of our children and our elders,” Echo-Hawk explained. “In the past, tribes have been most successful at curbing infectious disease spread when they leaned on those values, and the COVID-19 pandemic was no exception.”

The Cherokee Nation’s pandemic response is one example. As COVID-19 cases surged across the U.S., Cherokee officials acted swiftly to protect tribal elders. Hoskin Jr., the tribe’s chief, declared a state of emergency in March 2020, requesting that all citizens help shield the tribe’s elders. “Putting elders first is simply our way of life,” Hoskin Jr. wrote in one public statement. Tribal officials also masked a statue of Cherokee statesman Sequoyah as a symbolic tribute to their longstanding tradition of protecting others in the community. Hoskin Jr. says these appeals were crucial in securing public buy-in for the tribe’s aggressive masking and social distancing policies.

State and federal vaccination programs could take cues from tribal health programs as well, says Echo-Hawk. Throughout much of the pandemic, indigenous health providers led the nation in COVID-19 vaccine distribution, which Echo-Hawk attributes to tribal sovereignty and the use of community-based approaches to address vaccine skepticism.

Indeed, in the first-ever national survey on attitudes toward vaccines among American Indians and Alaskan Natives, her team at the Urban Indian Health Institute found that 75 percent of indigenous people were willing to be vaccinated. That number was just 63 percent amongst the broader American public. The survey found the willingness to take the vaccine stems from a deeply embedded culture of responsibility towards protecting elders and other vulnerable members of the community.

Vaccination campaigns that underscored indigenous communities’ resilience and resistance against historical injustices also resonated, says Echo-Hawk. “There’s a phrase we use in our community today: ‘I am the wildest dreams of my ancestors.’”

Indigenous leaders hope the momentum to broadly incorporate indigenous expertise into federal governance will last beyond the current administration. “When a new presidential administration comes in, irrespective of the party, it’s almost like you’re starting over. And we don’t need to start over given the progress embodied in this recent document,” Hoskin Jr. said. He suggests that establishing advisory bodies that provide continuity between administrations could help stay the course of the progress made thus far.

Echo-Hawk notes that previous White House initiatives to integrate Indigenous Knowledge into federal policies and decision-making haven’t always stuck. Under President Barack Obama the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration created a framework that recognizes historical trauma as the underpinning of behavioral health issues in Indian country. For instance, the Tribal Opioid Response Grant, one of three exclusively meant for tribes, combines cultural practices like sweat lodges, talking circles, traditional healers, drum ceremonies, and powwow gatherings with Western medicine and psychology like cognitive behavioral therapy.

“It was very successful. But when we went from the Obama administration to the Trump administration, there was less focus on upholding that plan,” Echo-Hawk said.

Gonzales, the associate professor at Arizona State, said she was encouraged that the Biden administration recognized “the uniqueness of indigenous people” that helped distinguish First Nations from other racial and ethnic groups and said the directive could be “transformational” if it maintains momentum. “I was really glad that this special acknowledgement didn’t just get collapsed into the bigger DEI movement,” she added.

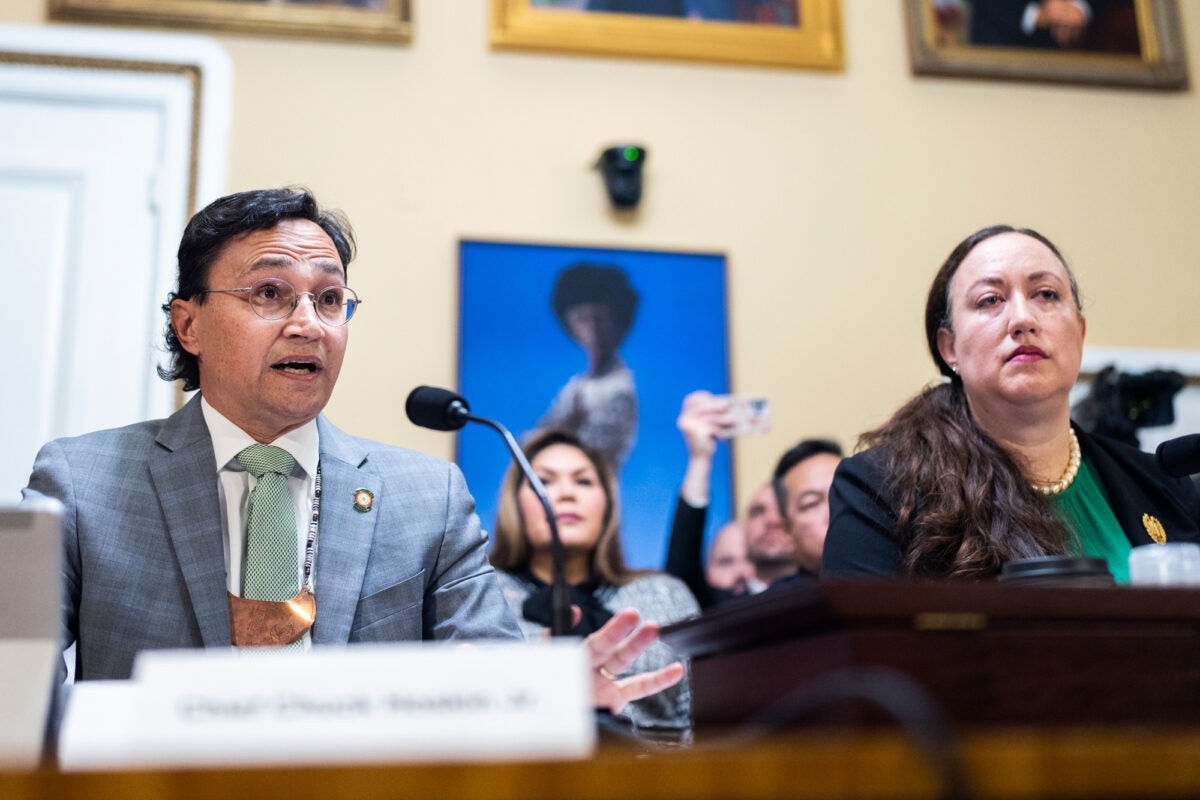

Top image: Cherokee Nation Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. (left), and Mainon Schwartz, attorney at the Congressional Research Services (right), speak during a House Rules Committee hearing on legal and procedural factors related to seating a Cherokee Nation delegate in the U.S. House of Representatives in November 2022. Credit: Tom Williams / CQ Roll Call via AP Images