Opinion

Tracking superbugs in the wake of war

Last year, a 50-year-old Ukrainian soldier suffered horrific injuries after his vehicle was hit by munitions and burst into flames. In need of specialized care, he was transported to a U.S. military hospital in Germany, where clinicians were alarmed to discover he was carrying six different types of drug-resistant bacteria. One of them was a strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae resistant to every antibiotic that researchers had tested against it.

Of all the ripple effects associated with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, accelerating the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria might prove the most consequential for global public health. These “superbugs” flourish in the unsanitary conditions of war and can quickly travel from bombed-out barracks to hospitals and civilian populations thousands of miles away from the frontlines.

The risk is high. Yet very little progress has been made in recent decades toward improving the technologies underpinning how we detect, track, and treat antibiotic-resistant infections.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

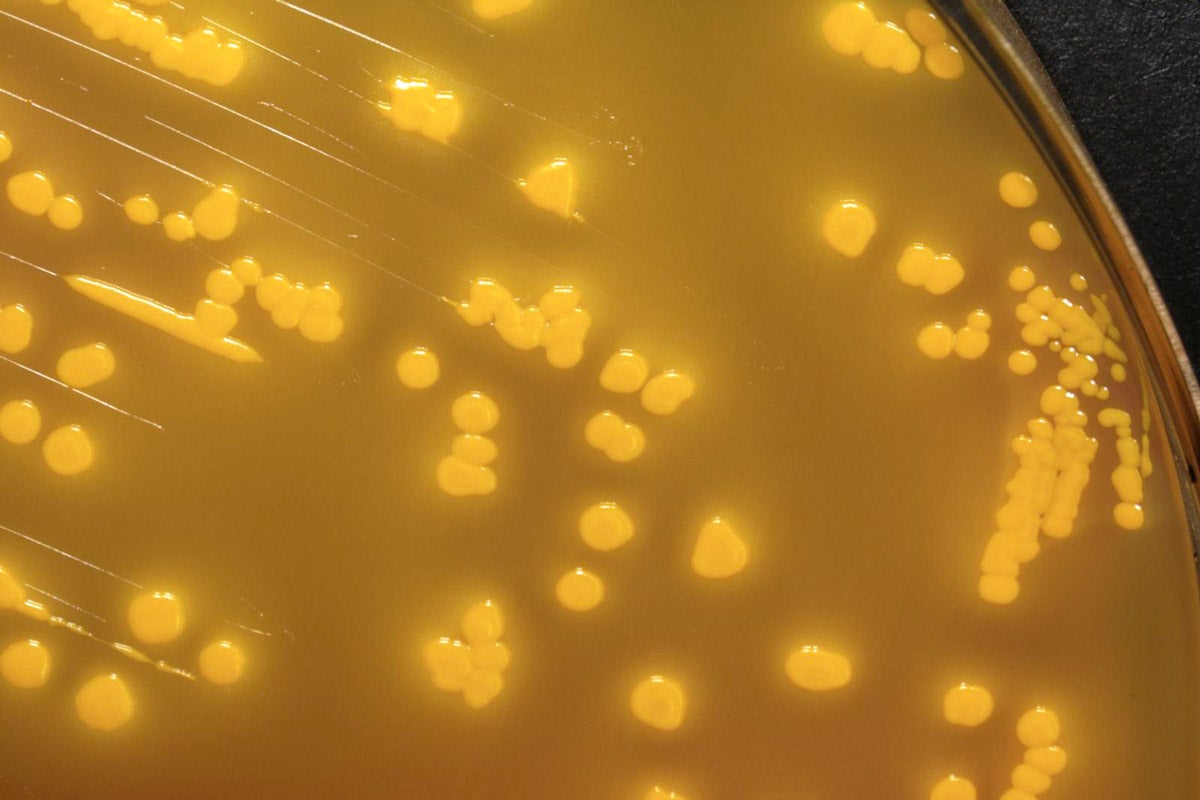

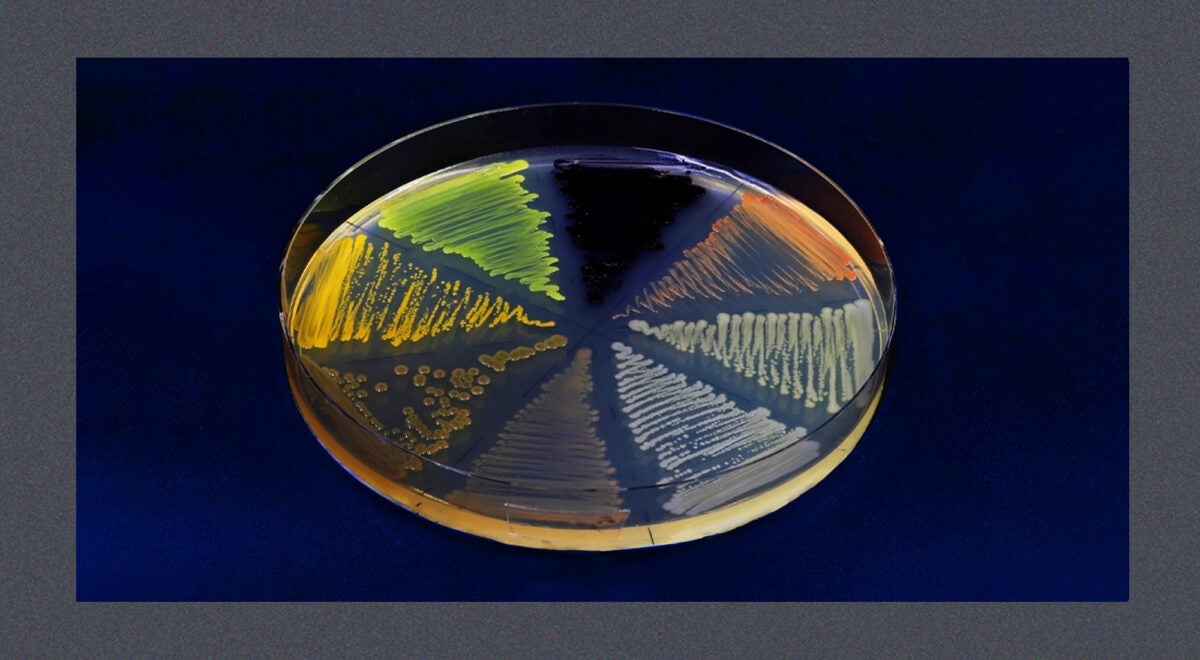

Culture-based tests, the current standard for identifying bacterial pathogens and determining what therapies they are susceptible to, can take three days or more, and they require highly trained technicians (who often leave low-paying public health jobs because of burnout or to pursue more lucrative paths). Such constraints are even worse in low-resource settings.

To diagnose the Ukrainian soldier with six superbugs, the researchers relied on expensive custom medical equipment and sophisticated diagnostic machinery. Those tests happened only after he had passed through two other healthcare facilities, potentially spreading dangerous pathogens at both.

Why do we not have a rapid, low-cost diagnostic tool? It could dramatically improve surveillance efforts in war zones or during other humanitarian crises—earthquakes, floods, and other disasters associated with upticks in infections. Yet we are many years away from seeing such a product come to market.

The same is true on the treatment front. Physicians urgently need new therapies for patients suffering from resistant infections, but it has been approximately 40 years since a new class of antibiotics was discovered and commercialized, and few truly innovative treatments are in the pipeline.

The drought of innovation isn’t because the science is intractable; it’s because antibiotics and bacterial diagnostics aren’t money-makers. Industry and investors avoid this space because of the poor economics, and governments have failed to pursue market reforms that many consider essential to reviving antibiotic R&D.

Policymakers in high-income countries should enact “pull incentives,” policies designed to reward the successful development of new antimicrobials for treating drug-resistant infections. They also need to continue collaborating with industry and civic leaders to ensure access to antibiotics where they are needed most and to enhance vaccination campaigns to prevent some infections from occurring in the first place.

The situation in Ukraine is a stark reminder of the myriad means through which bacterial pathogens can spread. In the early months of the war, health authorities in Germany and the Netherlands reported that their infectious disease surveillance systems detected sharp upticks in multidrug-resistant bacteria. These were attributed to the arrival of medical patients evacuated from Ukrainian hospitals and early waves of refugees. In November, Ukraine’s Ministry of Health told reporters that “the problem with antibiotic resistance has reached a critical level” among the country’s injured soldiers and civilians. A few weeks later, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued an assessment of the Ukrainian superbug situation, noting that “urgent capacity building to prevent, detect, and respond to antimicrobial resistance is needed to save lives within Ukraine and limit international spread.”

Infections have always been a feature of war. An estimated two-thirds of the more than 650,000 soldiers killed during the U.S. Civil War died from an infectious disease. A similar trend held in World War II, until the Allies figured out how to mass produce penicillin just ahead of D-Day through a Manhattan Project-like effort and churned out millions of doses. That bit of wartime innovation saved an estimated 300,000 lives and forever changed the course of modern medicine.

Over the last 30 years, however, new antibiotic-resistant pathogens have emerged all around the world and are now a leading global killer. In 2019, they were associated with nearly 5 million deaths and some estimates project as many as 10 million people will die annually from drug-resistant infections by 2050, more than deaths from cancer.

The convergence of modern warfare and historic levels of antibiotic resistance is a troubling dynamic for which the world is ill-prepared. To be clear, this is not a problem specific to Ukraine. Wherever there is war nowadays, there are superbugs. Scores of U.S. soldiers who were injured in Afghanistan returned home with drug-resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumanii that clinicians in the U.S. struggled to treat. Prolonged conflicts in Syria have been linked to increased cases of drug-resistant infections in neighboring countries and in European hospitals. Most recently, Doctors Without Borders warned that already alarmingly high rates of antibiotic resistance in Gaza are likely to get much worse as the war between Hamas and Israel continues.

Most efforts to fight superbugs in contemporary war zones focus on improving basic infection control and prevention measures like handwashing, as well as emphasizing antibiotic stewardship and appropriate use. There have also been steps taken to bolster surveillance efforts in hopes of identifying antibiotic-resistant pathogens as early as possible. In Ukraine, the World Health Organization’s Country Office recently announced that it was donating surveillance equipment and supplies to at least 10 laboratories in regions near the frontline. These efforts have impact and are commendable, but it is like trying to control a forest fire with a garden hose.

The fog of war obscures so much, but military leaders should be clear-eyed about the direct threat drug-resistant infections pose to their soldiers and the collateral damage they inflict on civilian populations near and far. And governments around the world should be bolstering public health surveillance systems to focus not only on viral pathogens but to also better monitor and track drug-resistant bacterial and fungal pathogens. Because in today’s globalized world, what happens on the battlefield doesn’t always stay on the battlefield.

Source image: TopMicrobialStock / iStock