From the Dean

Message from the Dean: The great force of history

As iconic novelist James Baldwin wrote, “The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do. It could scarcely be otherwise, since it is to history that we owe our frames of reference, our identities, and our aspirations.”

This small shift in language isn’t just semantics. It’s a recognition that we cannot empower individuals to get their shots unless we understand—and address—why they haven’t yet done so. We must do more than deliver data and evidence. We have to do it in a way that meets people where they are—and acknowledges how history and their lived experiences impact their decisions.

We are living in a traumatic time, and the overlapping epidemics of COVID-19, chronic illness, and centuries’ worth of systemic inequity are especially pronounced for communities of color. Another piece in this issue, The Age of Trauma, looks at how such factors can cause what Bizu Gelaye, associate professor of epidemiology, describes as “toxic stress.”

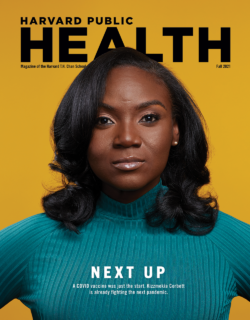

Reading this issue of Harvard Public Health, I was struck by that notion again and again. First, there’s the feature interview with Kizzmekia Corbett, leading coronavirus expert and assistant professor in the Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases. In it, she aptly refers to those who haven’t yet been vaccinated as “vaccine inquisitive” rather than “vaccine hesitant.”

This reality has long been top of mind for Kim Rhoads, MPH ’06, a physician and associate professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California San Francisco, whose story is also featured in this issue. She founded Umoja Health to provide COVID-19 testing and vaccines specifically for Black residents of San Francisco and Oakland, many of whom are justifiably wary of medical institutions.

Her strategy was simple: Show up for people. Listen to them. Prove that there are doctors out there who are looking out for them. This approach, which she refers to as “year-round, nontransactional engagement,” is essential to rebuilding trust with communities that have long faced exploitation and neglect by our health care system.

Building trust also means ensuring that progress in public health benefits everyone. As we’ve seen so vividly this past year, marvels of medical innovation are saving countless lives. But we must ask ourselves: Who will they serve?

It’s the question at the center of Artificial Intelligence’s Promise and Peril, which describes not only the incredible promise of artificial intelligence but also the urgency to remove algorithmic bias toward people of color, whose health histories are all too often excluded from the data.

By any measure, we are living in an extraordinary time for public health, one that each of us will undoubtedly carry with us for years to come. My hope is that this period of history will challenge our existing frames of reference—and deepen our aspirations to create a more just and inclusive world.

Photo: Ben Gebo / Harvard Chan School

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.