Opinion

Public health needs to reform—here’s the way forward

COVID-19 was a referendum on public health. And in its moment in the spotlight, the profession could not deliver. That’s especially true in the U.S., where the virus has killed more than one million people, exceeding the toll in any other country by a wide margin. Structural racism, favoritism for white-collar workers and the well-educated, an underfunded patchwork of local, state, and federal agencies, and deep societal disagreements over collective responsibility and individual liberty all contributed. But the virus also exposed our inability to answer two basic questions: What is public health and who does it?

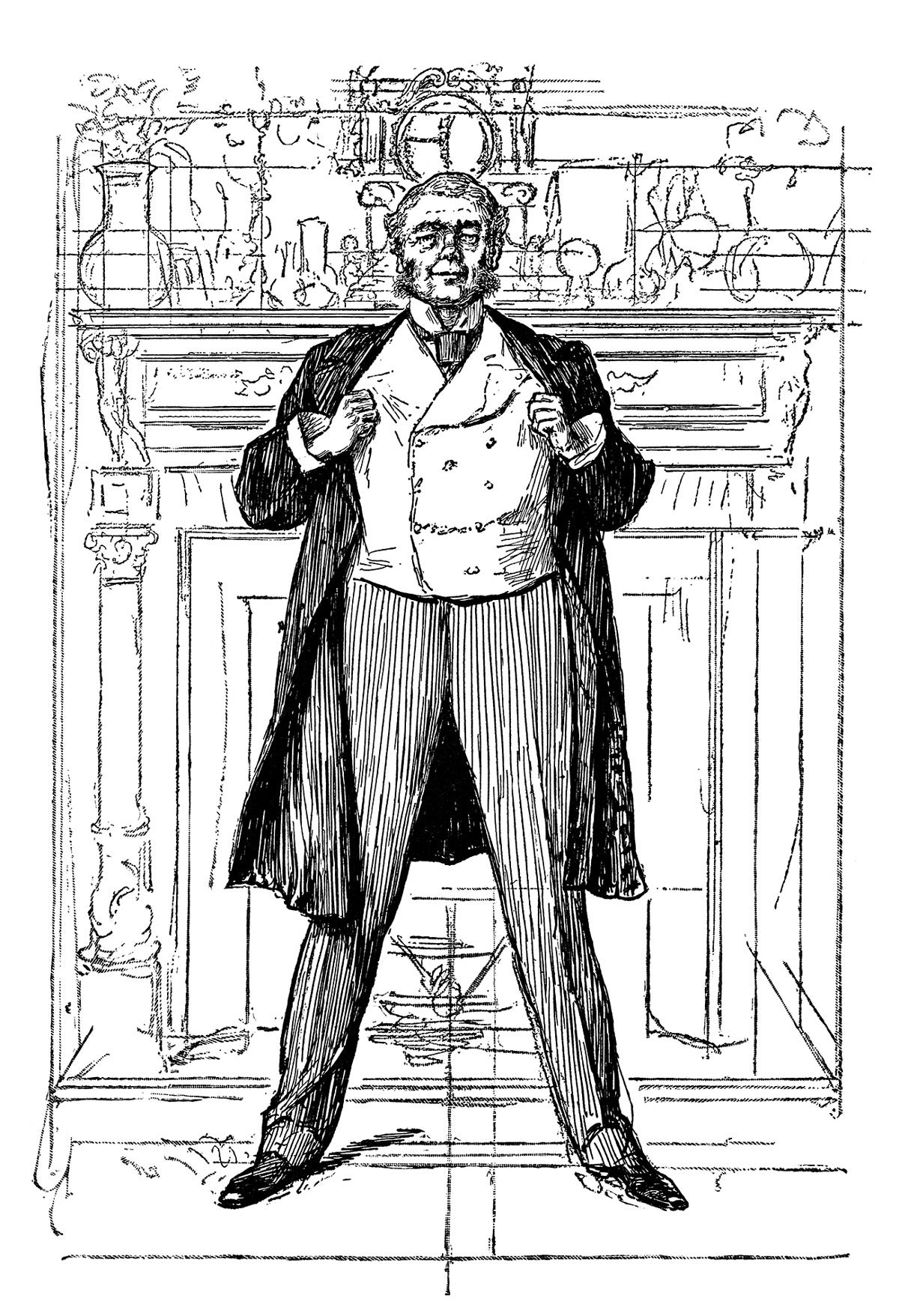

We used to know the answers: Public health protected people from the ravages of industrialization, and anyone who did such work was included. This was in the late 19th century, when creating protection meant developing expertise around a core set of tools—statistics, record-keeping, and epidemiology—then responding to the data with water filtration and sewerage, creating city councils to link engineering works for sanitation with political institutions for urban management. Private water companies were brought under municipal authority to better safeguard citizens, while occupational and housing oversight made cities safer for workers and families. These innovations dovetailed with lively conversations about the organization of society and the need to distribute resources fairly. By the end of the 19th century a new profession emerged, under the name of public health, and often personified as a Sanitarian.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

In this golden age of its influence, public health was led by progressive elites and activists making whole-of-society efforts to advance a fairer, better performing social order. New disciplines such as bacteriology were tapped to control and prevent diseases alongside new technologies to improve water and sewer systems. Statistics were collected and analyzed to identify problems, evaluate interventions, and shape public policy, which led to building and housing codes, workplace safety standards, antitrust laws and other legislation. While solving technical problems and developing regulations was important, public health was fundamentally engaged in achieving broad social objectives.

Public health was at the center of progressive reforms, and its local, state, and federal institutions carried authority. Public health pioneers promoted voter enfranchisement, tax policy, and rights for women and minorities. They launched progressive taxation, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, food and drug purity laws and laboratories, policies for universal education, vaccine programs, and more.

Amidst the sweeping change of the early 20th century were seeds of discord that grew into conflicts, determining which areas developed and which whithered. Despite public health’s unifying name and generically embraced progressive vision, there was no agreement on how it should professionalize or what institutional structures would define it. There was also disagreement between the disciplines and professions on the relationships that tied them to public health, as well as a split over the primacy of environmental versus individual approaches. There was no common authority to resolve these disputes. And while some public health advancements were wildly popular, the public was not universally receptive to progressive fervor. Vaccine mandates were hotly contested, and efforts at gender and racial equality faced resistance as well.

“Public health protected people from the ravages of industrialization, and anyone who did such work was included.”

Bacteriology and epidemiology both had been the province of physicians, which allowed them to draw on established professional networks in the contest for institutional influence, an advantage the other emerging areas did not share. They began organizing schools of public health that excluded sanitary engineering, meaning sewerage, water filtration, and other urban services. Also cast out of the prestigious new academic specialty were public health nursing, community engagement, voter enfranchisement, and other efforts aimed at developing broad influence. Previously prominent, women were largely excluded. The dominance of laboratory sciences was affirmed in 1922 when bacteriologists at Harvard abandoned the Harvard–MIT School for Health Officers in favor of their own Harvard School of Public Health, following the laboratory-focused model of public health established by Johns Hopkins in 1916. This trend toward the life sciences accelerated sharply after World War II, with vast increases in life sciences funding via the National Institutes of Health.

We can see the effects of this split in the U.S.’s response to COVID. Decades of investment in medicine and life sciences yielded quick improvements in clinical management and led to successful therapeutic approaches and effective vaccinations, all in timelines previously unimagined. Epidemiology and quantitative areas revealed almost in real time the pandemic’s spread and its consequences. Within two months of the earliest U.S. cases, public health researchers had documented the disproportionate health and economic impact on Black Americans and other people of color.

However, greater risks and higher mortality for marginalized groups were the direct result of public health abandoning its golden-era fight against social inequalities, a move that also undermined the field’s credibility. The overall low trust in health and medical authorities stemmed from elites’ long-term neglect of societal engagement and a failure to cultivate relationships with ordinary people or even the government bureaucracy of actual public health. Without the other parts of the old public health, life scientists found themselves without the once-strong links with government services and the health system beyond clinical medicine. We had specialists with deep insights into the problem, but no ability to share them with the public, and no coherent bureaucracy to implement them.

In some ways, the road ahead is also the road behind. Where public health once engaged ordinary citizens in debates about societal performance, it must do so again. Where it once championed rights and political inclusion for the marginalized, it must return to communities and regain their trust. Where women and minorities were once essential, they must be re-enfranchised. Where funding for public health research is now largely controlled by the NIH, we need to democratize it. Where disciplines were disdained at top educational institutions, we must re-engage. To our past choices, COVID brought retribution. In response, we must once again embrace as our ultimate objective making public health equal public wealth.

Top image: WhiteMay / i Stock