Feature

Universal health care may drive the vote in Puerto Rico

This story is a copublication with 9 Millones, an independent platform for community-driven journalism in Puerto Rico. You can read their Spanish-language version of this story here.

An alliance between two political parties in Puerto Rico is challenging politics as usual with a progressive touchstone: establishing a single-payer health care system for the archipelago’s 3.2 million residents.

Leading the movement is Juan Dalmau Ramírez, an attorney and former local senator who is making his third run for governor, now as the nominee of the alliance between the Puerto Rico Independence Party (known as PIP) and the Citizen’s Victory Movement. His vision, he told Harvard Public Health, is about “looking to remove private insurers as intermediaries from the health care system in Puerto Rico.” (The candidate is not related to the author of this piece.)

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Dalmau is troubled that even with a health care budget of $6.6 billion—the largest area of spending in Puerto Rico’s budget—people still have difficulty accessing health services. Health systems experts say patients must wait months for critical appointments, providers are often far from where they live, and health insurance doesn’t fully cover their costs.

Nearly 70 percent of Puerto Ricans rely on Medicaid, Medicare, or CHIP for their health coverage, which is managed by the Puerto Rico Health Insurance Administration, part of the islands’ public health department. That public infrastructure contracts all care out to managed care organizations—which have been shown to deny treatments.

Dalmau’s party proposes to combine these federal funds with money from Puerto Rico’s general budget and cut insurers out of the publicly funded system. The proposal would create a National Health Insurance Corporation, organized as a cooperative where the policyholders, beneficiaries, and the government of Puerto Rico would be members and shareholders.

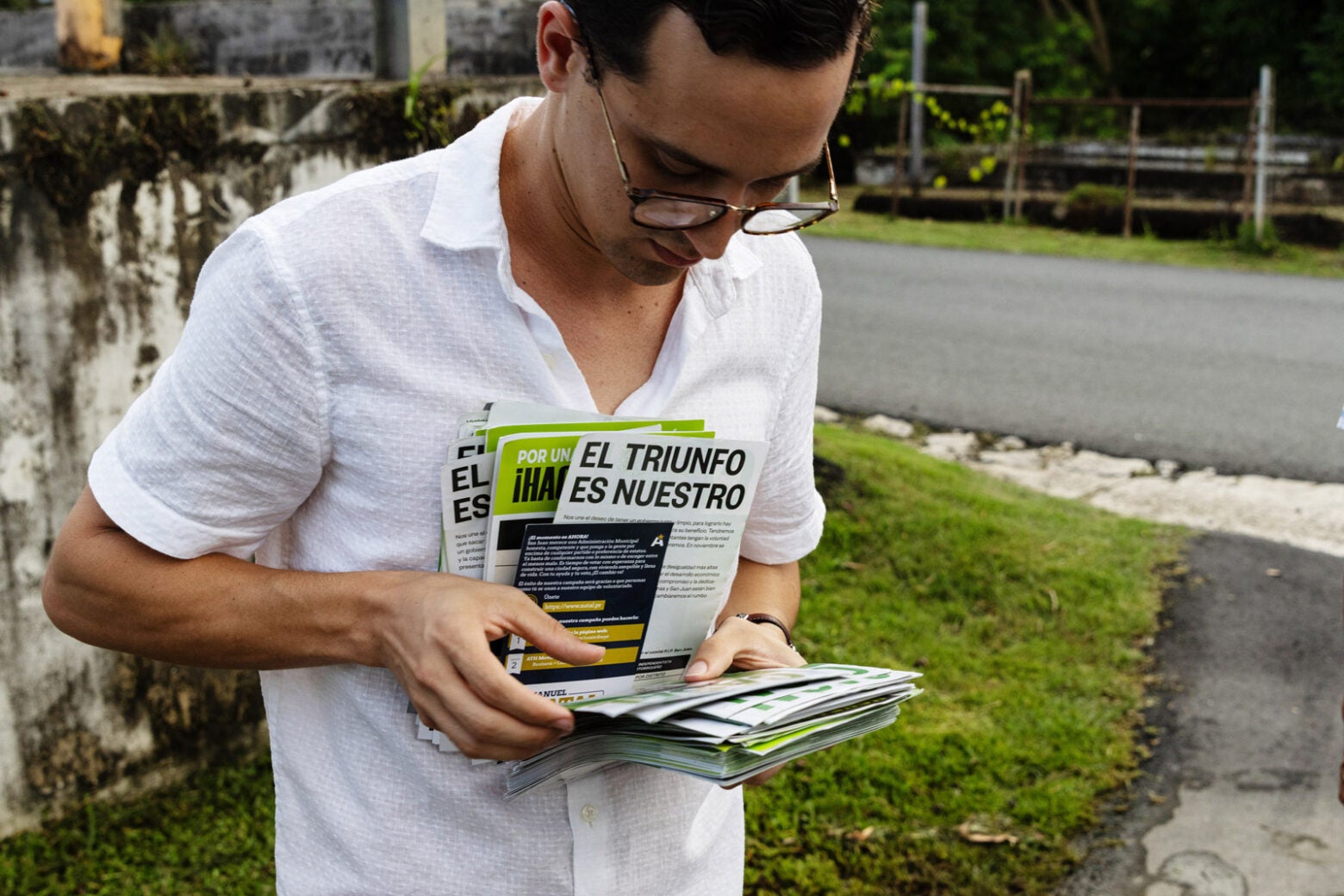

Gabriel Casals Nazario, who is running for Puerto Rico’s House of Representatives, prepares materials for canvassing in Caimito, a neighborhood/district in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Carlos Berrios Polanco

Nazario speaks with a local constituent.

Carlos Berrios Polanco

Dalmau also wants to see greater attention to primary care and more focus on nutrition and physical activity; he hopes a shift toward prevention could help reduce rates of chronic disease in Puerto Rico, where chronic disease rates are among the highest in the U.S., according to the Center for Disease Control’s Behavior Risk Surveillance System.

Alexandra Rivera-González, a professor who studies health systems at the University of California Merced Health Science Research Institute, says single-payer programs have been part of the political conversation in Puerto Rico for years. What makes Dalmau’s proposal different, she says, is its foundation in research and expert consultation. “It’s bringing a holistic perspective to the restructuring of the health care system,” she says.

A major problem any health care initiative must address is attrition. More than 8,000 doctors closed their medical practice in Puerto Rico from 2009 to 2022, according to the Puerto Rico Health Depart. Many of them are leaving Puerto Rico for opportunities in the United Sates that offer better pay, less bureaucracy, or better working conditions.

Heriberto Marín Centeno, an economist and professor at the University of Puerto Rico’s School of Public Health, says considering these points of friction was central for him and other authors of the PIP’s health care proposal. Much of the funds spent in the current system “are being diverted as administrative expenses and as profits for the insurance companies,” he says. “A significant portion of the resources … could be used to treat the health of the population—to pay for the services of our health professionals and our providers,” he says. PIP’s proposal would require that 95 percent of the corporations’ revenue be used to pay for direct medical services. (In 2022, the amount of money spent on direct medical services was under 89%.)

Polls show the alliance has the best chance yet of winning the governor’s race, with Dalmau in the running as the PIP candidate. A poll two weeks ago from El Nuevo Día, Puerto Rico’s largest newspaper, shows him in second place—the first time in history the two main parties aren’t leading in the polls. Universal health care often features in alliance candidates’ stump speeches. Perhaps this is not surprising: One survey by a progressive polling firm found 46 percent of Puerto Ricans named health care as their top concern, and 62 percent support Medicare for All (which is very similar to the alliance’s proposal).

A single-payer health plan may not be as controversial in Puerto Rico as in other parts of the United States. After all, the island actually had a socialized care system up until 1993. As Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration explored universal health care options, Puerto Rico seized the moment to build a public health infrastructure, according to Carlo Bosques Casillas, a medical student who collaborated on the PIP’s health care proposal and who founded Proyecto Arbona, an initiative to teach medical students about the history of health care in Puerto Rico.

Roosevelt developed a close relationship with Luis Muñoz Marín, a Puerto Rican politician who became the island’s first democratically elected governor in 1949 and held the office for the next 16 years. Marín introduced a regionalized universal health care system in 1957, which became known as the “Arbona System” after Guillermo Arbona, the secretary of health who developed it. Modeled on England’s National Health Service, the government owned Puerto Rico’s hospitals and other health care infrastructure.

The Arbona System focused heavily on preventive care to control infectious diseases. Each of the 78 municipalities in Puerto Rico had at least one Center of Diagnosis and Treatment, clinics that were patients’ first point of health systems contact and offered immunizations, medical evaluations, basic treatments, and interventions for minor medical emergencies. There were also 12 regional hospitals. More specialized care was given in medical centers in major cities, in particular Centro Médico, which continues to be Puerto Rico’s largest hospital. These three levels of facilities meant that people always had clinics nearby, and the care was free for all.

The Arbona System started to run into problems in 1965 when the United States passed legislation to offer Medicare and Medicaid, Bosques says. Medicaid capped the funds available to the Arbona System, and it expanded the private health sector. By 1970, there was a marked division between the private and public health system—a change whose effects were felt over the coming years.

By 1979, political leaders had begun to privatize the system. By 1993, the Arbona System was in tatters, and then-governor Pedro Roselló set up the current system, in which government funds pay for private health insurance plans.

Dalmau and his Alliance are proposing a single-payer system rather than the socialized program of the Arbona System. A government insurance plan would cover all Puerto Ricans’ medical costs—much like the “Medicare for All” proposals in the continental United States, and the way the Canada’s system operates—but Puerto Rico would not own the health infrastructure. (Individuals could still purchase private, supplemental coverage.)

A group of canvassers walk in Caimito, the second-largest barrio in San Juan, six weeks before the election.

Carlos Berrios Polanco

If Dalmau is elected, his health plan will still face challenges. His alliance will need a legislative majority—which is a real possibility for the first time—and he will face a big fight from the health insurance industry, which would effectively be shut out of managing government funded health care plans by this proposal. (The Medicaid and Medicare Advantage Products Association, a nonprofit made up of private corporations offering private plans funded by Medicaid and Medicare, declined to comment on the proposal.)

And Dalmau will also need approval from Washington, which may be a tall order because Puerto Rico has no vote in Congress, and Republicans are attacking Vice President Kamala Harris over her past support for Medicare for All. Whether Harris or former President Donald Trump wins in November, the politics around this kind of single-payer proposal could be complicated.

But Dalmau thinks the time has come.

“We cannot continue with a model that failed and is copied from the U.S. system where health care is run for profit,” he said at a forum hosted by the Association of Puerto Rican Hospitals earlier this month. “That is not being anti-American, pro-independence, [or] socialist. … We can’t have insurance companies deciding who lives and who dies in this country.”

Carlos Berrios Polanco supported in the reporting of this story.

Top image: Juan Dalmau announces his candidacy for governor of Puerto Rico at the Independence Party’s convention in San Juan, Puerto Rico in December 2023. (Carlos Berrios Polanco)