News

FDA privately rejected Philips’s claims that recalled CPAP machines were safe

This article was originally published by ProPublica and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

In the winter of 2021, with its stock price plunging, lawsuits mounting and popular breathing machines pulled from the shelves, Philips Respironics made a surprise public announcement.

The company said the sleep apnea devices it had recalled only months earlier had undergone new safety tests and did not appear to pose a health threat to the millions of patients who relied on them to breathe.

It was a remarkable reversal for the global manufacturer, which had drawn headlines after admitting that an industrial foam placed inside the devices could break apart in heat and humidity and send potentially toxic and carcinogenic particles and fumes into the masks worn by users.

The new results, Philips said, found the machines were not expected to “result in long-term health consequences.”

But a series of emails obtained by ProPublica and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette show the Food and Drug Administration quickly rejected those safety claims, telling Philips that the new tests failed to account for the impact on patients who had used the devices for years. The FDA also said it still considered the machines a significant health threat that could inflict severe injury or even death.

“These tests are preliminary,” the agency told Philips. “Definitive conclusions cannot yet be drawn in support of reduction in hazards.”

The FDA did not publicize its assessment, even though patients across the country were at risk and an untold number continued using their recalled machines while they waited on Philips to send replacements.

At the time, the FDA made only one public reference to the dispute—on the fourth page of a 14-page letter to Philips in May 2022. To see it, customers would have had to find it on the agency’s website and then wade through scientific language about “cytotoxicity failure,” “novel continuous sampling” and other complex concepts.

Philips went on to publicize more test results, all playing down the potential health dangers. To this day, the FDA has said little about its ongoing disagreement with the company over whether the machines were safe.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

The emails over the course of 2022 were obtained by ProPublica and the Post-Gazette through a public records lawsuit filed by the news organizations against the FDA. Taken together, the exchanges reveal a startling lack of transparency by both Philips and the government while patients and their doctors struggled to make sense of one of the largest and most tumultuous medical device recalls in years.

“The bottom line is that lives were at risk,” said Dr. Bob Lowe, a former emergency room physician and public health advocate in Oregon who used one of the recalled machines. “People have a right to know and providers have a right, or really an obligation, to be fully informed. As a physician, if I don’t know what the dangers are, then I can’t protect my patients.”

In the emails to Philips, the FDA described a litany of concerns, notably that the company’s analysis did not consider the “real world” use of the devices, which send air directly into the noses, mouths and lungs of patients for hours at a time.

Philips had brought on independent testing labs to assess whether the chemicals and particles released into the masks of patients reached dangerous levels, but the government in its emails said the testing program was “limited in its utility and does not fully assess or account for all risks.”

“FDA has not accepted the data or Philips Respironics’ conclusions,” Denise Hampton, with the FDA’s Office of Health Technology, wrote to the company in one of the emails.

It wasn’t until October 2023—nearly two years after Philips started promoting the favorable test results—that the FDA released a public statement about its concerns, saying that testing and analysis were not “adequate” and that Philips had agreed to conduct additional studies.

Richard Callender, a former mayor in Pennsylvania who used his sleep apnea machine for six months after the recall, said patients should have been given details far earlier.

“We deserve that. If they had concerns they should have at least informed the public,” he said. “Don’t let everybody walk around saying, ‘Hey, I’m OK because [Philips] told me they think it’s all right.’”

The FDA defended its handling of the matter, saying it released the statement in October after completing an analysis of the company’s test results. “Any health determination made by the FDA is science-driven and based on thorough analysis of the information presented to the agency,” it said.

The agency said it “has been clear” about the government’s concerns with the foam in public alerts and other communications and has maintained its position about the potential health risks.

Lowe, however, said the FDA waited far too long to publicly challenge Philips as the company repeatedly told patients that the devices were safe.

“It’s not full disclosure,” he said.

Philips did not respond to specific questions from ProPublica and the Post-Gazette, but it has previously said that the tests found the foam caused no “appreciable harm” to patients and that the company would continue to carry out additional tests.

In its emails to the FDA, Philips said that the favorable findings were based on the “worst-case chemical release” and that testing had found particles from the foam did not exceed safety levels.

While Philips continues to defend the safety of the devices, the company late last month announced it would not sell any new sleep apnea machines and other respiratory devices in the United States under an agreement with the federal government.

Days later, the FDA said it had received 561 reports of deaths associated with the machines since 2021.

From the outset of the recall, there was little debate that Philips had a serious problem: Noise-reducing foam that the company had fitted inside the devices years earlier was crumbling.

Both Philips and the FDA at the time described potential health risks for patients exposed to the material, including respiratory tract illnesses, headaches, nausea, and toxic and carcinogenic effects.

Philips, however, began to walk back its warnings in December 2021, six months after the recall began. And by the following year, the company made multiple announcements about the new test results.

In email exchanges, the FDA challenged the “significant limitations” of the company’s testing program as well as efforts to change an earlier evaluation of the health risks conducted by about a dozen company officials. The 2021 internal assessment was damning, describing the deteriorating foam and dangerous chemicals and declaring the risk to patients who used the machines “unacceptable.”

Months later, Philips turned in a modified evaluation to the FDA, lowering the threat level from “crucial” to “marginal.”

Inside Philips, scientists and others were also alarmed, criticizing the company for minimizing the health risks without carrying out comprehensive testing to determine whether the machines could inflict serious harm, according to interviews and internal communications obtained by ProPublica and the Post-Gazette.

The dispute reached the company’s highest levels. Medical director Hisham Elzayat broke ranks and refused to sign the evaluation that downgraded the risk level, according to court testimony and the internal communications.

“I haven’t seen or heard anything that makes me decide acceptable risk,” he wrote at the time.

In another message, he noted about the evaluation, “There is nothing I can do about it.”

He also wrote, “If only all this effort is steered towards fixing the problem instead of hiding it.”

Elzayat, a cardiothoracic surgeon who still works for Philips and whose differences with the company were described in a federal court hearing in October, declined to comment.

According to the court testimony, after Elzayat refused to endorse the new evaluation, he was removed from the team inside Philips that was handling the crisis and stripped of his access to data about the foam.

Another company supervisor also raised concerns, complaining about the company’s push to change the evaluation, internal communications show.

“They desperately want to make changes,” the supervisor wrote. “I am trying to limit what they are doing.”

ProPublica and the Post-Gazette are withholding the supervisor’s name because of fear of reprisals.

Another official at Philips cited similar concerns, writing about the actions by a company manager to ensure that a testing lab reported favorable results. “You wouldn’t believe the magic he worked to ensure that compound was labeled a non-risk,” the official wrote.

The debate was captured in internal communications, some of which have been turned over to the Department of Justice. The DOJ has been carrying out a criminal investigation, according to sources familiar with the probe and a document reviewed by the news organizations.

Philips, which has said it is cooperating with authorities, declined to answer questions about Elzayat’s role in the controversial evaluation of the foam.

ProPublica and the Post-Gazette have reported that the company held back more than 3,700 complaints about the foam degradation from customers and the government before announcing the recall. The news organizations recently obtained more records from the FDA that identified an additional 1,100 complaints that Philips did not turn over to the government before the recall.

Federal law requires medical device makers to submit reports about malfunctions, patient injuries and deaths to the FDA within 30 days. Philips has said the company reviewed the complaints on a case-by-case basis and gave them to the FDA after the recall out of an “abundance of caution.”

The private debate about whether the machines were safe played out as hundreds of thousands of people were left to decide whether to continue using their recalled devices while waiting for a replacement from Philips. Many reached out to members of Congress, who forwarded a series of complaints to the FDA, records show.

“Having to choose whether to continue using a life-saving device and risk further health complications or to stop using them altogether and risk death is an unthinkable decision to make,” Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick, R-Pa., wrote to the agency in 2022. “It is imperative that patients and healthcare providers have the best guidance.”

The back-and-forth between federal regulators and Philips also unfolded as longtime users of the devices and their relatives stepped forward to report illnesses, including throat, lung, esophageal and nasal cancers. Some described deaths of wives, husbands and other family members.

ProPublica and the Post-Gazette previously identified reports that described nearly 2,000 cases of cancer, 600 liver and kidney illnesses, and 17,000 respiratory ailments.

Medical experts interviewed by ProPublica and the Post-Gazette say that it may take years to determine the health consequences but that early findings are worrisome. The devices tested positive numerous times for genotoxicity, the ability of a chemical to cause cells to mutate, a process that can lead to cancer, company records show.

The biggest challenge, they said, is conducting more comprehensive testing, including an epidemiological analysis that tracks the health of people who used the machines over years.

“You would want more than lab tests to really confirm that these devices are safe,” said Kushal Kadakia, a public health researcher at Harvard Medical School who has written about the recall. “You’d want data from patients over multiple years.”

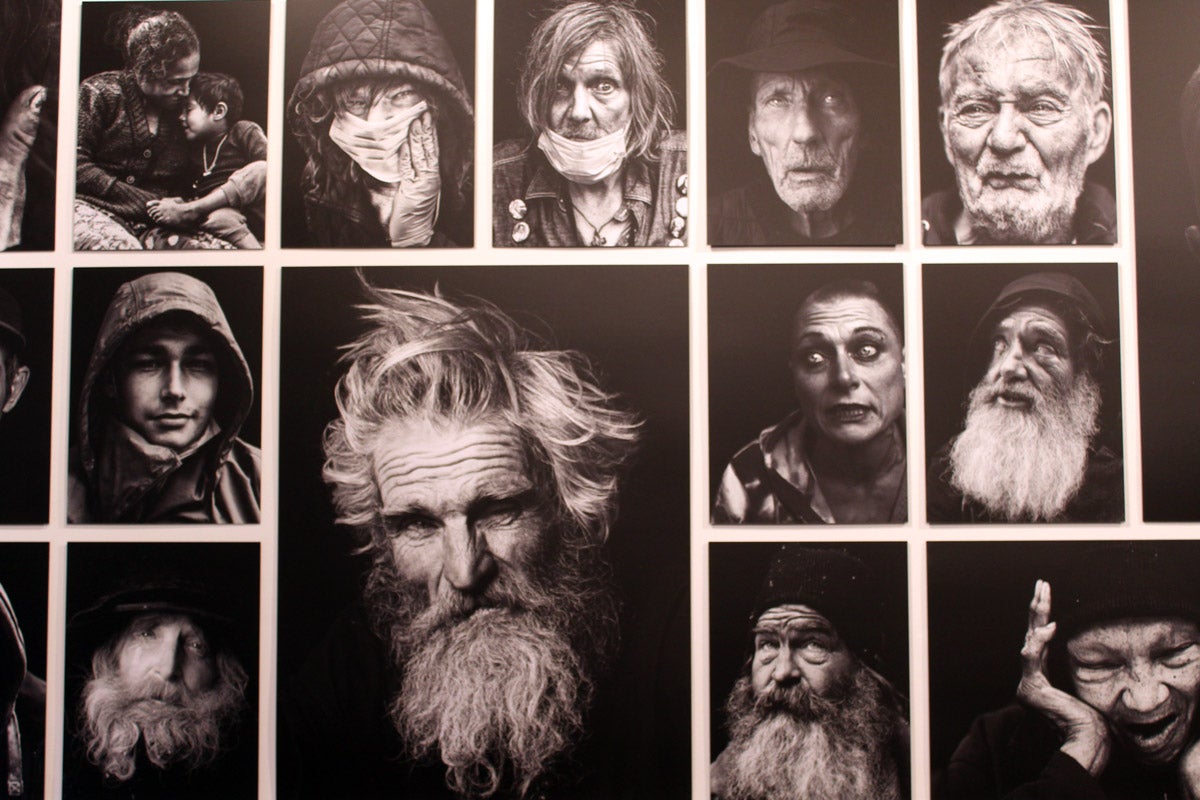

Top image: sokko_natalia / Adobe Stock