Feature

Despite warnings, Texas rushed to remove millions from Medicaid. Eligible residents lost care.

This article was originally published by The Texas Tribune and ProPublica.

For three years during the coronavirus pandemic, the federal government gave Texas and other states billions of dollars in exchange for their promise not to exacerbate the public health crisis by kicking people off Medicaid.

When that agreement ended last year, Texas moved swiftly, kicking off more people faster than any other state.

Officials acknowledged some errors after they stripped Medicaid coverage from more than two million people, most of them children. Some people who believe they were wrongly removed are desperately trying to get back on the state- and federally-funded health care program, adding to a backlog of more than 200,000 applicants. A ProPublica and Texas Tribune review of dozens of public and private records—including memos, emails and legislative hearings—clearly shows that those and other mistakes were preventable and foreshadowed in persistent warnings from the federal government, whistleblowers, and advocates.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Texas’s zealousness in removing people from Medicaid was a choice that contradicted federal guidelines from the start. That decision was devastating in Texas, which already insures a smaller percentage of its population through Medicaid than almost any other state and is one of 10 that never expanded eligibility after the passage of the Affordable Care Act.

“The difference in how Texas approached this compared to a lot of other states is and was very striking. It wanted everybody off, anybody extra off, even though we knew that meant that state systems would buckle under the pressure,” said Erin O’Malley, a senior policy analyst with Every Texan, a left-leaning statewide advocacy group.

Medicaid rolls swelled nationally during the pandemic, with tens of millions of people added to the program and no one removed. In Texas, the number of people receiving Medicaid benefits grew by more than 50 percent, to six million. When the federal government stopped requiring continuous coverage in April 2023, states had to determine who was no longer eligible.

The question wasn’t whether to remove people but instead how to do it in a way that caused the least disruption and ensured those who qualified stayed on.

To that end, the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) advised states to proceed slowly and rely heavily on existing government data to automatically renew eligible residents, steps the agency believed would prevent poor families from wrongly losing coverage. Congress gave states a year for the so-called “Medicaid unwinding.”

But Texas opted for speed, launching reviews of about 4.6 million cases in the first six months. It also decided against the more vigorous use of automatic renewals urged by the federal government, forcing nearly everyone to resubmit documents proving they qualified. Nearly 1.4 million of those who lost coverage were disenrolled for bureaucratic reasons like failing to return a form or completing one incorrectly, not because they weren’t eligible.

The decision to buck federal government guidelines was one of many that led to serious repercussions for Texas residents who rely on the program.

Among them were children forced to forgo or postpone lifesaving operations such as heart surgeries, said Dr. Kimberly Avila Edwards, an Austin pediatrician and Texas representative for the American Academy of Pediatrics. Children with severe diseases such as sickle cell anemia, as well as those with neurodevelopmental delays and autism, also unnecessarily lost critical care.

One of her colleagues treated a boy with a rare heart condition who lost Medicaid coverage in January after his parents failed to sign a form that even his caseworker was not aware the family needed to complete.

The boy’s parents couldn’t afford his $6,000 monthly pulmonary hypertension medication, nor could they pay for an ultrasound that would help determine whether he could survive without the drugs, said Avila Edwards, who declined to identify him because of medical privacy laws.

“If we have children who are less healthy, who are unable to get the preventative care they need for their chronic medical conditions, that fundamentally should raise concern for all of us,” she said.

The boy was eventually reenrolled in Medicaid after Texas pediatricians persuaded the state health agency to restore his coverage, Avila Edwards said. A Texas Health and Human Services Commission spokesperson said the agency would not restore coverage based on pediatricians’ intervention.

Thomas Vasquez, a spokesperson for the HHSC, acknowledged that the agency “learned many lessons” and is working to improve eligibility processes. HHSC representatives defended the rollout, saying that the agency conducted community outreach and hired more than 2,200 employees.

Texas’s approach to the Medicaid unwinding reflected the state’s long-standing conservative ideology regarding the government-subsidized program, said Simon Haeder, an associate professor at Texas A&M University’s School of Public Health.

As attorney general more than a decade ago, Gov. Greg Abbott helped lead a successful lawsuit against the federal government to ensure states didn’t have to cover more residents under Medicaid as part of the Affordable Care Act. Since then, Abbott and state lawmakers have continued to severely limit the program to mostly children, pregnant women, and disabled adults. Poor adults aren’t typically eligible for Medicaid unless they have children. Parents of two kids must earn a combined income of less than $285 monthly to qualify for coverage.

A spokesperson for Abbott declined an interview on his behalf and did not respond to a request for comment on the state’s handling of the unwinding.

Texas’s stance during the unwinding, Haeder said, was, “We don’t do anything illegal, but we want to get our program as fast as we can down to what it was before the pandemic.”

Ignored warnings

It was inevitable that the COVID-19 public health emergency would eventually end, as would the prohibition against pushing people off the rolls. Federal officials worried about the effects of the unwinding on vulnerable Americans almost from the start. In fact, the Biden administration repeatedly extended the emergency declaration, even after the peak of the crisis, to maintain safeguards that included keeping millions of low-income people on Medicaid.

Once the federal protections were lifted in April 2023, as of April 2023, states were free to cull their rolls. In preparation, federal officials advised states not to review more than 11 percent of their caseloads each month, cautioning that moving more quickly could overwhelm their systems and lead to the wrongful removal of eligible people.

But that was guidance, not a requirement, and Texas chose a far more aggressive plan.

In the first month of the unwinding, the state started the review process for about a million cases, or 17 percent of its caseload.

The federal government in May 2023 pressed Texas on why the state was moving so quickly. State officials downplayed the concerns, writing in an email obtained by the news organizations that they were frontloading people who most likely no longer qualified and were reviewing entire households at once.

Within the first four months of the unwinding, the state dropped more than 600,000 people from Medicaid. The vast majority were removed not because the state determined they were no longer eligible but for reasons such as failing to provide the proper documents in time.

That July, U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra called on Texas and other states to increase the number of eligible people they automatically renewed with existing government data. He warned in a letter that his agency would take action against states that were not complying.

In the same week, a group of employees anonymously emailed HHSC Executive Commissioner Cecile Young and media organizations, claiming senior management had alerted them that tens of thousands of people had improperly lost Medicaid due to the agency’s poor handling of the unwinding. Young’s chief of staff responded in an email that she couldn’t address the allegations of unidentified whistleblowers.

Texas alerted the federal government days later that it had erroneously dropped nearly 100,000 people, according to records obtained by the news organizations.

In August 2023, CMS once again implored the state to stop requiring eligible people to resubmit paperwork proving they still qualified. The federal agency said it appeared that many people didn’t know they needed to reenroll, didn’t understand the forms, or faced obstacles in submitting the required information.

Other states that had taken a similar approach, such as Pennsylvania and Maine, made significant changes. Not Texas.

The state agency flagged to CMS last September that more than 30,000 kids lost their coverage, even though most of them should have been moved from Medicaid to the Children’s Health Insurance Program, according to emails the news organizations obtained through the state’s Public Information Act.

State officials later told the news organizations that 95,000 people had been wrongly removed, instead of close to 130,000, as originally reported to CMS. Asked why the figures had decreased, a spokesperson said the agency “provided approximate numbers as we worked to resolve the issue.” Agency representatives said the state quickly reinstated coverage and implemented changes to prevent further improper denials. They did not provide specifics.

Alarmed by the deluge of disenrollments, advocacy groups, health providers, and newspaper editorial boards began calling on the state last summer to pause the unwinding and ensure people were not incorrectly losing coverage. It did not do so.

In October, after Texas had already disenrolled more than 1.2 million people, the state gave about 400,000 people who likely qualified for Medicaid an extra month to submit paperwork, according to an agency spokesperson.

Still, problems persisted.

In December, Becerra appealed directly to Abbott and eight other governors of states with the highest shares of children who had lost coverage. Texas accounted for nearly a quarter of all children in the U.S. who had lost Medicaid or CHIP during the unwinding, Becerra wrote. He again urged the state to employ a series of actions, including automatically renewing eligible people.

Without providing details, Becerra said the federal government would not hesitate to take action against states that did not comply with federal requirements.

“A one-two punch”

Three months later, Micaela Hoops’ children lost the government-subsidized health insurance for which they had qualified their entire lives. After years of not having to renew their Medicaid coverage under the pandemic rules, the 37-year-old North Texas mother said she was confused about when she was required to reapply and missed the deadline to provide proof of the family’s income.

In other states, the kids might have been automatically renewed using other government information, like quarterly payroll data reported by employers to the state or federal tax records. Instead, Hoops had to frantically reapply seven days after the coverage lapsed in March, submitting 24 pay statements for her husband’s weekly wages as a marketing director for a real estate company. This put the family at the back of a monthslong waiting list.

During that time, Hoops, a stay-at-home mom who homeschools the children, had to take her eldest son to the emergency room for a debilitating migraine. The visit came with a $3,000 bill that she and her husband could not pay. A few months later, the 14-year-old broke his nose while playing with his brother on a trampoline. She paid a few hundred dollars out of pocket for the doctor but couldn’t afford the CT scan required to reset his nose.

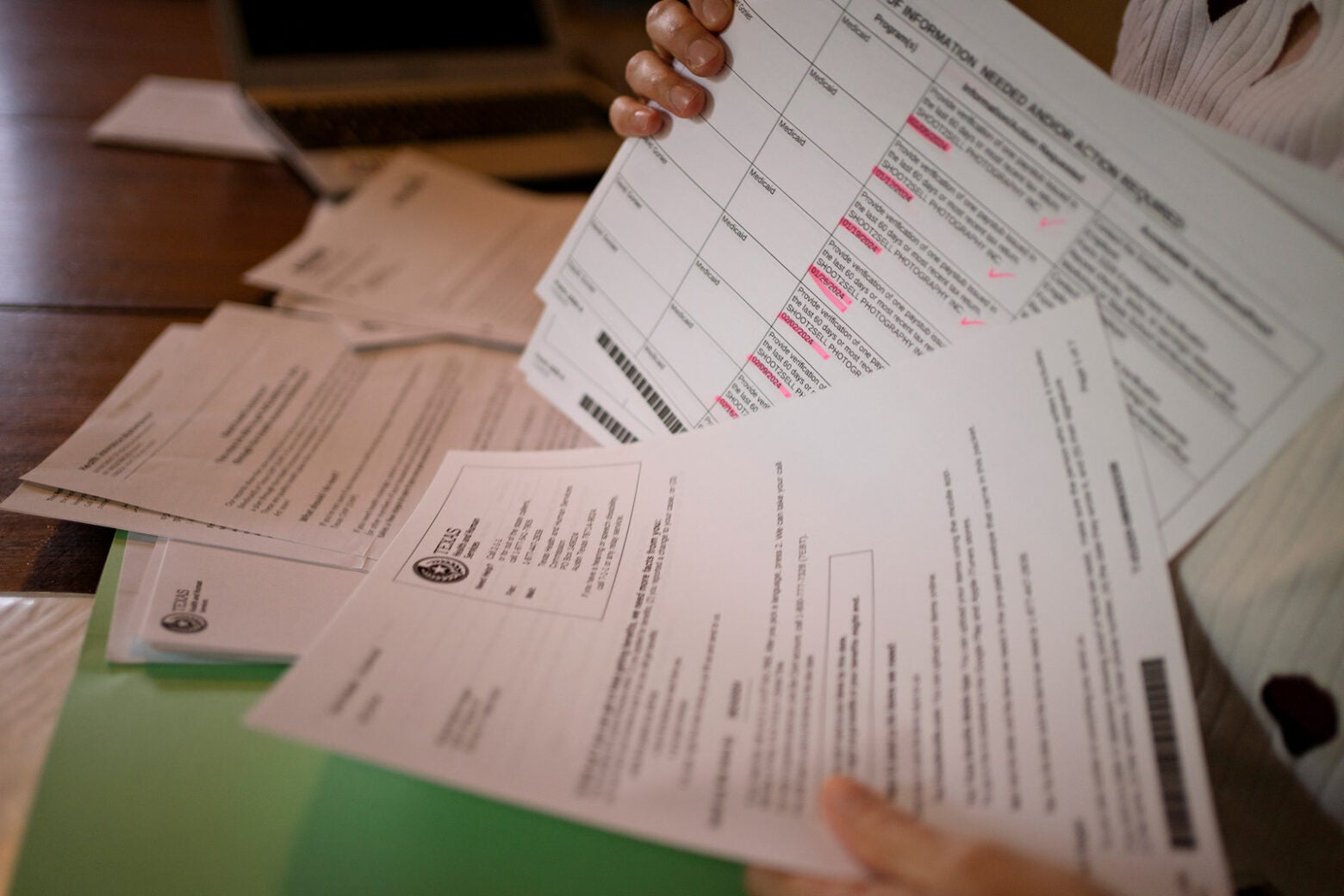

Hoops sifts through paperwork from the Texas Health and Human Services Commission at her home in Sherman.

Danielle Villasana for ProPublica and the Texas Tribune

More than 100 days after Hoops reapplied, the state restored her children’s coverage retroactively. She hopes Medicaid will cover the hospital visit, but her son’s nose remains crooked.

“My children didn’t deserve to go without insurance,” Hoops said. “They’re kids. They have medical emergencies, things happen, and they deserve to be taken care of.”

While Hoops’ children got their Medicaid back, some families that believe they wrongly lost Medicaid are still waiting after being forced to reapply. Texas’s median processing time for Medicaid applications is almost three months, according to a recent agency briefing obtained by the news organizations. This exceeds the federal limit of 45 days for most cases.

The sudden suspension of health insurance for a population the size of New Mexico has had additional ramifications in Texas, including higher treatment costs for hospitals and clinics forced to take on more uninsured patients.

Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston, the largest pediatric hospital in the country, laid off employees this year after significant budget shortfalls. A hospital spokesperson declined to comment, but, in a recent financial filing, the hospital attributed some of the challenges to losing Medicaid patients during the state’s unwinding process.

Across the state, some safety net clinics reported a 30 percent decrease in Medicaid revenue due to the unwinding, said Jana Eubank, who heads the Texas Association of Community Health Centers. She said the extra costs added to challenges for the already financially strapped facilities.

“Some centers are having to lay off staff. Some centers are furloughing staff,” Eubank said. “I’ve got a couple of CEOs that aren’t taking a salary right now. I’ve had centers that are unfortunately having to cut back certain services or extended hours, like behavioral health services, dental services, just because they can’t afford to continue to offer that care.”

Separately, some families that were pushed off Medicaid are also waiting more than a month for food assistance because Texas uses the same eligibility system to process applications for both.

San Antonio Food Bank CEO Eric Cooper said the nonprofit was crushed by demand this summer when families faced sudden medical bills, kids were out of school and the state had a backlog of more than 277,000 food stamp applications. The situation worsened when Texas declined to participate in a federal nutrition program, turning down an estimated $450 million that could have helped feed nearly 3.8 million poor children during the summer. HHSC officials said they could not get the program running in time.

“It’s felt like a one-two punch, the double whammy,” Cooper said.

“We haven’t really felt any relief since the Medicaid unwinding and the official end of the public health emergency,” he added. “It’s still an emergency. It’s still a crisis.”

Federal investigation

In May, after Texas’s unwinding ended, the federal government launched an investigation into long waits faced by people who had applied for Medicaid coverage. Addressing these persistent delays was especially important because they affected eligible people who lost coverage in the past year, Sarah deLone, director of CMS’s Children and Adults Health Programs Group, wrote in a letter to the state.

Former federal officials and health policy experts called the probe a significant step by the agency, which typically works with states behind the scenes.

But CMS has few options to hold Texas accountable if it finds wrongdoing, said Joan Alker, executive director of the Center for Children and Families at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. The Biden administration’s major enforcement tool is yanking federal funding, but that could cause low-income people to lose health insurance and invite a lawsuit from Texas, Alker said. And the investigation likely won’t go anywhere if Donald Trump wins in November, she said, since the former president previously encouraged states to restrict Medicaid access and promised to undo the Affordable Care Act entirely.

CMS spokesperson Stephanie Rossy declined to comment directly on its investigation or on Texas’s handling of the unwinding. But in a statement she wrote that “states’ choices have real consequences for eligible people’s ability to stay covered.”

Texas officials also declined to discuss the probe, but in a letter to the federal agency two weeks after the May investigation announcement, the state’s Medicaid director, Emily Zalkovsky, acknowledged that Texas experienced “severe operational and systems challenges” during the unwinding.

Although the federal probe was welcomed by advocacy groups, as well as some health care providers and Texas families, it’s unlikely to immediately help eligible people who lost Medicaid during the unwinding and are waiting to get back on.

While Hoops’ children have regained coverage, she believes that what her family endured reflects state leaders’ attitudes toward low-income people.

“Maybe they didn’t realize they were making cruel decisions,” she said. Still, she feels like the state’s mentality is basically, “Well, you just shouldn’t be dependent on us.”

Top image: Micaela Hoops with her children at their home in Sherman, Texas.

Update: This story was updated to include comment from the Texas Health and Human Services Commission about the case of a boy with a rare heart condition who lost Medicaid coverage.

Disclosure: Every Texan, Texas A&M University, and Texas Association of Community Health Centers have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations, and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.