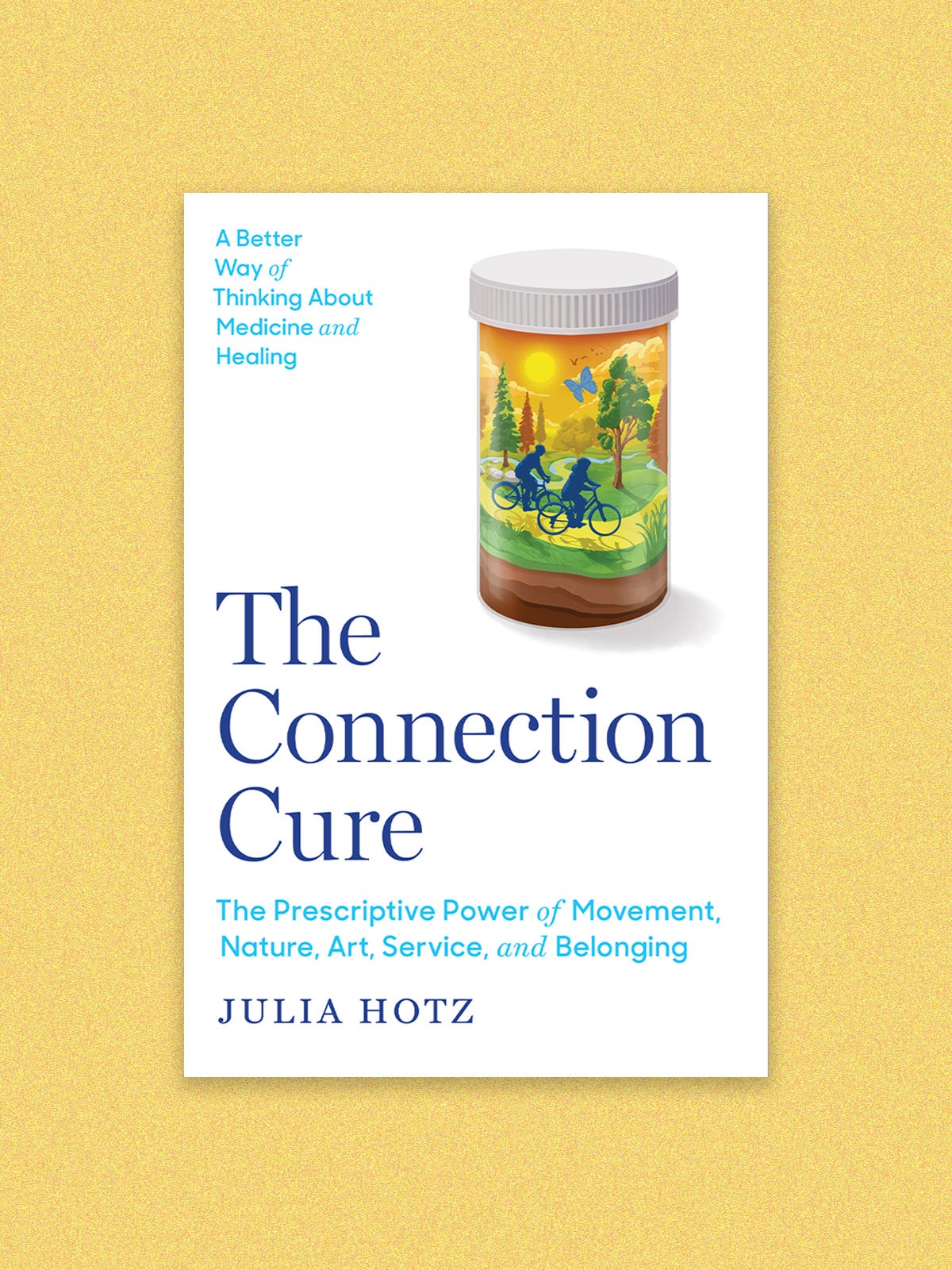

Book

Is social prescribing just what the doctor ordered?

There’s something both revolutionary and glaringly obvious about the “medicine” that journalist Julia Hotz describes in The Connection Cure: The Prescriptive Power of Movement, Nature, Art, Service, and Belonging. In England, doctors send a woman with depression to Chill Therapy, a group that takes swimmers out to sea in bracingly cold water. In Denmark, a man suffering from panic attacks joins Kulturvitaminer, or “culture vitamins,” a ten-week program of visits, sing-alongs, and read-alouds. In Australia, a Vietnamese immigrant with a traumatic childhood is sent to MakeShift, an eight-week art course for unemployed people.

These aren’t just suggestions. They’re actual prescriptions from health care providers, part of a growing international movement known as “social prescribing.”

Social prescribing, Hotz explains, isn’t a replacement for traditional medicine, nor is it the stuff of bogus TikTok cures or the vast consumer “wellness” industry. It’s a practice undertaken by health care providers, based on the idea that conditions such as depression, anxiety, and chronic pain are exacerbated by isolation and loneliness—and that engagement with the world, through exercise, art, and even volunteer service, can be part of a cure.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Social prescribing is now a worldwide phenomenon, with umbrella organizations and an international conference. It’s interwoven, in various forms, into health care systems in Portugal, Singapore, the Netherlands, Canada, and Australia. But it’s hard, Hotz acknowledges, to imagine it broadly adopted in the United States—a nation with a quick-fix culture, a vast pharmaceutical marketing machine, and a health care provider shortage that makes it difficult for clinicians to even uncover the problems that lend themselves to social-prescribing solutions. To work at scale, Hotz argues, social prescribing requires buy-in from the medical system.

She traces the practice’s origins to a priest in 1980s London, who converted a church to a “healthy living centre” with yoga classes, volunteer projects, and a community garden. Eventually, Britain’s National Health Service embraced the program and funded “link workers”—nonmedical staff tasked with connecting patients to services and activities.

From there, the concept spread internationally, often through community-based entrepreneurial interventions—and health systems that invested in care teams to facilitate the connections. Hotz travels around the world to see some thriving social prescribing programs in action, visiting patients in singing groups, nature immersion programs, and aging centers, such as a Norwegian farm called “Impulssenter,” where seniors with dementia find meaning in simple tasks such as packaging eggs.

The problems and solutions Hotz uncovers are compelling, though she sometimes conflates the socioeconomic conditions that lead to bad health with the general malaise of living in a fragmented society. (In a few poignant passages, she describes patients who showed up in a clinic for some mild condition, week after week, and eventually confessed that they just wanted human company.) But while social prescribing advocates are gathering data on outcomes, Hotz concedes that it can be difficult to measure the programs’ effects. As one health worker in Singapore tells her, “It felt a bit awkward to ask patients, ‘Do you feel loved?’”

That might be part of the reason that social prescribing has been slow to spread to the United States, despite our soaring health care costs, aging population, and loneliness epidemic. Hotz cites some scattered successes—“a coalition of thirty therapists in Utah, an addiction nonprofit in Arkansas, and a loneliness relief program for aging adults in New York”—and acknowledges broader structural obstacles in its way, although she doesn’t investigate them fully. American health care is ruled by diagnostic codes and specialist associations. Funding can be a zero-sum game. It would take a concerted policy drive to make social prescribing a commonplace part of the system.

Ultimately, though, Hotz doesn’t aim her argument at providers, insurers, or government officials. She’s writing, instead, for consumers, which could be why she ultimately falls prey to the same quick-fix marketing that she criticizes for most of the book.

Hotz is on the young end of millennial—she’s 30 as she writes her book, and living in Brooklyn—and the book concludes with a cri de coeur for a generation known for screen addiction and high anxiety. In a brief third section, Hotz recounts her own woes: a breakup, work-stress migraines, fear of change. Then she prescribes herself some outdoor activities and group togetherness: a bird-watching class, an early-morning group run up Eighth Avenue in Manhattan, a mindful visit to an art museum.

She also speaks to Cormac Russell, a noted critic of social prescribing, who insists that we shouldn’t need doctors to live in a healthy society. By relying on the medical system, Russell tells her, “we perpetuate the patronizing power imbalance in which the patient is the passive beneficiary, waiting for the benevolent expert doctor to fix them.” By the end of the book, Hotz seems to agree with him, reducing the many programs she visited around the world to “doctor-ordered forced friendships” and suggesting that what we really need is a collective attitude adjustment, so that we stop to smell the roses and appreciate the small things and make every moment count, et cetera, et cetera.

But there is something meaningful about a doctor’s orders: the authority, the documentation, the integration, the follow-through—especially for someone who might not have the resources or wherewithal to simply live life well. Hotz pronounces herself cured, and good for her. But she’s let an entire system off the hook.

Book cover: Simon & Schuster

Republish this article

<p>A new book questions whether we need our physicians to force us to engage with the world.</p>

<p>Written by Joanna Weiss</p>

<p>This <a rel="canonical" href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/mental-health/social-prescribing-book-offers-mixed-perspective-on-a-phenomenon/">article</a> originally appeared in<a href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/">Harvard Public Health magazine</a>. Subscribe to their <a href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/subscribe/">newsletter</a>.</p>

<p class="has-drop-cap">There’s something both revolutionary and glaringly obvious about the “medicine” that journalist Julia Hotz describes in <em>The Connection Cure: The Prescriptive Power of Movement, Nature, Art, Service, and Belonging</em>. In England, doctors send a woman with depression to Chill Therapy, a group that takes swimmers out to sea in bracingly cold water. In Denmark, a man suffering from panic attacks joins Kulturvitaminer, or “culture vitamins,” a ten-week program of visits, sing-alongs, and read-alouds. In Australia, a Vietnamese immigrant with a traumatic childhood is sent to MakeShift, an eight-week art course for unemployed people.</p>

<p>These aren’t just suggestions. They’re actual prescriptions from health care providers, part of a growing international movement known as <a href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/mental-health/uk-experiments-with-social-prescribing-as-mental-health-crisis-grows/" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">“social prescribing.”</a></p>

<p>Social prescribing, Hotz explains, isn’t a replacement for traditional medicine, nor is it the stuff of bogus TikTok cures or the vast consumer “wellness” industry. It’s a practice undertaken by health care providers, based on the idea that conditions such as depression, anxiety, and chronic pain are exacerbated by isolation and loneliness—and that engagement with the world, through exercise, art, and even volunteer service, can be part of a cure. </p>

<p>Social prescribing is now a worldwide phenomenon, with <a href="https://socialprescribingacademy.org.uk/" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">umbrella organizations</a> and an international <a href="https://www.socialprescribingnetwork.com/conference" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">conference</a>. It’s interwoven, in various forms, into health care systems in Portugal, Singapore, the Netherlands, Canada, and Australia. But it’s hard, Hotz acknowledges, to imagine it broadly adopted in the United States—a nation with a quick-fix culture, a vast pharmaceutical marketing machine, and a health care provider shortage that makes it difficult for clinicians to even uncover the problems that lend themselves to social-prescribing solutions. To work at scale, Hotz argues, social prescribing requires buy-in from the medical system. </p>

<p>She traces the practice’s origins to a priest in 1980s London, who converted a church to a “healthy living centre” with yoga classes, volunteer projects, and a community garden. Eventually, Britain’s National Health Service embraced the program and funded “link workers”—nonmedical staff tasked with connecting patients to services and activities. </p>

<p>From there, the concept spread internationally, often through community-based entrepreneurial interventions—and health systems that invested in care teams to facilitate the connections. Hotz travels around the world to see some thriving social prescribing programs in action, visiting patients in singing groups, nature immersion programs, and aging centers, such as a Norwegian farm called “Impulssenter,” where seniors with dementia find meaning in simple tasks such as packaging eggs.</p>

<p>The problems and solutions Hotz uncovers are compelling, though she sometimes conflates the socioeconomic conditions that lead to bad health with the general malaise of living in a fragmented society. (In a few poignant passages, she describes patients who showed up in a clinic for some mild condition, week after week, and eventually confessed that they just wanted human company.) But while social prescribing advocates are gathering data on outcomes, Hotz concedes that it can be difficult to measure the programs’ effects. As one health worker in Singapore tells her, “It felt a bit awkward to ask patients, ‘Do you feel loved?’” </p>

<p>That might be part of the reason that social prescribing has been slow to spread to the United States, despite our soaring health care costs, aging population, and loneliness epidemic. Hotz cites some scattered successes—“a coalition of thirty therapists in Utah, an addiction nonprofit in Arkansas, and a loneliness relief program for aging adults in New York”—and acknowledges broader structural obstacles in its way, although she doesn’t investigate them fully. American health care is ruled by diagnostic codes and specialist associations. Funding can be a zero-sum game. It would take a concerted policy drive to make social prescribing a commonplace part of the system. </p>

<p>Ultimately, though, Hotz doesn’t aim her argument at providers, insurers, or government officials. She’s writing, instead, for consumers, which could be why she ultimately falls prey to the same quick-fix marketing that she criticizes for most of the book.</p>

<p>Hotz is on the young end of millennial—she’s 30 as she writes her book, and living in Brooklyn—and the book concludes with a cri de coeur for a generation known for screen addiction and high anxiety. In a brief third section, Hotz recounts her own woes: a breakup, work-stress migraines, fear of change. Then she prescribes herself some outdoor activities and group togetherness: a bird-watching class, an early-morning group run up Eighth Avenue in Manhattan, a mindful visit to an art museum. </p>

<p>She also speaks to Cormac Russell, a noted critic of social prescribing, who insists that we shouldn’t need doctors to live in a healthy society. By relying on the medical system, Russell tells her, “we perpetuate the patronizing power imbalance in which the patient is the passive beneficiary, waiting for the benevolent expert doctor to fix them.” By the end of the book, Hotz seems to agree with him, reducing the many programs she visited around the world to “doctor-ordered forced friendships” and suggesting that what we really need is a collective attitude adjustment, so that we stop to smell the roses and appreciate the small things and make every moment count, et cetera, et cetera.</p>

<p class=" t-has-endmark t-has-endmark">But there <em>is </em>something meaningful about a doctor’s orders: the authority, the documentation, the integration, the follow-through—especially for someone who might not have the resources or wherewithal to simply live life well. Hotz pronounces herself cured, and good for her. But she’s let an entire system off the hook. </p>

<script async src="https://www.googletagmanager.com/gtag/js?id=G-S1L5BS4DJN"></script>

<script>

window.dataLayer = window.dataLayer || [];

if (typeof gtag !== "function") {function gtag(){dataLayer.push(arguments);}}

gtag('js', new Date());

gtag('config', 'G-S1L5BS4DJN');

</script>

Republishing guidelines

We’re happy to know you’re interested in republishing one of our stories. Please follow the guidelines below, adapted from other sites, primarily ProPublica’s Steal Our Stories guidelines (we didn’t steal all of its republishing guidelines, but we stole a lot of them). We also borrowed from Undark and KFF Health News.

Timeframe: Most stories and opinion pieces on our site can be republished within 90 days of posting. An article is available for republishing if our “Republish” button appears next to the story. We follow the Creative Commons noncommercial no-derivatives license.

When republishing a Harvard Public Health story, please follow these rules and use the required acknowledgments:

- Do not edit our stories, except to reflect changes in time (for instance, “last week” may replace “yesterday”), make style updates (we use serial commas; you may choose not to), and location (we spell out state names; you may choose not to).

- Include the author’s byline.

- Include text at the top of the story that says, “This article was originally published by Harvard Public Health. You must link the words “Harvard Public Health” to the story’s original/canonical URL.

- You must preserve the links in our stories, including our newsletter sign-up language and link.

- You must use our analytics tag: a single pixel and a snippet of HTML code that allows us to monitor our story’s traffic on your site. If you utilize our “Republish” link, the code will be automatically appended at the end of the article. It occupies minimal space and will be enclosed within a standard <script> tag.

- You must set the canonical link to the original Harvard Public Health URL or otherwise ensure that canonical tags are properly implemented to indicate that HPH is the original source of the content. For more information about canonical metadata, click here.

Packaging: Feel free to use our headline and deck or to craft your own headlines, subheads, and other material.

Art: You may republish editorial cartoons and photographs on stories with the “Republish” button. For illustrations or articles without the “Republish” button, please reach out to republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.

Exceptions: Stories that do not include a Republish button are either exclusive to us or governed by another collaborative agreement. Please reach out directly to the author, photographer, illustrator, or other named contributor for permission to reprint work that does not include our Republish button. Please do the same for stories published more than 90 days previously. If you have any questions, contact us at republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.

Translations: If you would like to translate our story into another language, please contact us first at republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.

Ads: It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads, but not ads specifically sold against our stories. You can’t state or imply that donations to your organization support Harvard Public Health.

Responsibilities and restrictions: You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third-party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. Harvard Public Health recognizes that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties aggregate or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

You may not republish our material wholesale or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You may not use our work to populate a website designed to improve rankings on search engines or solely to gain revenue from network-based advertisements.

Any website on which our stories appear must include a prominent and effective way to contact the editorial team at the publication.

Social media: If your publication shares republished stories on social media, we welcome a tag. We are @PublicHealthMag on X, Threads, and Instagram, and Harvard Public Health magazine on Facebook and LinkedIn.

Questions: If you have other questions, email us at republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.