From the editor

Senator Chris Murphy on loneliness and social media regulation

Sen. Chris Murphy sees loneliness as one of the few things in U.S. politics that crosses party lines. The Democrat from Connecticut says the issue matters to him for a number of reasons, not least because he is the father of a teen and a tween. He believes the federal government can take meaningful action to counter loneliness and reknit the social fabric. In a recent appearance at the Studio at Harvard Chan, he said that loneliness is a way to discuss social determinants of health without using that clunky phrase, which he called “a perfect way to end a conversation with regular people.” Murphy spoke with Harvard Public Health Editor-in-Chief Michael Fitzgerald.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

HPH: You’ve acknowledged there’s skepticism about what government can do to improve social connection. In the U.K., the National Health Service allows clinicians and social workers to prescribe social activities. Could this be something that you could see Medicare or Medicaid looking to fund?

Murphy: We have an uphill climb to convince conservatives to broaden the aperture of what can be reimbursed. But it’s a conversation we should have. There’s going to be a natural skepticism from conservatives to spend government money on club memberships or pickleball. And I understand that, but that skepticism only comes from us being so overly restrictive in the way that we have defined reimbursement strategy thus far. And I think conservatives just need to admit that it is not “conservative” to spend billions of dollars on reimbursements that aren’t working. By spending money on helping people build social connection, you might end up spending less money overall.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

HPH: You visited North Carolina, where they are using Medicaid dollars to pay for things like repairing kitchen sinks and plumbing and food-as-medicine programs. At what point do you start calling for broader policy implementation?

Murphy: So I don’t have a deep policy expertise on this stuff. I’m not familiar with what North Carolina is doing. All I know is that the Surgeon General’s report makes it 100 percent clear there’s a direct connection between social connection, loneliness, and how healthy a person is. So why wouldn’t you decide to spend some portion of health care dollars on building social connection if it saves you $100,000 expenditure on an early-onset dementia case?

HPH: You’ve discussed the decline of spirituality, and of religious connection in particular. There is not actually that much research around the impact of spirituality on health, though there are some significant research efforts out there, including a big one at the Chan School. It’s weird to ask this in a nation that had a founding principle of separation of church and state, but is one role for government in fighting loneliness to fund more research around spirituality and connectedness?

Murphy: I am open to it. I don’t think there’s any way to separate the crisis of meaning and identity that exists in this country from the rapid decline in church membership. Common sense tells you that that has to have an immense impact. I’d be interested in seeing what surveys and data can get you here. We need to talk about this more in the public sector. We need to be perhaps more intentional in trying to support church life and support religious institutions.

HPH: You told Vanity Fair that government decisions have helped cause our loneliness epidemic. What has government done, and how can the epidemic trends be reversed?

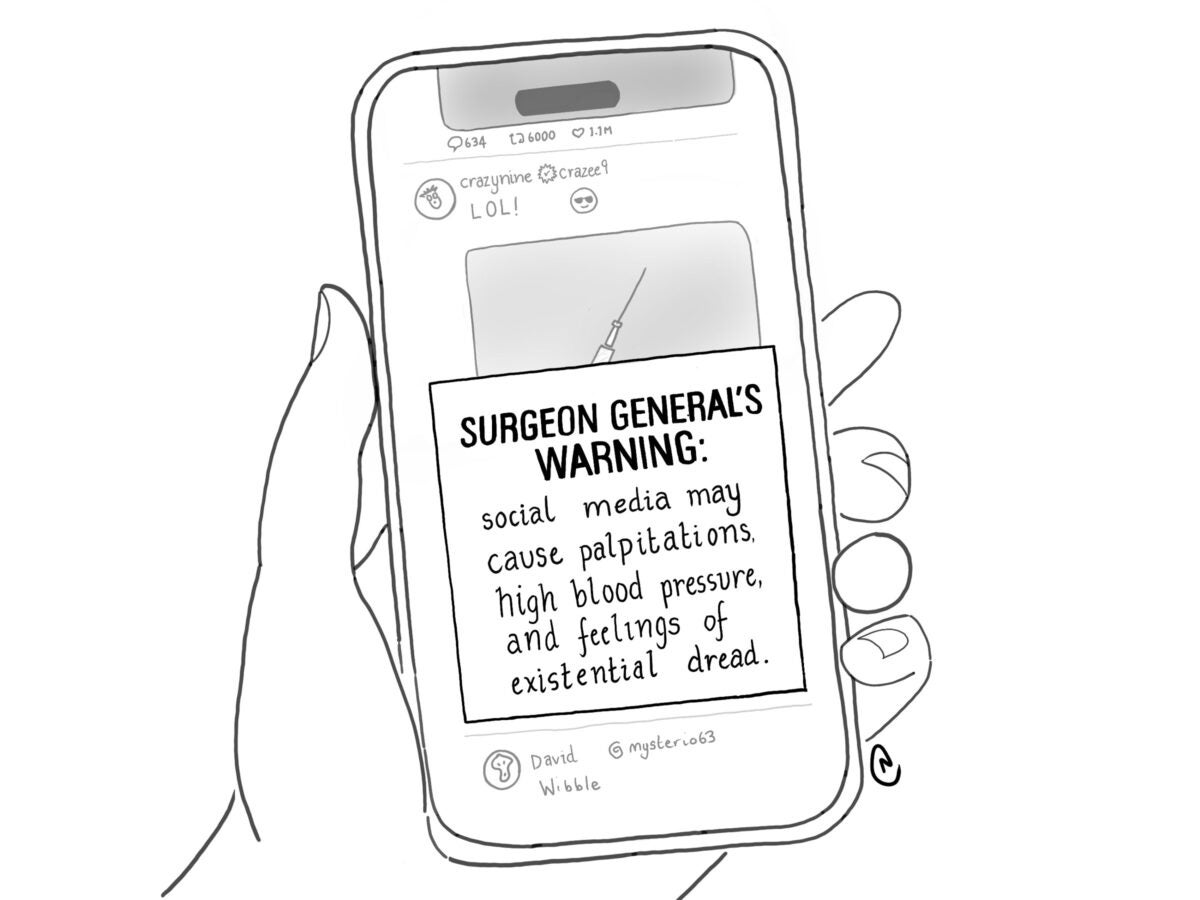

Murphy: Our unbridled enthusiasm for outsourcing and [for] consolidated economic power has left people feeling very alone. The erosion of downtowns and of local communities was a public policy decision, and that has made people feel much more lonely. [With] social media, the choice was not something government did; it was something government didn’t do. When prescription drugs were invented, we very quickly regulated them because we saw that unregulated medicine was going to be damaging. We should have done the same thing with social media as soon as it started to become so pervasive. And our choice not to regulate it had consequences for the country’s emotional health.

HPH: Could self-regulation work, or do we really need government to step in and say, “Here’s how this is going to happen?”

Murphy: Self-regulation of social media will not work. The companies have made it perfectly clear they are interested in only profit and addicting our kids and do not give a shit about the well-being of our families. It is time for government to step in, and I would argue with a pretty heavy hand. That’s why I’ve introduced this [social media] legislation that is fairly tough in terms of requiring parental consent and age verification and a ban on [certain] algorithms. It’s time for government to just decide what’s good for our kids, in consultation with parents.

HPH: You’ve introduced multiple kinds of legislation around social media. Sen. Tina Smith has also done this. How do you see this moving forward in the Congress we have now?

Murphy: The tech industry has a lot of friends in Congress. They spend a lot of money to try to stop regulatory legislation from coming to the floor of the Senate. But I think that there is an unstoppable momentum when it comes to protecting kids online. I think in the next 12 months we will vote on legislation to protect kids online. It’s a pretty nonpartisan issue right now. The two main bills are the one that I have with Tom Cotton [Republican senator from Arkansas], Katie Britt [Republican senator from Alabama], and Brian Schatz [Democratic senator from Hawaii]—the four of us couldn’t find agreement on anything other than protecting kids online—and the other one is Dick Blumenthal, my [Democratic] colleague from Connecticut, and Martha Blackburn [Republican senator from Tennessee]. Again, I’m not sure that Blackburn and Blumenthal work together on anything other than that issue.

Photo: Kent Dayton / Harvard Chan School