People

Is bereavement a public health crisis in the U.S.? This advocate thinks so.

Joyal Mulheron is on a mission to get federal action on bereavement in response to what she calls “an invisible public health crisis.” Her ten-year-old nonprofit, Evermore, advocates for gathering data related to bereavement and establishing a national center for its study. Its website is a repository for information about how to discuss the death of loved ones in different contexts, facts and figures about how such losses affect mortality and health, and scores of conversations with people who’ve lost loved ones. She’s been featured on PBS Newshour and submitted testimony to Congress.

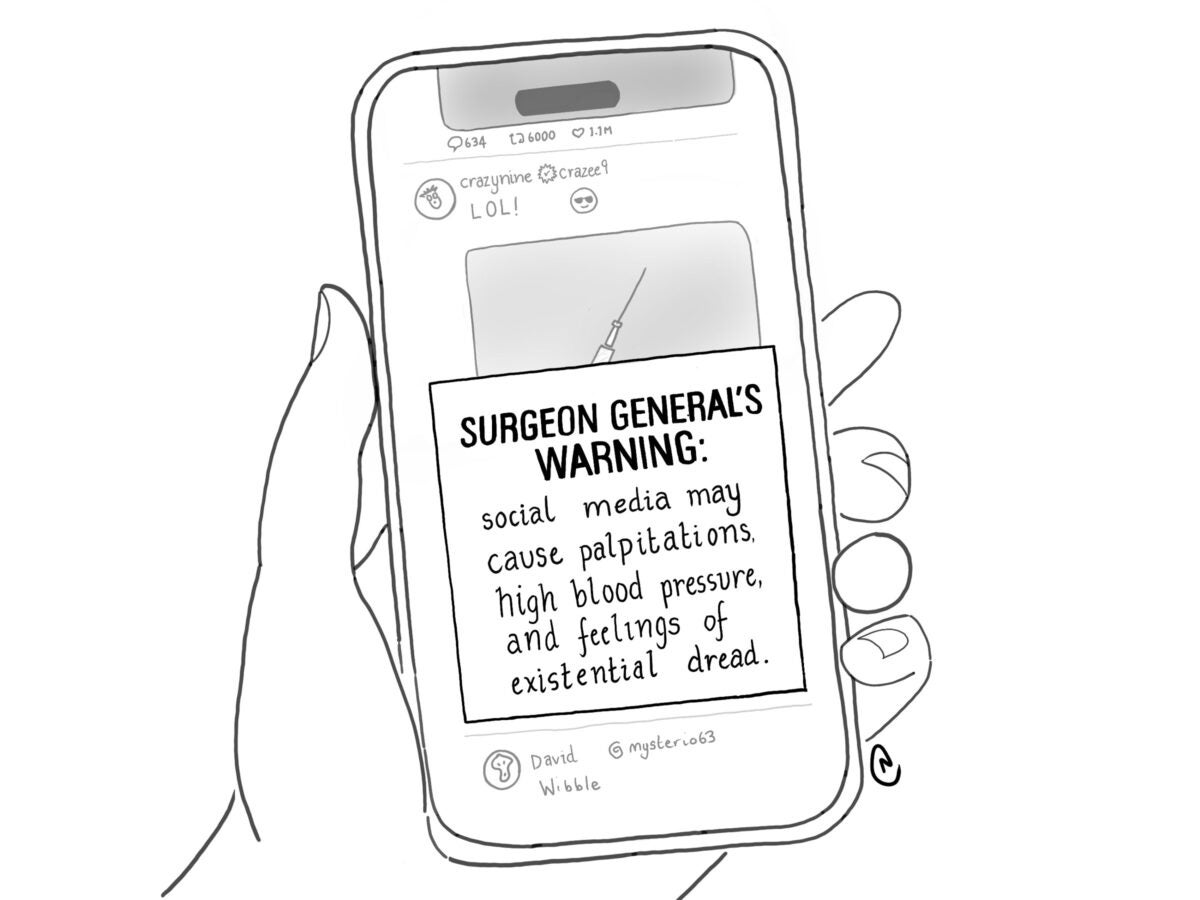

Mulheron’s advocacy comes from her own experiences after losing an infant daughter and, later, her father. She came to believe that in the United States, families and communities are losing the capacity to give bereaved people the support they need. She sees the driving factors as smartphone fixation and the monetization of death, especially through digital innovations like AI-based grief therapy apps. Besides worrying that such apps might widely share sensitive personal data, Mulheron is concerned that “you don’t talk to a counselor—you talk to your phone. I don’t think we should be going down a path where we have less human connection.” Mulheron spoke with Bill Donahue for Harvard Public Health.

This interview was edited and condensed.

Harvard Public Health: One of your interviews is with a woman who, after her son committed suicide, was treated with disrespect by the police. How does this disrespect manifest at a societal level?

Mulheron: Let’s look at how the CDC guidelines tell first responders how to handle a sudden unexpected infant death. Within hours, they ask the family to reenact the death event with a fabric doll, and they photograph everything, often while calling Child Protective Services to talk about taking the family’s other children away. This is largely intended to investigate and prevent infant homicide. But if you look at infant mortality data, infanticide is [rare]. It does happen, but why are we almost assuming that you have murdered your child?

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

HPH: You’ve also talked about the medicalization of grief.

Mulheron: Grief is now, officially speaking, a disease. If, in the wake of a death, you’re deemed maladaptive, you can be diagnosed with something called prolonged grief disorder. That “disease” was added to DSM-5 in 2022, with its own diagnostic code, and there’s a drug for it in clinical trials, Naltrexone. It’s already being used to fight addiction, so now researchers are conducting clinical trials to test if it works on prolonged grief disorder.

HPH: What’s the unifying thread here?

Mulheron: An app, a pill—these things alleviate us from having to knock on someone’s door, from sitting with them, from taking time off our phones and our video games to be with others in community for the collective good of all of us. And when you rely on an app or a pill, it feels scientific. There’s a quantifier at work, so we as a society can say, “How many protocols did we run? How many people got a script for this?” We quantify and tokenize what should be a shared human experience.

HPH: So what are you doing to make life easier for the bereaved?

Mulheron: I’ve begun talking to Capitol Hill staff about the possibility of paid bereavement leave. [Evermore doesn’t] have a lot of money, but in the field we are trying to support weeklong projects focused on helping people who’ve experienced bereavement. We did one in the South Bronx for hip hop therapy and we’re dialoguing [with] another group—this one’s in Seattle—about a project called Pongo Poetry to get people to express their grief through a modality other than [talk therapy]. We’re also working on hosting a national meeting of scientists. We want to understand the demography of bereavement. If we know the shape of the problem, we can begin to fix it.

Image: stellalevi / iStock

Clarification: This story has been updated to note that Joyal Mulheron has not testified before Congress.