Feature

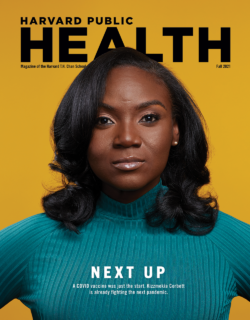

Kizzmekia Corbett is just getting started

For Kizzmekia Corbett, the last 21 months haven’t been so much a whirlwind as a tornado.

When SARS-CoV-2 emerged in late 2019, Corbett was at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases’ (NIAID) Vaccine Research Center, where she had spent six years as a research fellow and was lead on the center’s Coronavirus Vaccines Team. Few people in the world knew as much about coronaviruses—and the pandemic threat they posed—as Corbett, and she played an instrumental role in developing the Moderna vaccine. The pressure was intense, and the outcome was inspiring: The vaccine was authorized in record time and has since been administered to tens of millions of people worldwide.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Awards, congratulatory calls from world leaders, and dozens of high-profile media requests soon followed. So did an offer to lead her own lab in the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases. This June, Corbett officially joined the school as an assistant professor; she also holds an appointment at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study as a Shutzer Assistant Professor and is an associate member of the Ragon Institute of Massachusetts General Hospital, MIT, and Harvard. She plans to broadly focus her efforts on viral immunology research that can inform pandemic preparedness efforts and the development of universal vaccines.

Between moving her lab and her life from Bethesda, Maryland, to Boston, Corbett made time to talk with Harvard Public Health about the ups and downs of vaccine development, her ambitions at the Harvard Chan School, and what it was like to take over first lady Michelle Obama’s Instagram account.

Q: Let’s start by talking about how your work at the Harvard Chan School will differ from your work at NIAID.

A: While I don’t plan on paring down my research, I would certainly say that I’m going back to the basics in some regards to study fundamental viral immunology to inform vaccine development. In doing that, I’ll be broadening my horizons beyond just coronaviruses to explore other viral families. I want to do what we did with coronaviruses—create a solid body of knowledge for other viruses so that the world has information at hand to quickly and safely develop vaccines. That concept is called “pandemic preparedness,” and that’s really what my lab here will be focusing on.

Q: You’ve talked frequently about how much you have benefited from good mentors and leaders. Now that you have your own lab, what type of leadership qualities do you hope to bring to the position?

A: The most successful labs are run by people who foster an environment where everybody feels like they belong. I want my lab to feel like a family where everyone has each other’s back—there are older siblings and younger siblings, but each person has a specific position that is essential. The other thing I think is important is to lead by listening. It’s important that people not only feel as though they belong in the lab but also that their voice is heard. Oftentimes what I’ve seen, especially in bigger labs, is that younger scientists hesitate to express their opinion. Lastly, I want to be a leader that exudes grace because there is so much pressure in science, and I know as well as anyone that sometimes experiments just don’t work out.

Q: Your mentor and colleague at NIAID Barney Graham said that vaccine development involves a thousand different decisions. Are there any particular decisions that you had to make while building the Moderna vaccine that were really challenging and changed your approach to decision-making?

A: I don’t remember when it was, but I do remember one day that I had to tell my team that I just couldn’t make any more decisions that day. It felt like I was making a decision every minute, and it got overwhelming. And that’s a really important lesson that I learned from this moment—you have to know when to say, ‘OK, I’ve done everything I can do, and now I need to delegate.’ Another important lesson I learned is that you really have to trust your instincts. Because we were often making decisions about the design of experiments in real time, we could not change our minds often. And in that case, you have to trust your instincts or else you will drive yourself and your team insane.

Q: As a postdoc, you spent some time at a lab in Sri Lanka, where you studied immune responses to dengue virus. How did that experience shape your understanding of how science is done?

A: The main takeaway for me was understanding how much we take for granted in the U.S. in terms of the way we do research, the questions for which we are resourced to ask, and the ways in which we push ourselves. In Sri Lanka, I was working nights and weekends, and I wasn’t always joining my colleagues on tea breaks during the day, and people thought I was ridiculous. And yet they got their jobs done, they achieved the goals they set for their research, and they often did it really well and efficiently. I’ve been thinking about that a lot lately. We have to think about scientists as people. Doing good science requires having a rested brain and making sure that every person in a lab isn’t doing five different jobs. The other thing that struck me about my time in Sri Lanka was the diversity of the institution where I worked. I was working alongside people from all walks of life who were speaking multiple languages and had different expertise, and that had a very notable impact on how science was done and the sense of collaboration. The concept of diversity within that institution was very refreshing.

Quick hits w/ Kizzmekia Corbett

- Top three musical artists currently in rotation: Beyoncé, Jeezy, J. Cole.

- Best piece of advice from Mother: To pray for whatever I’m worried about.

- UNC or Duke basketball? Are you serious? UNC.

- First concert: Superjam. It’s a summer concert outdoors in North Carolina. My mom and dad took me and my seven siblings, and Lil’ Kim was the headliner.

- One place in the world you’ve never been but would like to visit: The Seychelles.

- One thing you can’t leave home without: A good pair of shoes.

- What will you miss most about Bethesda? My friends. And brunch culture.

Q: With regard to the idea of pandemic preparedness, what do you think the U.S. did right in terms of preparedness for COVID-19, and how can it prepare better for the next pandemic?

A: What worked really well was the level of cross-institutional collaboration that was required to make this vaccine. We had teams at the NIH (National Institutes of Health), academic institutions, private companies, and regulatory agencies aligning their efforts and coming together for the greater good. At the same time, I have to say that we got lucky. And by that, I mean that we got lucky that it was a coronavirus, because there was a subset of expertise—immunologists, virologists, epidemiologists, vaccinologists—in the coronavirus field and there were research systems and collaborations in place. We definitely would not have been as prepared if it was something like a bunyavirus or arterivirus or another family of viruses for which there just isn’t a lot of research or expertise on. And I think that is where the heavy lifting is going to have to take place. We hope that we don’t ever have another pandemic, but, frankly, we need to be developing better ways to predict what types of pathogens might emerge and prepare for them.

Q: What other pathogens do you lose sleep over?

A: I am often consumed with thoughts about other respiratory pathogens, like influenza viruses. So, sure, there are sleepless nights. But there are so many other issues—like gun violence, access to care, wealth inequity, and other social justice issues that are innately public health issues—that I don’t have expertise in that really make my mind wonder.

Q: You’ve said that vaccines are the great equalizer when it comes to addressing health disparities. Can you elaborate?

A: I should clarify that they’re a great equalizer for infectious diseases. There are obviously a lot of health disparities, and for issues like mental health, a vaccine is not the remedy. But vaccines are a medical intervention that by nature are preventive and are cost-effective. So, if we can provide a vaccine to every single person that needs one, then in theory the health disparity for that disease would largely not exist. But of course, this is caveated because there are layers of disparities around distribution and access. When I think more broadly about health disparities in the U.S., 90 percent of it boils down to access—access to care, access to insurance, and access to knowledge.

Q: You’ve talked about the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine with everyone from heads of state to strangers on the internet. Are the questions and concerns mostly the same among everyone?

A: Generally speaking, people’s questions are the same, but the way they ask them or why they ask them might be different. As an example, people might have a question about whether the vaccine is associated with infertility. One person might have the question because they saw an Instagram story about the topic, while the other person is asking it because they are suffering from infertility, and so it is a deeply personal issue for that individual. And that’s one of the reasons I felt it was important to be very forward-facing to the community and to try to answer questions on a one-to-one basis whenever possible. Everyone frames their reference differently, and so you almost have to step into that person’s shoes in order to answer their questions in a way that they hear you. The facts are the facts. But honestly, it’s not always about the facts. It’s about the way the facts are presented.

Q: It was reported that you met with players and members of the NFL’s Washington Football Team to discuss the vaccine. Can you talk about that experience?

A: There is a lot of vaccine inquisitiveness among professional athletes, and a lot of it comes from not knowing whether the vaccines are being pushed on them so they can get on the field and make a lot of money for the league and their teams’ owners. And so I just wanted to be a beacon for them and let them ask their questions in a transparent way. I don’t want to get into the details because it was a private meeting, but I spoke with the entire team virtually for an hour and it was a very open conversation.

Q: You prefer to say that people are vaccine inquisitive rather than saying they are vaccine hesitant. Why?

A: It is important to empower people to ask their questions. And I feel that when you label someone as “hesitant,” it’s almost like disregarding the fact that there is a reason why the person has decided not to get the vaccine. There are always reasons, and it’s important for us to learn those reasons so we can help address them. Of course, there are instances in which an individual has taken a stance against vaccines and that is their choice. But for the most part, a lot of people have questions about the vaccine they want answered before getting it. I found that calling this vaccine inquisitiveness allows people to be more empowered to be open about their concerns and ask the questions they want to ask.

“I want my lab to feel like a family where everyone has each other’s back—there are older siblings and younger siblings, but each person has a specific position that is essential.”

Kizzmekia Corbett

Q: You recently “took over” former first lady Michelle Obama’s Instagram account, which has more than 46 million followers. Was that fun or scary or both?

A: It was almost surreal. I haven’t wrapped my mind around it or any of these moments in the past few months because there’s just so much going on. I’ll be very honest: I think that 20 years from now, I will look back and be a little bit upset that I had to work through all of these amazing opportunities. When I was filming the Instagram videos for Michelle Obama, I had a paper due the next morning, I had to get edits back to a colleague on another paper, and I was in the process of packing and moving to Boston. In fact, my niece is with me in one of the videos about COVID-19 and teenagers. That wasn’t planned. She was there because she and my mom had come over to help me pack. So, I haven’t had a moment to just take in the fact that I was recording videos for Michelle Obama. But the world turns, and at this moment it is turning a bit chaotically. So, I guess if I have the chance to help the world turn more smoothly, I should do it and not worry about what I’m missing in the moment.

Q: What is your perspective on social media as a scientist who uses Twitter and Instagram? The platforms can be hugely influential and help get important information to people. At the same time, they can be cesspools of misinformation and disinformation.

A: I don’t really browse social media, and I’m definitely not addicted to it. Most of the time when I hear about a new vaccine rumor, it’s because someone is text-messaging me about what they saw on Twitter or Facebook. But I do think it’s important to have a presence, and I especially thought so when I was an employee of the federal government. I actually put an hour on my calendar every single day so that I could answer every single direct message people sent to me.

Q: Wow. That’s amazing and possibly terrifying depending on the message. Why would you do that?

A: I held a taxpayer-funded public service position and it felt like my duty to respond. The people who would take the time to send me a note on Twitter or ask me a question are not the same people who are writing letters to the White House or to Dr. Fauci. These are ordinary people who can often feel like their questions and concerns are ignored by people in power, especially when it comes to questions about their health. I wasn’t going to be another person who ignored them, so I made it my duty to respond. Once in a while, I would get people intentionally being mean and I would respond, and they would say, “Why don’t you block me?” and I would explain that as a public servant, I don’t block anyone—and most of the time, they would come around. We have seen how scientists and health care workers have used social media effectively throughout the pandemic to make their voices heard and become trusted sources of information. I really hope the conversation continues to move forward in that direction because it is important for people to know that there are real people behind the science.