People

Jimmy Carter’s decades-long crusade against a forgotten disease: Guinea worm

Barack Obama’s Kenyan roots make him the American president we Kenyans are most proud of, but the one we are most thankful for is Jimmy Carter.

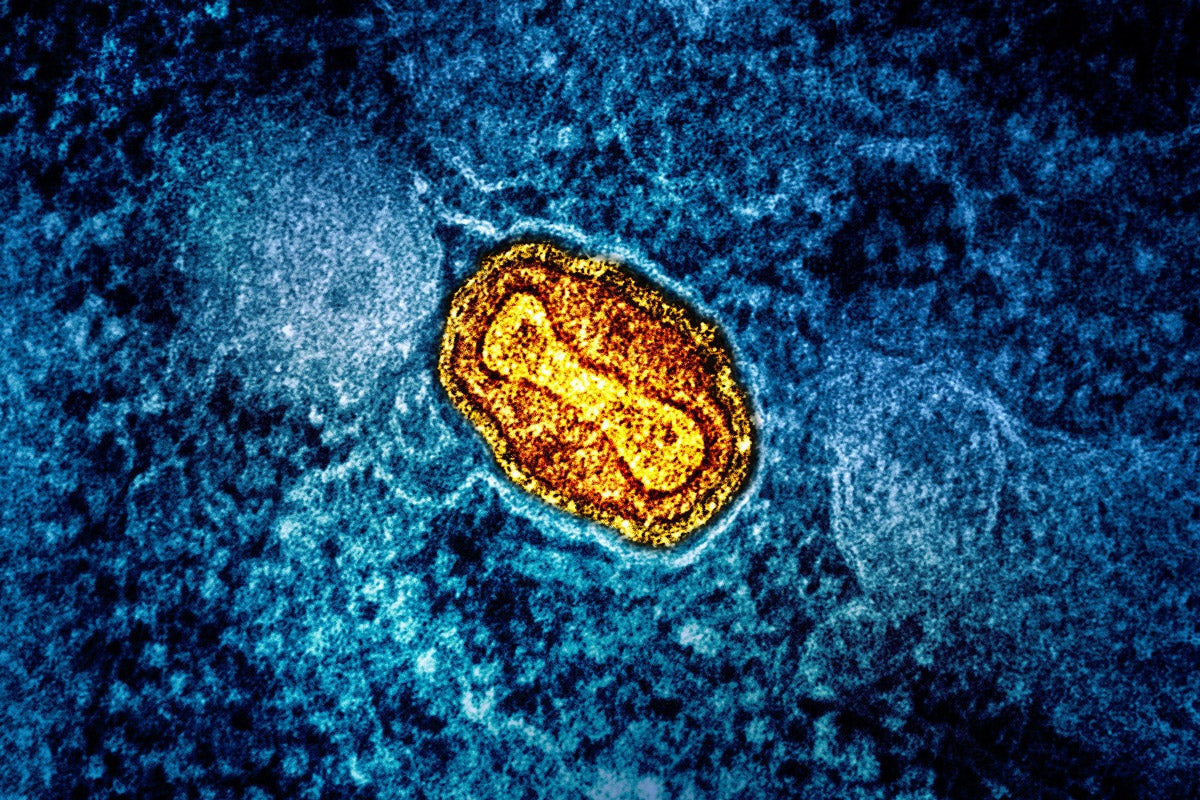

Carter helped rid Kenya of Guinea worm disease (dracunculus medinensis), a rarely fatal but gruesome condition caused by the parasitical Guinea worm, which can grow up to three feet long inside the body. The skin lesions the worm creates are so debilitating that infected people can miss school or work for up to two months.

Carter prodded governments and large NGOs for decades to pay attention to Guinea worm and other neglected tropical diseases. Because of these efforts, Guinea worm is on the verge of being just the second infectious disease eliminated from the planet, after smallpox. There were only 13 cases of Guinea worm in humans recorded last year (40 years ago, there were 3.5 million). In Kenya, where the disease was eradicated five years ago, health officials say the success has freed up resources for combatting other diseases.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Advocates praised Carter for changing the dynamic around neglected tropical diseases. “These diseases affect the marginalized, the poorest of the poor who live in abject poverty and in war-torn areas,” says Monique Wasunna, the eastern Africa director for the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative. All told, 1.7 billion people are afflicted by neglected tropical diseases, 40 percent of them in Africa, and disproportionately women and children. Despite the vast numbers affected, these diseases have not been given funding priority by governments or aid groups, and drugmakers remain deterred by the poverty of those making up much of the potential market. As Wasunna says, “Pharmaceutical companies do not want to develop drugs for people who may not buy.”

But Carter was undeterred. For Guinea worm, the Carter Center worked to map the disease’s prevalence in affected countries through surveillance. Then the Carter team created programs to educate communities about the risk of infection—the disease spreads primarily through contaminated water—and how they could prevent it by filtering water drawn from open sources or drilling boreholes, which have little risk of contamination.

These simple but powerful steps have led to a 99 percent reduction in Guinea worm cases, and to its eradication in many countries, most recently the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Carter Center’s approach has become a template for addressing such diseases, says Jordan Tappero, deputy director of neglected tropical diseases at the Gates Foundation, a Carter Center funder. Active cases in people exist in just a few countries including—Chad, Ethiopia, the Central African Republic, and South Sudan. A number of these countries have or are experiencing internal armed conflicts.

Conflict is always an impediment to fighting diseases, but here, too, Carter helped create breakthroughs. He negotiated a four-month ceasefire in 1994 in Sudan in order to allow health workers to travel to remote villages and engage in Guinea worm disease education efforts while also supplying villagers with water filters — which led, the following year, to the establishment of an eradication program in the country.

Read next

AI is already tracking the next pandemic

Breakthroughs ahead from African labs

The fall of global health’s benevolent dictatorships

Eliminating Guinea worm has taken longer than expected, and even with so few cases in humans, the target date for full eradication is now 2030. Adam Weiss, director of the Carter Center’s Guinea Worm Eradication Program, says among the challenges are research questions. “Do we fully understand the genomics [of the worm]? Have we fully explored all the public health requirements for eradication of NTDs?” Such requirements are still changing, decades into the fight—one recent approach developed in Ethiopia involves tethering domestic animals to reduce potential contact with infected animals. Still, Weiss is optimistic that Guinea worm may be eliminated several years early. Carter had hoped he would outlive the worm he started fighting in 1986, the year the Carter Center at Emory University opened as part of Carter’s presidential library complex in Atlanta, Georgia.

Carter’s focus on neglected diseases fostered the idea of health care as a human right, especially for poor and marginalized communities. Carter also wanted to eliminate lymphatic filariasis, malaria, river blindness, schistosomiasis, and trachoma in his lifetime. And while he did not fully succeed, the fight has been a valiant one. Even in the face of setbacks, such as when the discovery of Guinea worm in pet dogs and other animals meant that the risk of human infections remained, Carter emphasized diligence and resilience. “He encouraged us to carry on,” says Tappero, who cites Carter’s steadiness as a spark for the Gate Foundation redoubling its own efforts to fight Guinea worm as well as other neglected diseases, such as lymphatic filariasis in Haiti. The Carter Center also urged better animal surveillance, including through a partnership between the World Health Organization and local health ministries.

Despite Carter’s success, neglected tropical diseases still don’t attract much investment for diagnostics, prevention, or new treatments. What treatments do exist, Wasunna notes, can be long and demanding, sometimes even creating physical disabilities, which in turn add mental health stress for patients. She would like to see simplified, shorter clinical trials to help foster a new drug research.

Fighting neglected diseases is just a piece of Carter’s impact on global health. The Carter Center works just as diligently to improve maternal and child health, address mental health in crisis-afflicted countries, and increase access to better housing for the poor. His insistence on better health for all people has shifted the dynamic of combating disease globally and expanded the world’s global health arsenal. That will be his major legacy.

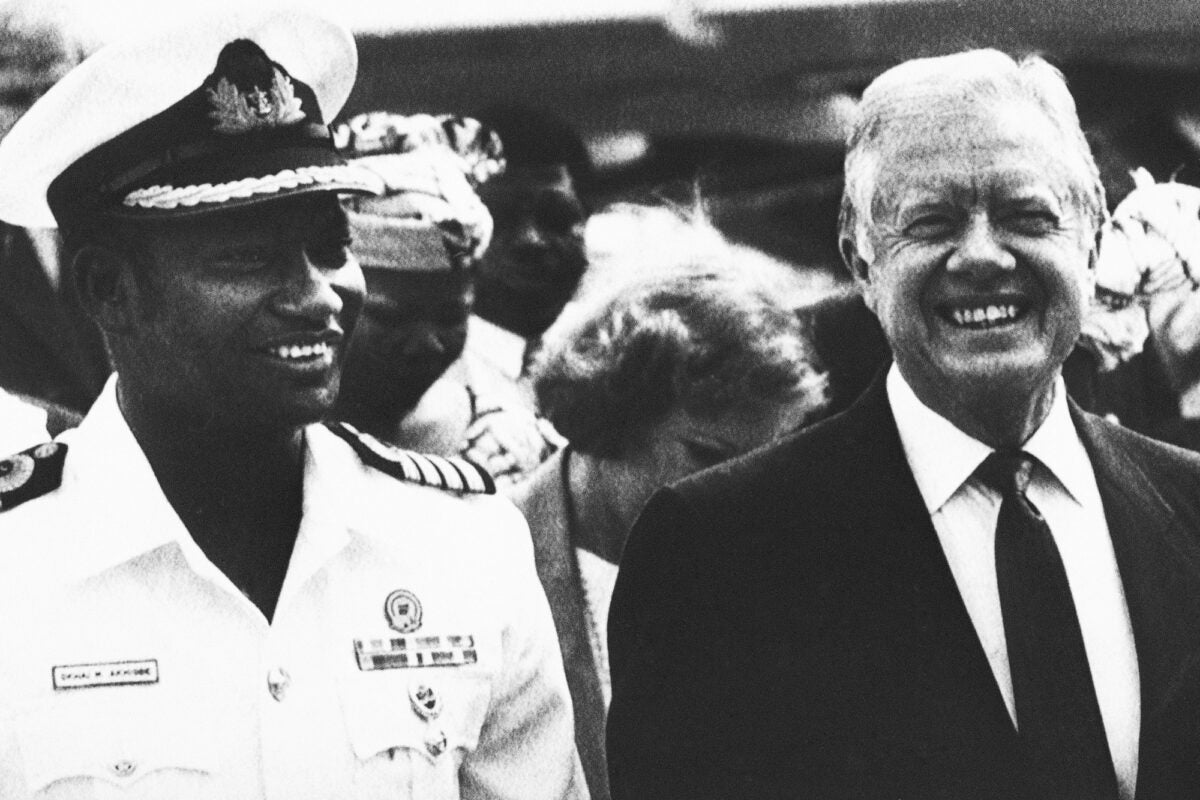

Top Image: Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter visits Lagos, Nigeria in 1988, the first stop on a tour of several African countries. Carter, shown with the governor of Lagos State, Capt. Mike Ahigbe, pledged to eradicate guinea worm. Credit: AP Photo.