Opinion

A new model of drug discovery could change the game on superbugs

A growing scourge of superbugs poses a grave threat to global health. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) contributes to nearly five million deaths annually and could result in more than $1 trillion in economic losses globally, every year, by the end of this decade. Bacteria are developing resistance to the most powerful antibiotics, and existing drugs could become obsolete.

But a nontraditional model of drug discovery and development could change the game. Already, the model is working against one of the most notorious AMR offenders—Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which causes tuberculosis (TB). This unconventional drug discovery model has the potential to help accelerate the fight against other disease threats.

Developing new drugs can be expensive, often costing more than $1 billion from discovery to regulatory approval. When for-profit private developers balance the cost of this investment against the likely market for TB drugs, the math doesn’t add up. Although TB last year killed 1.3 million people, the disease disproportionately affects low-and middle-income countries (LMIC), and TB patients often cannot afford to pay high prices for treatment.

This market conundrum is not unusual for other priority AMR pathogens, like Klebsiella pneumoniae and E. coli: Although these bacteria impact populations in rich and poor countries alike, the overall population suffering from these resistant infections is not large enough to translate into a broad market for new drugs. Additionally, the current global norm on AMR, set by the World Health Organization, is that novel products targeting multi-drug resistant infections need to be used sparingly to avoid generating additional resistance. In these conditions, pharmaceutical companies have been uninterested in prioritizing new drugs against antibiotic resistant bacteria.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

A collaborative model for success

Global multi-sectoral partnerships, such as the TB Drug Accelerator (TBDA), provide a solution to this market failure by bringing multiple companies together to drive forward research and development. Established in 2012, the TBDA is now a 26-member consortium spanning eight countries. Members share compound libraries and datasets to accelerate drug discovery—sharing that has contributed to the most promising pipeline of new TB drugs in history, including for multi-drug resistant forms of the disease, which killed 160,000 people last year.

While traditional drug development relies on one company to shepherd a drug from discovery to approval, the accelerator brings together multiple independent companies and organizations. Unburdened by traditional competition, the TBDA encourages risk-sharing, communal credit, and shared goodwill. Imagine a scenario where one partner discovers a promising compound but is not set up to conduct efficacy studies: The work is seamlessly handed off to another partner who is.

The architecture of the consortium also responds to a unique characteristic of TB. To achieve complete cure and avoid the emergence of resistance, TB drugs need to be tested in combinations, which is hard for any single partner to do. A shared portfolio approach enables multiple companies to pool their compounds for joint testing. This approach, fueled by in-kind support from pharmaceutical partners and philanthropic funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, lowers development costs by sharing research infrastructure and expertise.

Equity is a fundamental part of this approach. Participating in the consortium requires a formal commitment that any products derived from the program will be accessible at an affordable price in LMICs. The consortium also includes research teams based in high-burden countries, and it engages with communities broadly to ensure that products meet their needs and can be easily delivered to patients in resource-poor settings.

Today, the clinical pipeline for new TB treatments includes eight candidates from the accelerator alone. There are also efforts to develop a first-line treatment that would work against all forms of pulmonary TB, regardless of resistance. It’s a target that has eluded researchers since drug resistance first emerged, and now at least two potential regimens are in a clinical trial, led by a consortium with a similar ethos of cooperation.

Opportunity ahead

The accelerator model has driven rapid drug development and can be used to target other drug-resistant pathogens. Augmenting this model with cutting-edge AI and modelling tools can help focus on drugs and drug combinations that have a lower likelihood of selecting for resistant bacteria. And integrating equity and access principles from the start—by involving affected communities and local experts from high-burden countries in shaping research agendas and building responsive regulatory systems—ensures innovation will reach those who need it most.

By championing productive partnerships, prioritizing equity, and driving political and financial firepower, we can stop the needless deaths related to AMR.

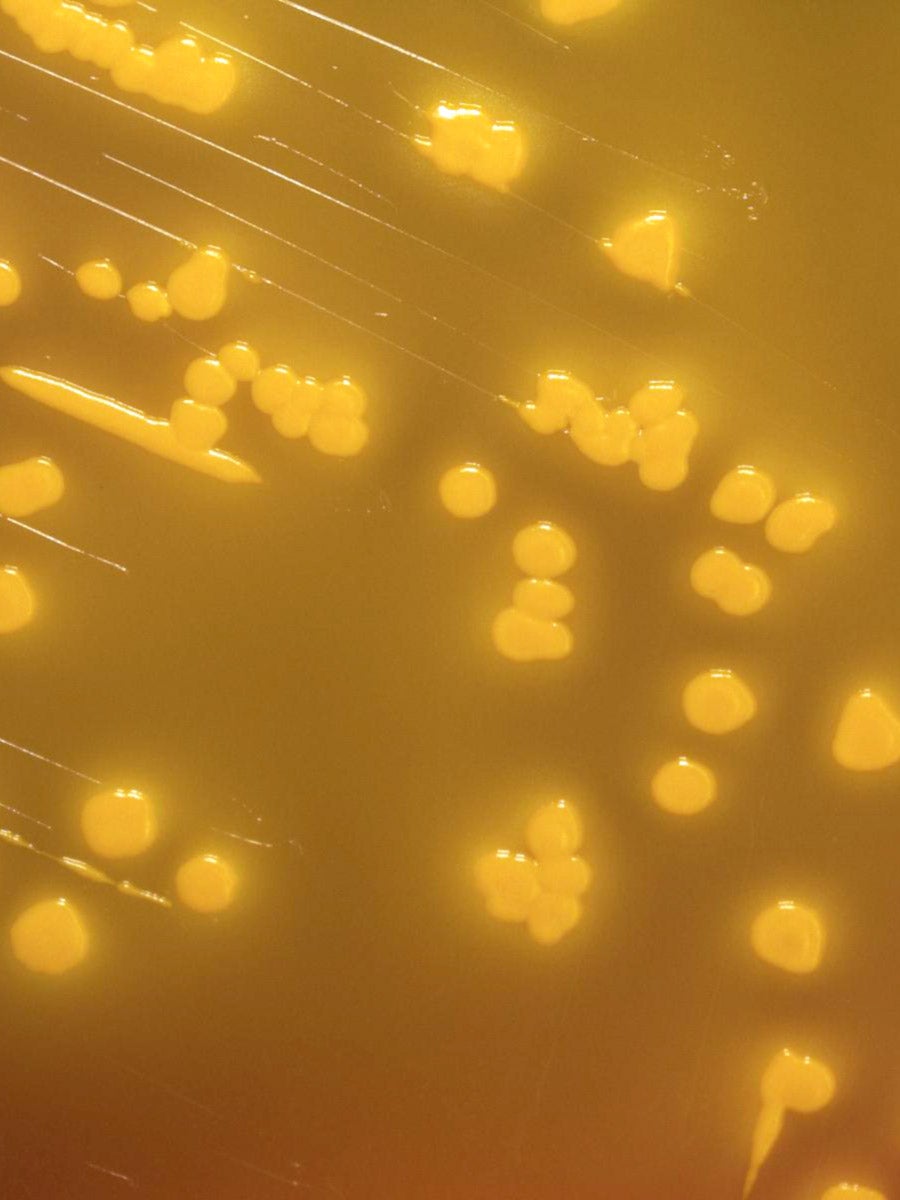

Lead image: The Yersinia pseudotuberculosis bacteria, viewed under a powerful microscope after being cultured for two days. (CDC / Public Health Image Library)