Feature

The ‘Black Angels’ who helped cure tuberculosis

This article was originally published by The Emancipator.

The exodus of White nurses began in spring 1929, months before the stock market crash. Without warning, they hung up their uniforms and walked out of Sea View Hospital, New York’s largest municipal sanatorium. Their reasons for leaving varied. Some blamed the 14-hour shifts and five-hour round-trip commute from Manhattan to Staten Island, where the hospital was located. Others blamed the emotional and mental toll the job demanded, caring for the city’s indigent consumptives who lay in its wards, dying of tuberculosis.

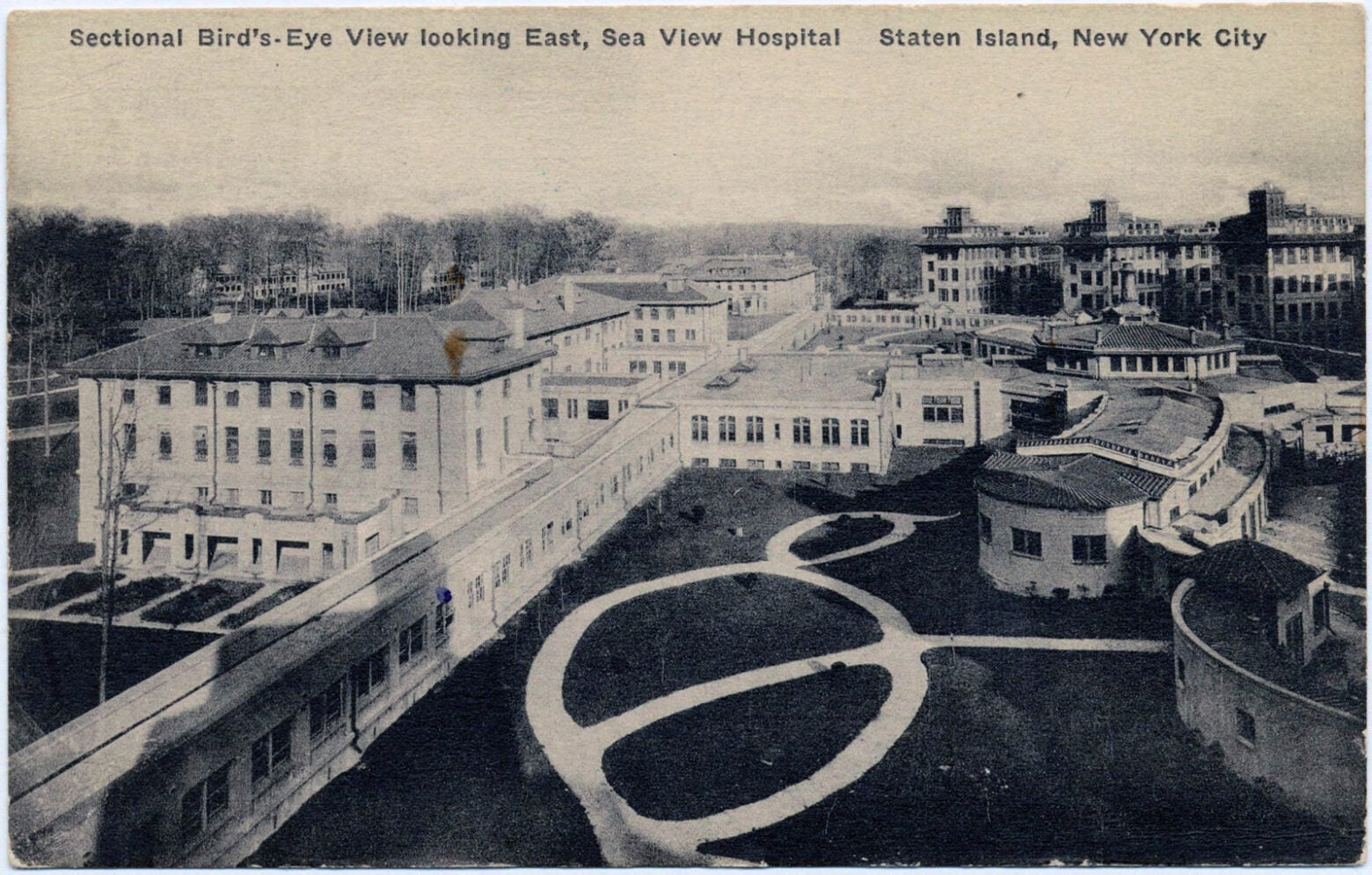

Nicknamed the “Pest House,” Sea View sat on an isolated hilltop 400 feet above sea level, overlooking New York’s lower bay where it spills into the North Atlantic. Sprawling across 300 acres, the complex boasted dozens of buildings, including two chapels, a synagogue, a morgue, a theater, a nurse’s residence and eight austere five-story pavilions that seemed to rear against the sky. Inside, almost a thousand patients lay in open wards, languishing as millions of microbes gnawed at their tissues, organs, and bones. All day, patients struggled to breathe, as long-lasting coughing fits often cracked their ribs, causing them to choke and gag and send swarms of live germs into the air. The bacteria settled onto bedpans, nightstands, bed frames, and nurse’s carts. It floated under beds and down hallways, sneaking into every corner of the ward.

For years, the White nurses had watched their colleagues grow ill. They saw their faces turn ashen and their eyes glisten from a fever that sent the mercury soaring, causing drenching sweats and wild hallucinations. Some recovered, but others died in the wards where they once worked. Wanting to avoid the same fate and knowing they had plenty of options for jobs that wouldn’t kill them—stenographers, secretaries, librarians, salesclerks—the nurses began quitting, abandoning Sea View, their patients, and the disease that had dogged New York City for decades.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

The plague of New York City

Beginning in the early 1900s, tuberculosis spread throughout the city, finding willing hosts in the waves of European immigrants who arrived daily. Stepping off the ships with their suitcases and bundles, many headed to Manhattan’s Lower East Side, where nearly 80,000 five-story tenement buildings collectively housed 2.3 million people, almost two-thirds of New York’s population. Sometimes, entire generations lived inside these buildings, which were described as “fever breeding structures” by photojournalist Jacob Riis. The families lived and worked in 300-square-foot apartments with scant fresh air and sunlight.

City officials like Dr. Hermann Biggs, the general medical officer for New York City, despised these buildings and the people who lived in them. For years, Biggs tried to control the spread of tuberculosis through a series of public health measures: disease maps, registration laws, tent colonies, mass mailings, posters, and even a “health clown” who sang health ditties to children living in the slums. But nothing stopped the disease from spreading.

When Sea View opened in 1913, it was the largest and most expensive complex in the country for the treatment of tuberculosis.

The New York Public Library

In the 1920s, Black nurses could only work in Black hospitals. America had approximately 260 Black hospitals, compared to over 6,000 White ones.

Biggs grew desperate and turned to city officials, imploring them to build a hospital as a “necessary protection for those who don’t have TB but are exposed to it by the carelessness of others.” The city obliged and opened Sea View in 1913; within days, it reached its capacity of 800 patients. By 1920, the hospital had helped lower New York’s annual death rate from 10,000 to a little more than 5,000. But there it stalled, turning Sea View’s triumph into the city’s nightmare.

Tuberculosis was the third-leading killer in New York and the fourth globally. If officials couldn’t restaff the wards, they would be forced to close them, releasing hundreds of highly contagious patients into the city. Infection rates would rise, and decades of progress would be reversed. New nurses had to be found—immediately.

The great migration of Black nurses

Health officials and infectious disease experts scrambled to replace the White nurses, holding emergency meetings. Soon, an idea emerged. Labor recruiters had successfully enticed Black sharecroppers and farmers to come north and work in their slaughterhouses, steel mills, kitchens, and factories. Despite the intensity of the labor, for many, it was a small price to pay for a steady, well-paying job and freedom from the constraints of Jim Crow. “I make $75 per month. I … don’t have to mister every little white boy that comes along,” wrote one migrant in a letter. Given the success in luring laborers and domestics, there was no reason a similar tactic wouldn’t work for professional Black women in nursing.

Across the South, hundreds of trained Black nurses remained unemployed because the same country that drew lines around water fountains, bus stations, and waiting rooms also drew them around hospitals. At the time, Black nurses could only work in Black hospitals, and in the 1920s, America had approximately 260 Black hospitals, compared to over 6,000 White ones. If a White hospital did hire Black nurses, the White supervisors often delighted in verbally and emotionally abusing them. In Alabama, the director of public health believed that Black nurses had “limited intellectual capacity,” making them “incapable of abstract thinking.” In Atlanta, the superintendent for Grady Hospital declared they had “no morals, and unless they are constantly watched, they will steal anything in sight.”

To lure the nurses north, the city would offer them a package deal: free schooling at Harlem Hospital School of Nursing, on‑the-job training, housing, a salary, and—above all as they saw it—a “rare opportunity” to work at one of the city’s integrated municipal hospitals. Only four of New York’s 29 hospitals employed Black nurses at the time.

During the 1930s and 1940s, hundreds of nurses answered the call. Eager to live free from the daily constraints of segregation—the back doors, the “yes, sirs,” the colored fountains, the waiting areas—they packed up their lives and left southern cities and rural towns. Alongside the laborers, these often-overlooked professional women boarded Jim Crow trains and buses, their nurses’ whites tucked into suitcases atop Bibles and photographs, and settled in for the long trip north.

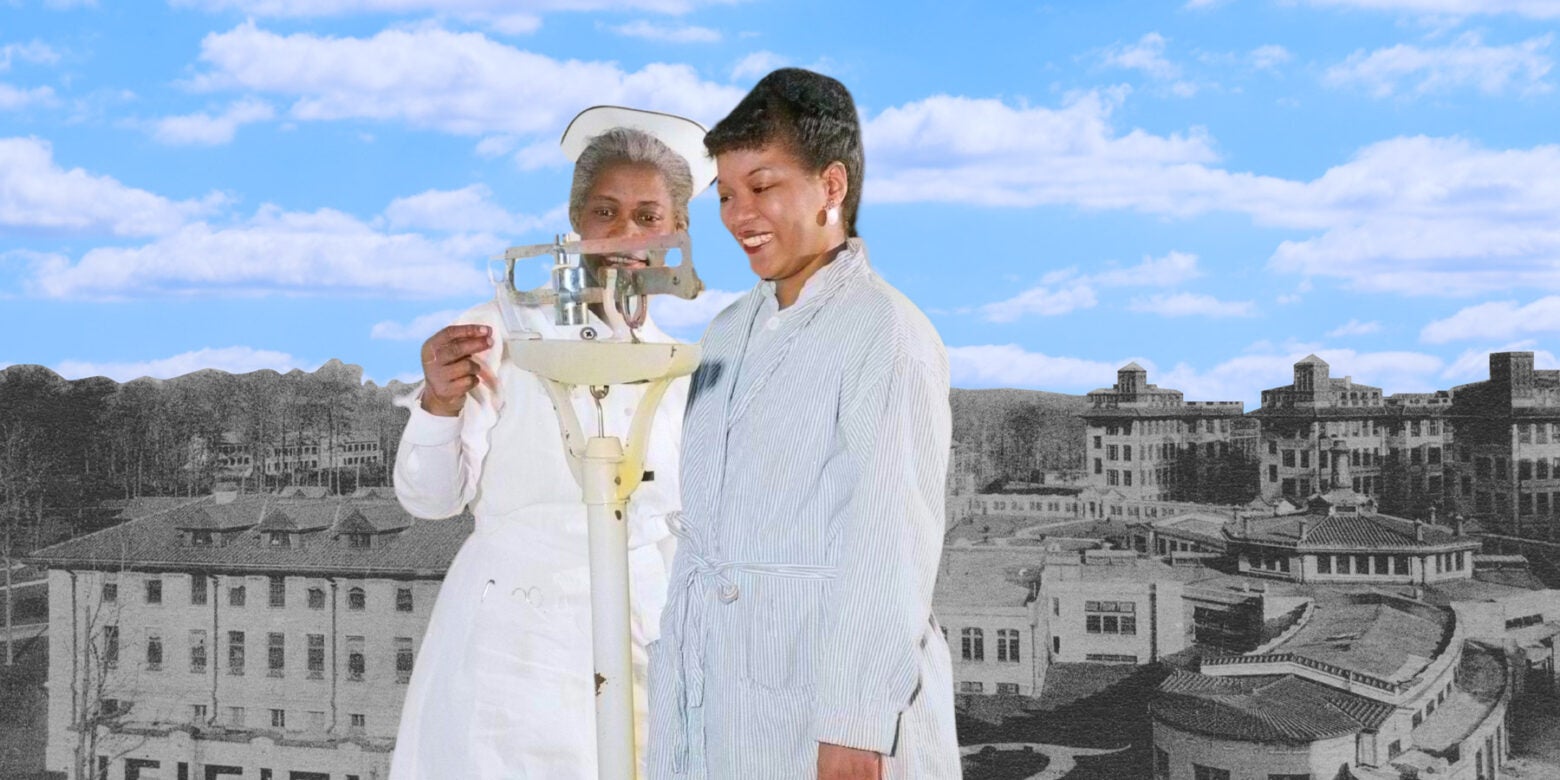

Top row: Jane Shirley; Bessie, a charge nurse; Curlene Jennings. Bottom row: Phyllis Alfreda Hall, Salaria Kea, Virginia Lee Greene.

The Emancipator / The Shirley family, Greene family, the Bennett family, the Allen family, and the Sea View archives.

On one of those trains sat Missouria Louvinia Walker-Meadows, fresh from Howard University and determined to put down new roots and fight against inequality. Kate Gillespie also came, fleeing Alabama with her young son to spare him, her family said, “from seeing the strange fruit growing on trees,” as did nurses Nellie Mae Holmes and Leola Washington.

Then there was 28-year-old Edna Sutton from Savannah, Georgia. Born in 1900 on the floor of a tar-paper shack in one of Savannah’s shantytowns, Sutton dreamed of becoming a surgeon, an aspiration many believed was impossible for a Black woman. But her father, an enslaved man, had inspired his daughter after he walked off his plantation in Wilkes County, Georgia in 1899 to arrive in Savannah, where he reinvented himself and became a preacher. He had taught her to dream big, so after high school, she enrolled in one of Savannah’s two Black training schools for nurses.

Despite the long hours, the difficulty of the work and the lack of supplies—many times, there weren’t enough shrouds to bury the dead—Sutton loved her job. In the words of her family, she had “found her calling.” But after two years of training, the school let her go. Unable to find a nursing job, she worked as a clerk, where she spent years sorting and stapling papers and caring for her younger sister.

What Sutton wanted most in her life was a professional career, a job that would allow her to pursue her dream of medicine and make her enough money to buy a house in a place where she didn’t have to look at signs telling her where she could sit, walk, and go to school. A place where her younger sister would have opportunities that she could only ever imagine. Sea View, she believed, could be that place. She applied in August 1929 and was accepted.

Upon arriving, Sutton joined hundreds of other nurses who were relegated to the woefully understaffed and underfunded municipal hospital, where they all found people who were sicker than anyone should be allowed to become. Working 16-hour shifts in the surgical wards, she listened to patients who asked about the operations with terrifying names—thoracoplasty, lobectomy, phrenic nerve crush—and then tried to quell their anxiety about dying.

The nurses fought redlining by hiring lawyers and enlisting the NAACP to help them buy the homes they wanted on the streets they desired in Staten Island.

The long road to a “wonder drug”

The nurses also dealt with racism inside the institution, personified by their supervisor, Lorna Doone Mitchell, a Teutonic White woman and the daughter of a Confederate medic, who wielded her power in perverse ways. She lurked in hallways, hoping to catch the nurses doing something wrong; refused requests for transfers; and prevented them from wearing masks on a regular basis. Masks, she said, made them “complacent.” Then there was the president of hospitals, a man who held the racist vision that Black nurses were expendable. At a meeting in 1933, he was asked why the city sent Black nurses to Sea View. “Because in 20 years,” he said, “we won’t have a colored problem in America because they’ll all be dead from TB.”

However, they didn’t die. Instead, the nurses relied on their professional status and know-how to band together, organize and fight for equality by creating petitions and policies that helped to desegregate the New York City hospital system. On a national level, they joined nurse leaders Estelle Massey Osborne and Mabel Keaton Staupers to advocate for integrating Black nurses into the American Nurses Association. They brought that same spirit home to Staten Island, fighting redlining by hiring lawyers and enlisting the NAACP to help them buy the homes they wanted on the streets they desired. They proceeded to build a middle-class community and represent Black America as career-driven homeowners.

But mostly, the Black nurses of Sea View uplifted the industry they were called to serve by broadening human rights and caring for a patient population who, like them, was seen as disposable. In doing so, they became experts at their jobs. In 1951, Dr. Edward Robitzek trusted Sea View’s nurses to oversee the first human trials of isoniazid to see if it could prevent the spread of tuberculosis bacteria, referred to by one journalist as “the most grandiose experiment ever undertaken in the history of medicine.” Their work on those trials led to the February 20, 1952 announcement where the New York Post prematurely broke the news about a cure with the banner headline, “Wonder Drug Fights TB.” In a single galvanizing moment, the course of history was altered. It was triumphant, and as Robitzek later said, “none of it would have been possible without the nurses.”

In a photograph taken that day, the once-incurable TB patients jitterbugged front and center. In the back stand the Black nurses, their faces staid and somber. Their experience tells a more complex story, one of the women who saw terrible things; who did the impossible by prevailing over one of humanity’s greatest scourges; who followed orders from physicians who themselves were at a loss; who worked through trial and error, sometimes prescribing unreliable medications that often made people sicker; who stood in surgical rooms watching operations turned to butchery.

They did it because it was their job; because they were professionals who had committed themselves to saving lives at the risk of their own. But, also, because they were Black women, subjects of Jim Crow labor laws that offered them two options: stay in the South and dream of becoming a professional, or rise and join the Great Migration and actually become one. These women, whom patients came to call the Black Angels, chose the latter.

No one can deny that after COVID-19, the next public health crisis will come. Once again, the most vulnerable, ambitious, and aspirational among us will be called and tasked with working tirelessly to keep Americans safe and their patchwork of a health care system from completely coming undone. And if we keep asking nurses like the Black Angels to bear this impossible burden—all while being undervalued and underpaid—then the next crisis just might be our last.

Lead image: The Emancipator / Getty Images