Ideas

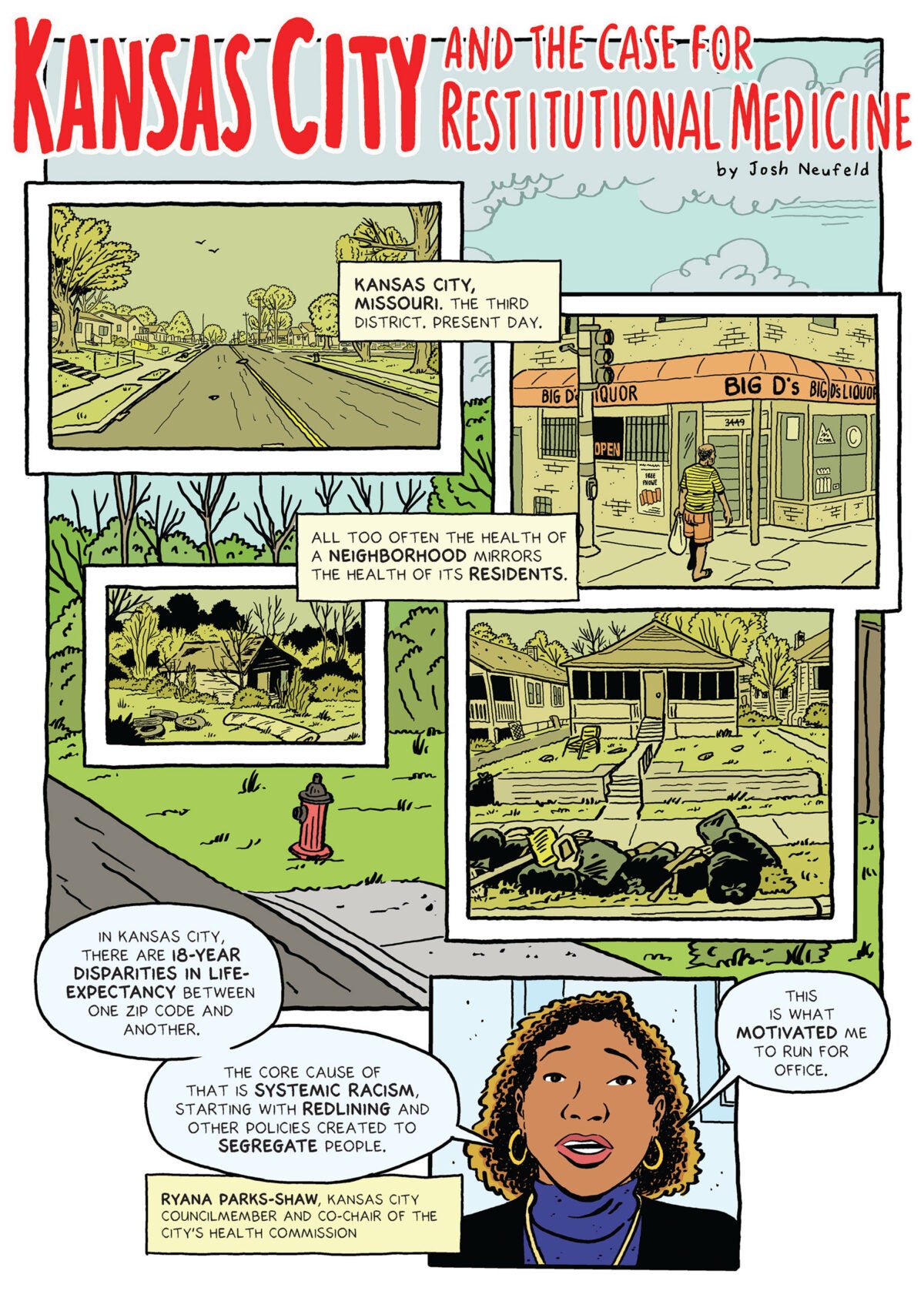

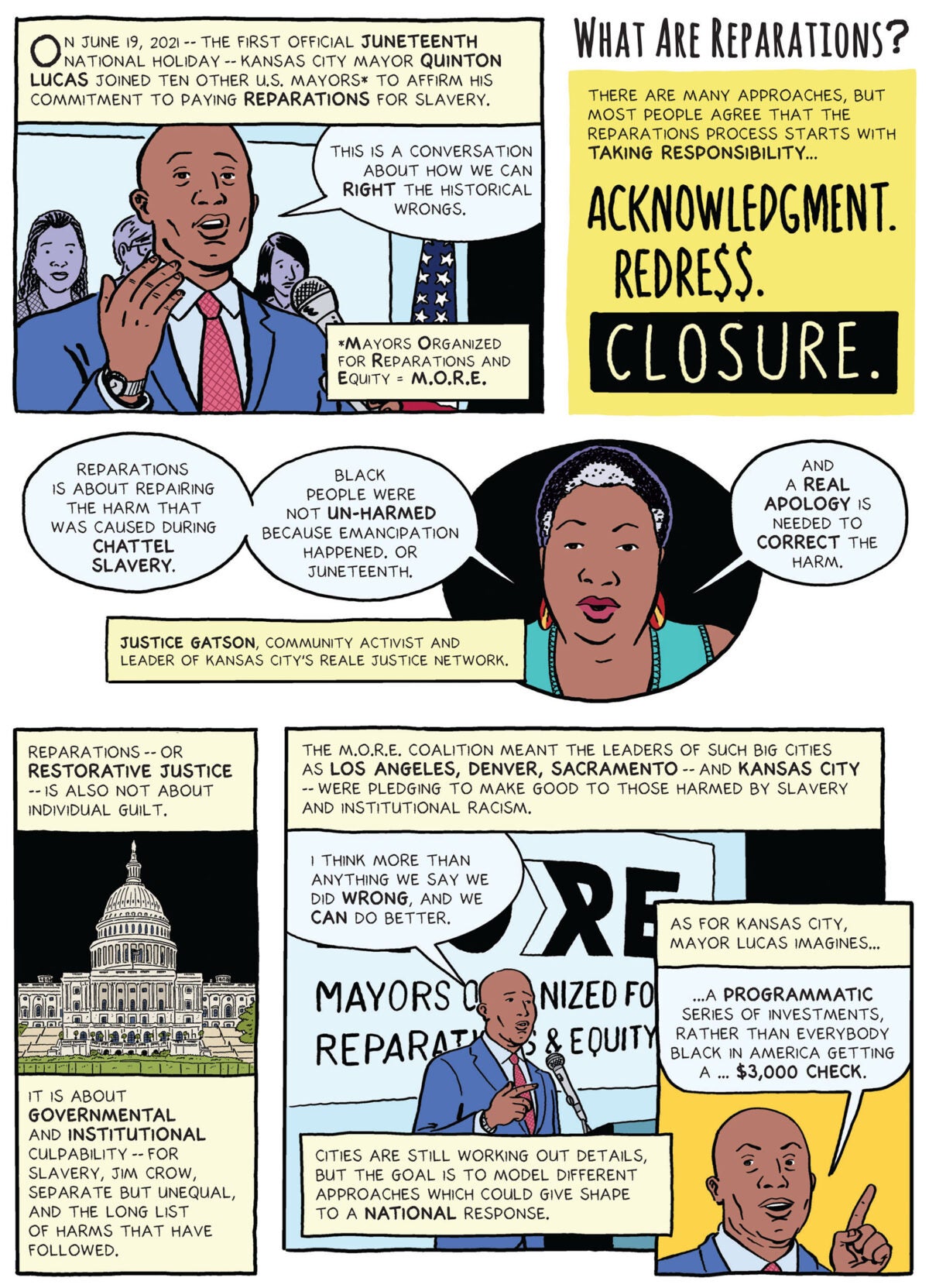

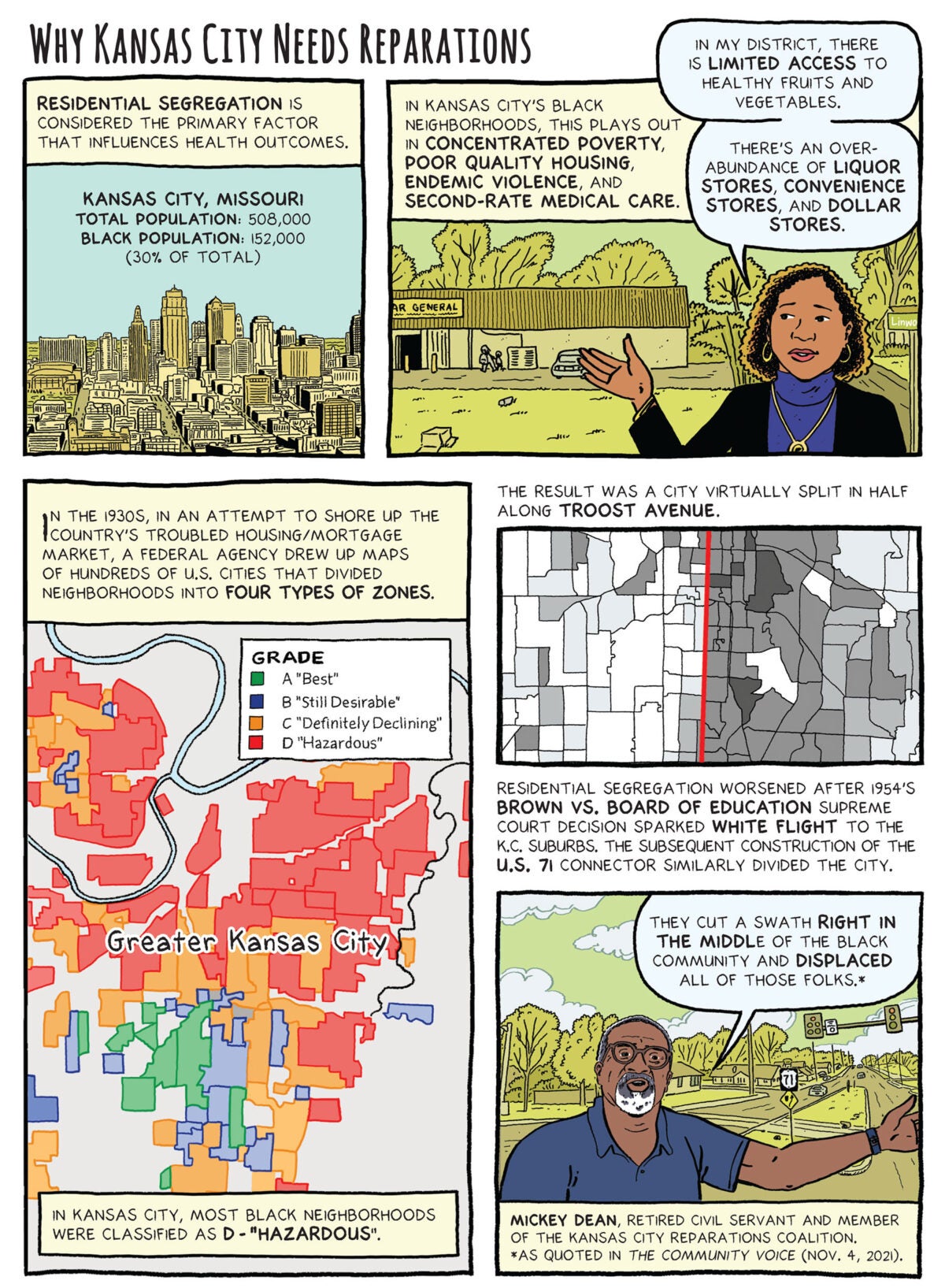

Kansas City and the case for restitutional medicine

How one U.S. city is looking at using reparations to redress structural racism and boost community health outcomes.

![Image three: Top panel: The word RACISM is visualized as giant, heavy, rocky letters, crushing silhouettes of people who are trying to hold them up. Text box reads: So can reparations be connected to health? The answer is yes. For one thing, numerous studies show that disease and death rates are elevated for marginalized racial and ethnic groups. Illustrations of scholars Derek Ross Soled, Avik Chatterjee, Daniele Olveczky, and Edwin G. Lindo, above a text box that reads: It’s well-established that there are health costs from just “being Black” in America. In a 2021 paper published in Frontiers in Public Health, the authors state (dialog box depicts them saying in unison): “When adjusting for other sociodemographic factors, being Black is independently associated with increased incidence of [a variety of] mental health conditions...Middle panel: Illustration of the silhouette of a Black man in a depressed pose (head in hands, stress emanates) surrounded by the words anxiety, depression, hypertension. Text box reads: “Research shows that they are not due to innate biological differences, but rather influences of chronic and unremitting stress caused by racism.”…Bottom panel: Text box reads: Compounding the issue, our country’s history of racist medical practices is long and calamitous, including pernicious ideas like Black people having a higher tolerance for pain, or being more resistant to certain diseases. Not to mention being FORCED into experiments during slavery. Illustration on left shows a white researcher drawing blood from a rural Black man in the Tuskegee syphilis study as another rural Black man with a sad expression watches. Illustration on right shows of an enslaved slave woman named Lucy kneeling on a table, as J. Marion Sims, a pioneering gynecologist in the 19th century, and two other white men stand around her. Two other slave women peer nervously from behind a nearby curtain…. Below is an illustration of Justice Gatson superimposed over an image of Henrietta Lacks’ HeLa immortal cells. Gatson says: “Or you talk about Henrietta Lacks and what her cells did for medical research. And yet her own family was denied what her cells did.”…](https://harvardpublichealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/HarvardPublicHealth_KansasCity_reparations-03-1200x1661.jpg)

![Image eight: Top left panel: Illustration of Mayor Lucas in blue suit and red tie in a meeting room with Justice Gatson and other Black community leaders. Lucas’s is standing while the rest of the group sits around him. His hands rest in an inquisitive gesture[FM1] . He says “How do I put this package together — how do I disburse it?" Top right panel: Justice Gatson waves her right hand and says “If we have this coalition together by the beginning of the fall, I will feel like our Mayor is very sincere. I don’t think he’s stringing us along. Because if he is, a lot of groups will come for him.” Middle panel: Text box reads “One hopeful sign for reparations happened this past summer, when the city won a $5 million grant to plan ways to restore Black neighborhoods severed by Highway 71.” Illustration of Mayor Lucas at an intersection, in front of several other men and women in official-looking dark suits. Speaking into a reporter’s microphone, Lucas, who is holding up his right hand, index finger pointed at the sky, says “You can’t go back to the past, but you can try to do better.” Bottom panel: Text box says: “That may not seem directly related to restitutional medicine, but healing a broken community sparks the imagination. Illustration in softer tones of what the Kansas City neighborhood from the start of the story might look like after reparations: a farmer’s market with fresh produce, Black families and couples, including a man in a Kansas City Royals baseball cap, examining fresh apples, clean streets and sidewalks, and in the background various people out and about. The liquor store is imagined as being replaced by a maternal health clinic next to a market. Inset illustration of Gatson, arms crossed, looking determined. She says “We know what we need, but there’s a huge gap. Reparations are in order.” Text box reads: “Never the end.”](https://harvardpublichealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/HarvardPublicHealth_KansasCity_reparations-08-1200x1656.jpg)

The illustration on the third page depicting J. Marion Sims and Lucy, an enslaved woman, was modeled after the painting Marion Sims: Gynecologic Surgeon, circa 1952, from Great Moments in Medicine by Robert Thom. This illustration and that of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment originally appeared in “A Tale of Two Pandemics” in The Journalist’s Resource.

Contributors

Josh Neufeld

Josh Neufeld is a comics journalist based in New York.

From the Issue