People

Showing up for the underserved

Linette didn’t plan on getting vaccinated that day in early June. She came out to Family Day—an annual block party in San Francisco’s Sunnydale neighborhood—to groove to the DJs blasting hip-hop and devour tantalizing tacos. The sparkling car show and the mechanical bull both begged attention, while thousands of neighbors chatted nearby. It was party time, and the last thing on her mind was a COVID-19 vaccine.

Sunnydale, along with nearby Bayview Hunters Point, is home to much of the city’s dwindling Black population and while Sunnydale boasts strong community pride, it’s been historically underserved. When COVID-19 hit San Francisco last year, Sunnydale became an epicenter of the pandemic.

Not long after Linette arrived at the event, she was approached by A.J. Burleson, a local leader in COVID-19 response efforts. Burleson was informing partygoers that they could get their vaccine on-site that day and asked Linette if she’d like to receive one. She declined.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

“Well, Dr. Rhoads will give them,” Burleson countered, referring to Kim Rhoads, a physician and associate professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), who has worked relentlessly to bring COVID-19 testing and vaccinations directly to Black people in the Bay Area. In the process, she’s earned a reputation among locals as a fierce advocate for the community and a trusted medical adviser.

Linette paused. “Dr. Rhoads?”

Burleson nodded.

“OK,” Linette said, her voice trailing off. “I’ll talk to Dr. Rhoads.”

Community takes care of community

Rhoads, who directs the Office of Community Engagement at the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, has a long history of leading community-oriented projects. Last year, she pivoted her office’s focus toward fighting COVID-19 in some of the hardest hit communities in California—particularly among Black populations, who were suffering the highest mortality rates nationally. Throughout the pandemic, she’s challenged established power structures and pursued innovative strategies to increase testing and vaccination in marginalized communities. Not only has her strategy appeared to work—thus potentially informing broader initiatives aimed at closing the health equity gap—but it also has helped transform the view of medicine in neighborhoods where doctors aren’t always trusted.

That transformation began by consistently showing up in the community, Rhoads says. Prior to the pandemic, she made sure UCSF’s cancer center had a constant presence at local events. Importantly, the center didn’t show up solely to enroll participants in research studies. The goal was simply to be a resource for the community, a tactic Rhoads has dubbed “year-round nontransactional engagement.”

Early in the pandemic, Rhoads saw that efforts to encourage COVID-19 testing weren’t reaching the Black community. So, she took matters into her own hands and launched her first COVID-19 pop-up testing site at Sunnydale’s June 2020 Family Day. The crowd was small, but a handful of people got tested. Her work was noticed.

Soon after, local community and health leaders approached Rhoads for help tracking down people who had been potentially exposed to the virus at a neighborhood party. Rhoads agreed and recruited Burleson. Together, relying on community knowledge and established local relationships, the team successfully contact-traced the partygoers.

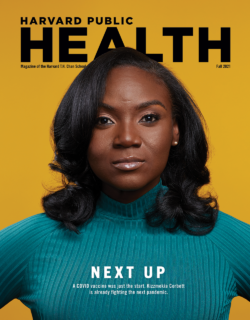

Transforming the view of medicine in neighborhoods where doctors aren’t always trusted starts by consistently showing up, Kim Rhoads says.

For Rhoads, it was proof that community members in historically underserved areas can leverage their resources to care for themselves—sometimes better than the regional health departments and medical institutions that come up short time and again. “That [insight] was a slap across my face,” she says.

From that point on, Rhoads, a self-proclaimed “troublemaker,” pushed hard against COVID-19 responses that left out community input. For example, when she learned that ZIP codes in Alameda County where COVID-19 spread the fastest were also home to the residents least likely to test, she voiced her concerns to local government officials about the ways in which the county’s mass-testing sites failed to serve the communities most in need. Eventually, the county changed tactics and concentrated efforts on hyperlocal testing in higher-risk neighborhoods.

Rhoads’ relentlessness is fed by her urgent desire to ensure that Black communities don’t get left out in the fight against coronavirus, says Jonathan Fuchs, the former head of testing strategy for COVID-19 in San Francisco and lead of the city’s neighborhood vaccine effort. The pair worked together to ensure broad availability of testing and vaccines to communities hardest hit by the pandemic, removing barriers such as proof of insurance, bringing testing and vaccine sites to accessible locations, and vetting vendors for any history of ethical lapses.

In August 2020, she similarly voiced her concerns over a UCSF mass-testing event aimed toward Black residents in Oakland. In her eyes, it was doomed to fail as the location wouldn’t serve Oakland’s interspersed Black neighborhoods. Moreover, she feared that branding it as a university campaign might dissuade residents who distrust medical institutions. Although she agreed to run the event, Rhoads breathed a sigh of relief when it ultimately had to be canceled due to inclement weather. It was like a sign. From here on out, she would do things her way.

Rhoads with (from left) team members Eva Pardo and Ghilamichael Andemeskel, and community volunteer A.J. Burleson.

Photo: Anastasiia Sapon for UCSF Magazine

Building a network, gaining trust

That meant building a COVID-19–focused health network from the ground up. Rhoads met with Black pastors and other community members and brought together dozens of organizations, including the Alameda County Public Health Department and UCSF. The endeavor crystallized into a grassroots group called Umoja Health, or “Unity” Health.

Under Umoja’s banner, Rhoads planned a series of mini testing pop-ups in locations where high concentrations of Black residents live and locals gather, such as parks, churches, and farmers markets—the first such events in San Francisco and Alameda County. A key part of the plan was that the events wouldn’t “look like medicine,” Rhoads says.

She ditched her white coat for an Umoja tee and leveraged community members and activists for her team like Burleson, documentarian Kevin Epps, and community health educator Ghila Andemeskel.

“We wanted to make sure our programs didn’t feel like UCSF, or that the public health department is inviting you to come get a test, because the natural response to that for many Black residents is, ‘What do they care about us?’” Rhoads says. “Whereas if your neighbors knock on your door, you’re like, ‘Oh, hey, it’s my neighbor. She cares about me, so I’m going to go get a test.’”

To boost participation, Epps and Burleson canvassed neighborhoods and discussed residents’ reservations before the pop-ups. Epps, who has his own misgivings about the medical establishment, was an empathetic listener. “I have my concerns about Tuskegee and what was done to Black men,” he says, referring to an infamous study on the progress of untreated syphilis by the U.S. Public Health Service. Black men in Alabama were enrolled in the study under the pretense that they would receive free medical care. They did not, and many died as a result. Despite feeling the weight of such a traumatizing legacy, Epps says, “Working with Dr. Rhoads gave me a sense of trust.”

After each pop-up, Rhoads and her team hosted public Zoom meetings to debrief the community at large, share data, and respond to any questions and suggestions.

By the fall, Umoja’s reputation grew, and so did the crowds. At least 65 percent of the testers were Black, a significantly higher percentage than at most testing programs, including some at trusted local Black clinics. More than half were first-time testers.

The success of Umoja’s testing pop-ups paved the way for vaccination campaigns. When Umoja launched its first vaccine clinics, people lined up around the block.

“It’s street certified,” Burleson says with a grin.

Rhoads administered COVID-19 vaccines and answered questions at a block party in June.

Photo: Annika Hom

Finding a way or making one

Rhoads didn’t always want to be a doctor. She thrived in science but chose linguistics for undergraduate school at University of California–Berkeley. Nevertheless, she took the prerequisites for medical school and remained open-minded.

After graduation, Rhoads landed a job studying HIV variants in Washington, D.C., at the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine. She frequently visited her family in Virginia, who revealed their often-negative experiences with the health care system. Her aunt lamented a lack of clinics where “you walk in and people know you.”

While working at Jackson Foundation, Rhoads met a man with AIDS at a party and the conversation left her feeling conflicted about research science. While her daily work in the lab was aimed at beating AIDS, at this moment, it wasn’t helping this man—or any other HIV-positive person. So, she changed course and attended medical school.

Hoping to make an impact through both direct patient care and public health, Rhoads chose the UC Berkeley-UCSF Joint Medical Program. During her first year in 1993, a guest speaker from Oakland’s Third World Organizing Center inspired her to enroll in its community organizing course, where she learned to “sit in people’s front yards and make demands.” At the course’s graduation, students received shirts that said: “We will either find a way or make one.”

During her second year at medical school, Rhoads’ aunt died of breast cancer. Her passing fueled Rhoads to focus her thesis on racial disparities in breast cancer treatment. Today, whenever Rhoads presents about this topic—particularly on the poor quality of care in minority-serving hospitals—her first slide features her aunt.

Rhoads kept pushing herself along a path to promote health equity as she forged ahead in her career and personal life. She joined organizations like the Bay Area Black Women’s Health Project and worked on educating the community about breast cancer as a legislative intern for U.S. Representative Barbara Lee.

Later, as a resident specializing in surgery, she had her first child, a daughter. On that day, Rhoads recalls, she finished her rounds at 12:30, arrived at the children’s hospital at 1:00, and gave birth in 20 minutes. “It’s kind of legendary,” she jokes. Soon after, she resumed work, not wanting pregnancy to be an obstacle for any future residents. In her last year of surgery residency, she became pregnant with her second child, a son.

At the height of all this activity, Rhoads already had her next step in mind—Harvard’s California Endowment Scholars in Health Policy, a highly selective program focused on policy and health inequities. Rhoads says, “I was like, ‘This program was literally created for me!’”

Accepted in 2005, she moved to Boston with her husband and children to study for an MPH degree from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Her program was one of several fellowships founded and directed by Joan Reede, professor in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the Harvard Chan School and Dean for Diversity and Community Partnership at Harvard Medical School. Alumni participants in these programs are known as Reede Scholars.

Even as a student, Rhoads had mastered treating the community as an equal partner in her work, says her Harvard Chan School mentor Joan Reede. “When you bring your authentic self to your work, people can tell.”

Rhoads was inspired by Reede’s guiding philosophy of community health work: “Do with, not to or for.” She took leadership classes, too, and learned to leverage other people’s perceptions of her—or the “role” she was expected to play as a Black person, doctor, and woman.

Even as a student, Rhoads had mastered treating the community as an equal partner in her work, Reede says. Her student’s success with Umoja years later came as no surprise, Reede says. “When you bring your authentic self to your work, people can tell.”

Personal approach

That authenticity shone at Family Day 2021, when Rhoads spoke to Linette, the reluctant vaccine recipient. Linette, 50, was among few San Franciscans—less than 30 percent—who weren’t fully inoculated by June.

Linette explained her fear that the country’s medical system was apathetic to Black people. Her grandmother was from Alabama and knew people affected by the Tuskegee experiment. Linette braced for patronization, but Rhoads validated her concerns and fielded her questions. Her respect for personal choice and care with words—Rhoads condemns rhetoric around vaccine hesitancy, which she sees as racialized code for “uninformed and poor”—appeared to allow Linette and others to finally feel heard.

So, Linette got a shot that day. This puts her among the 98 percent of other Umoja pop-up participants who had received their second shot as of June, outpacing second vaccination rates at other local sites.

While other testing and vaccination campaigns faded by the start of the summer, Umoja geared up to continue its work. Rhoads came to Family Day in a new van she bought for the organization that will be used to target hyperlocal areas with in-home vaccinations. “There’s still a ton of work to do, but Umoja Health is in a good position to do it,” Rhoads says. As it has been throughout the pandemic, her goal is to be “highly visible, recognized as a resource, and sought after for information, support, and service.”

When the COVID-19 crisis finally fades, Rhoads hopes to pivot the Umoja model to address cancer in the Black community and the systemic factors that foster health inequities. She also wants to train Umoja’s members to become community health leaders.

In between vaccinations that June day in Sunnydale, Rhoads took some time to kick back and have fun with her team and the community they’ve become part of. When a reporter asked for a photo of the van, she slid into the front seat while her colleagues, including Burleson, Epps, and Andemeskel, leaned on the side of the brand-new ride, teasing each other before posing. Burleson grinned triumphantly. “It’s like an album cover.”

Top photo: Anastasiia Sapon for UCSF Magazine