People

Cultivating food justice, one garden at a time

The Regional Environmental Council (REC) has been active for 50 years in Worcester, Mass., a city of 200,000 with a large immigrant population and a poverty rate of nearly 20%.

The nonprofit supports a network of 67 community gardens and employs several dozen teens to work on two urban organic farms. Last year, the teens grew more than 4,500 pounds of food, which REC loaded into vans to serve at mobile farmer’s markets, bringing fresh and affordable produce to underserved neighborhoods across Worcester.

REC executive director Steve Fischer started as a volunteer. He spoke with Harvard Public Health about the importance of food justice in closing health equity gaps. This Q&A has been lightly edited for clarity.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Q: How did you come to see farming as a component of social justice?

A: REC started as an all-volunteer effort to work on what we think of as traditional environmental issues: open space, clean water, clean air. Over time, we started thinking: What about healthy food? It seems to be an important resource as well. In 1995, we established five community gardens in Worcester. They’ve grown to such a degree that over the last decade, food justice has been the primary focus of our organization.

Q: How would you define food justice?

A: There’s a systematic discrepancy in the way that we all get access to the good things in the world, and the way we’re exposed to bad things. And it’s stratified by class, race, and gender—access is stratified in all the ways that you might imagine.

And what’s true for access to good jobs, housing, clean air, and clean water is true for food as well. Depending on where you live and who you are, you might have a harder time getting access to healthy food, or you might have an overabundance of fast food and highly processed foods in your neighborhood.

Our organization tries to help people in our community work together to address this issue. And we do that by looking at what we call the “two P’s” and “two E’s” of healthy food access: price and proximity and education and empowerment.

Q: Is your work strictly about delivering healthy food to neighborhoods that need it?

A: We are very interested in helping to create a community that has access to healthier food, more local food, and culturally appropriate, affordable food. That’s a big part of what drives us.

But in other ways, food is just part of our work. We have run urban farming programs for youth for 20 years. The youth come to understand the food system better and they may make an impact in the way their families eat. But the primary goal of these programs is to grow healthy human beings. The youth who work with us discover an ability to make an impact in their communities. And that can shift their mindsets around what’s possible for them in their lives.

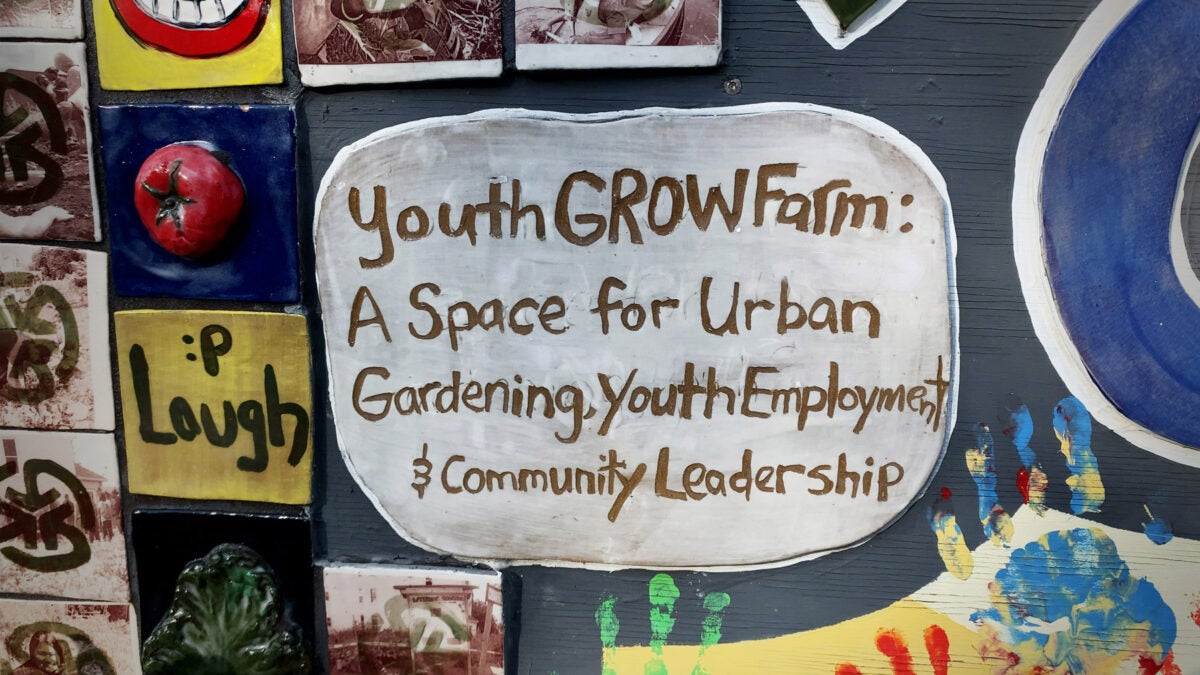

YouthGROW employees are teenagers, 14 to 18 years old, who learn leadership skills and receive job training while working two urban organic farms.

YouthGROW is one of three programs that REC offers.

Q: Do the teens who work with you talk about these issues in terms of structural racism?

A: These teenagers come to the program with an understanding that in the neighborhoods where they live, there are inherent challenges that make it more difficult for their families to access healthy foods, and they know that’s not necessarily true for all neighborhoods in the city.

They might not have heard the term ‘food justice,’ so we’ll pull that out and parse it. But they know what food justice is, and they know why there are disparities in our society.

Q: How do you measure your impact as an organization?

A: Robust evaluation is often a challenge for grassroots organizations like ours. We haven’t been able to fund a longitudinal study which would show the long-term health impact of our program.

But we do run focus groups and surveys on an annual basis. And the folks who participate tell us, yes, this is having a positive effect on my family’s ability to eat healthy food. They say they know they’re healthier because they now shop at our farmer’s markets, or because they have a plot in a community garden. They also often say they have a youth in the program who has talked to them about healthy cooking at home. We know that we are absolutely having an impact on the folks we serve.

Q: How do you see the food justice movement evolving?

A: Over the last 10 or 15 years, there’s been an accelerated understanding about the importance of the way food is grown, eaten, and the way we treat folks who are responsible for growing our food. There’s attention to how methods of production and patterns of consumption impact the broader environment.

There is a stronger realization of these factors now than at any other time in my lifetime. That’s what gives me optimism. I see more and more really smart, really good-hearted people wanting to make a change in the sphere of food justice. And that’s a great reason to be optimistic.