Feature

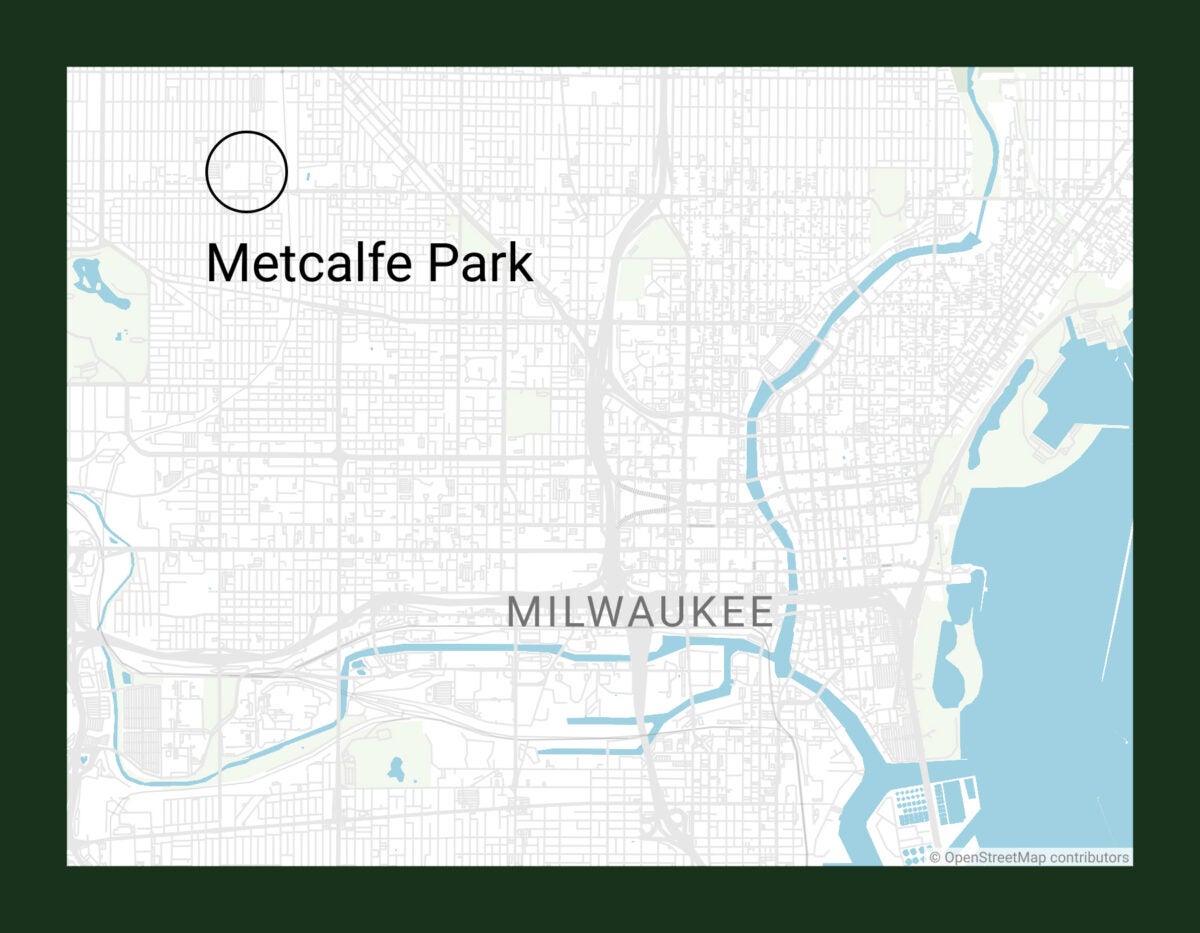

Metcalfe Park: Inside structural racism’s invisible net

In Milwaukee’s Metcalfe Park, corner stores are the main places for residents to buy food. There is one grocery store, but much of the neighborhood is considered a food desert.

Danell Cross doesn’t mince words when discussing her health issues. “I have an enlarged heart, high blood pressure, hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis,” she says. “My sinuses are shot, my glands are swollen … and I am morbidly obese.”

Her doctor has advised her to lose weight and quit smoking. She knows she should.

So Cross, 57, is putting her formidable energy toward social change. She’s the executive director of Metcalfe Park Community Bridges, a community organization fighting to overcome the painful legacy of structural racism—a legacy that has made her neighborhood an exceedingly tough place to be healthy.

But in many ways, she feels the deck is stacked against her: The grocery store in her struggling Milwaukee neighborhood isn’t clean and doesn’t have the low-sodium and other specialty foods ideal for her diet that she sees in suburban stores. She grows what tomatoes she can in raised beds because she’s concerned about toxins in the soil. And she is burdened by stress and worry, not least because her adult children face similarly daunting health challenges.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Metcalfe Park, in northwest Milwaukee, is a community of about 9,000, more than 80 percent of whom are Black. Median annual income is under $18,000, and 46 percent of residents live below the poverty line, according to a 2020 report from the community organization. It’s one of the three most dangerous neighborhoods in Milwaukee, with FBI data on violent crime putting it 1,100 percent above the national average.

Residents talk about being stifled by an “invisible net” that blocks advancement and makes it nearly impossible to maintain good health. Environmental pollution is woven into that net. So are poor public schools and lack of economic opportunity.

The community report quotes one resident describing the net this way: “You can’t see it. Our kids can’t see it, but no matter how hard they try, no matter how well they play the rules, when they try to advance, they get stuck in the net. It traps us in.”

Cross feels that oppression acutely. And she knows it has harmed her health and the health of her family and her neighbors. “We’re fighting a million battles at the same time,” she says. “We have built cross-community collaborations on environmental justice, fighting against lead that’s still in the paint in the houses, the toxic ground, concrete dust, rodents.”

And still they’re losing ground.

It’s not just Metcalfe Park, either: Milwaukee has the worst Black poverty rate of the 50 largest metropolitan areas in the U.S., according to a 2020 study from the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. One in three Black city residents lives in poverty, compared to 7 percent of white city residents. The Black home ownership rate is the second worst in the country, after Minneapolis. Milwaukee is the nation’s most segregated city; 72 percent of Black students attend extremely segregated schools.

These harsh realities translate into dismal health outcomes. According to a 2020 report from the county coroner’s office, the life expectancy for white Milwaukeeans is nearly 75 years. For Black residents, it’s 62.

Accessing healthy food is among the most pressing of Cross’s concerns. There are many corner stores in Metcalfe Park and the surrounding area—which means there are plenty of places to buy high-salt, high-fat snacks. There is only one grocery store, a Pick ’n Save.

Melody McCurtis, Cross’s daughter and deputy director of Metcalfe Park Community Bridges, says the neighborhood Pick ’n Save rarely has the same offerings as those in more affluent areas, prompting her to head to the suburbs for fresh meat, fish, and produce.

Cross, too, said she drives at least 20 minutes (the bus would take 90 minutes) to reach the closest “decent” supermarket. “The best things are always in the suburbs. I went to the Pick ’n Save in a suburb and thought I was in heaven,” she says.

Before she started working, Cross was one of many Metcalfe Park residents who used food stamps for groceries. She often needed to pay someone with a car to transport her and her purchases, which meant she tried to limit shopping to once a month—a stressful and often demoralizing trip. “When you’re on food stamps, you have to buy in bulk to last a whole month,” she says. “That’s how I shopped for years until I got this job and started making some money. When you go into the grocery store, and you got three shopping carts, everybody is mad at you. People who don’t get food stamps are mad at you, and the cashier is mad because you have to buy so much.”

Buying in bulk makes little sense for fresh fruits and vegetables. “You cannot save fresh foods,” Cross says. “You’re buying canned foods and all the white rice you can because it stretches a meal. Apples and oranges would last just a day in my house. The rest of the month it’s canned peaches, canned pineapples, everything that is in a can because they last.”

When such items run low and rides to the grocery store aren’t available, residents are at the mercy of the corner stores, which have limited supply and often much higher prices.

Jared Olson, who holds a doctorate in public health and community from the Medical College of Wisconsin, has been working with Cross and Metcalfe Park Community Bridges for five years. He now serves on the organization’s board of directors. Olson calls Metcalfe Park a food desert, an urban area where it is difficult to buy good-quality fresh food. “There is an association between neighborhoods of color, Black neighborhoods, and food deserts,” he says. “Layer onto that lower levels of car ownership in these communities as well and you can find yourself in a tough situation.”

The lack of access to healthy foods takes a toll, Cross says: “I have six kids and almost all of them are morbidly obese. All of my neighbors are overweight. Not only overweight but smoking. Every store around here sells candy, nachos, cheese fries, and cigarettes.”

Cross said it wasn’t until she took her current job, which led her to travel far outside her neighborhood, that she recognized how much her environment affected her diet, and by extension, her health. “When I go to D.C. for meetings, I’m not drinking energy drinks,” she says. “I drink cold water. But when I get back home, I can’t find anything but energy drinks. There’s nothing that’s not full of sugar in my neighborhood. If I hadn’t gotten involved in this kind of work, I would never have noticed.”

The sad reality, she observes, is that many of those who live in areas like Metcalfe Park lack opportunities to travel outside their neighborhood. “We don’t even know how other people live and what they have access to,” she says.

Living within the confines of Metcalfe Park also means constant exposure to structural violence and loss. “I’ve lost almost 100 friends and I’m only 29,” McCurtis says. “Our young people aren’t able to even grieve because it’s so constant. White people are able to live in peace and thrive in their lives. So many of us can’t. We are not valued.”

Cross experienced violence firsthand after she reported a suspected drug house to the authorities. “Somebody threw a Molotov cocktail bomb through my window. It burned the house up. Me and my baby were in there asleep,” she says. She moved just outside the borders of Metcalfe Park. Yet she remains closely tied to her former neighborhood—and determined to lead its revitalization. As she puts it: “I have always been a shit starter.”

Cross was volunteering at Head Start when it got a grant from the federal government’s Building Neighborhood Capacity Program. It wanted to hire someone who knew the community and encouraged her to apply. Her volunteer work showed an ability to bring people together, says Linda Bowen, who runs the Institute for Community Peace in Washington, D.C. and consulted on the project.

“Danell was able to rally her community to deal with the murder of a young Black girl who was killed when someone was in a neighborhood park and started shooting,” Bowen says. “Funders saw how Danell was able to get the community together.”

The more Cross worked on community revitalization, the more she recognized how widespread health issues were in Metcalfe Park. Everyone, it seemed, was dealing with similar challenges, the kinds brought on by living in older residential stock near industrial facilities. “Two of my kids have lead poisoning,” she says. “Everybody is smoking and eating garbage, living with fumes and toxicity.” Cross says asthma in the neighborhood is “off the Richter scale.”

“I have asthma pretty bad, and I have diabetes,” says Patrice Gransberry, 61, who lives in a senior living apartment building in Metcalfe Park. Neighborhood residents suffer higher rates of asthma and diabetes, as well as high blood pressure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, than the city as a whole. To Gransberry, the reasons are clear: “There’s dust coming up from vents, garbage all around the building with maggots, grass that they don’t halfway cut. I’ve been here five years and my asthma has been worse the last two years than before. And my two grandkids have asthma as well.”

Widespread asthma is no coincidence, Olson says: “Indoor air quality is a real challenge—you hear folks talking about rodents, mold, and extremely wet conditions” in their homes. He hears similar stories across Milwaukee—especially in parts of the city with older housing stock “that’s been least maintained, that has the most tax liens, the highest number of code violations,” and are majority Black, Olson says. “That uneven distribution is something you can trace back to structural racism.”

Metcalfe Park is also among the Milwaukee neighborhoods most vulnerable to air pollution and dangerous temperatures during “extreme heat events” that are expected to become more common due to climate change, according to the nonprofit group Groundwork Milwaukee. It’s among the most vulnerable to extreme flooding, too.

Metcalfe Park’s blueprint for a better future, the Community-Led Investment Plan, starts with a look at the past. For decades, this was a vibrant neighborhood, with working-class families from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. Adults walked to factory jobs that paid living wages. There was a park with basketball nets and a clubhouse for community events. But a slow decline began in the 1960s, when the city destroyed hundreds of homes and stores to clear space for a freeway that was never built. That process “displaced social networks and weakened local institutions,” the report recounts. The recession in the 1980s led factories to shut down or cut workers. Unemployment and crime rose. The housing crash of 2008 set the neighborhood back still further, as abandoned and foreclosed properties became magnets for crime and vandalism.

The revitalization process that began in 2012 included intensive training for residents on how to work with city officials, outside funders, and organizational partners. Over time, residents developed a strategic plan for prioritizing safety, creating green space, and building more opportunities for community gatherings and recreation. The group worked with city agencies to bring public officials to walk the neighborhoods, knocking on doors and answering questions.

The activists also launched a focused initiative to improve health in the neighborhood. A partnership with the Medical College of Wisconsin led to smoking cessation workshops, classes in yoga and mindfulness, and wellness fairs. And the group created community gardens with raised planter beds. “We can’t have [home] gardens because the ground is so poisoned with toxic chemicals,” Cross says. For the neighborhood gardens, “we have to use planters and build them three feet up so the roots don’t touch the ground,” she says. “And we have to bring in our own dirt. The whole area is toxic and we don’t want anything touching the ground.”

(City and county officials did not respond to numerous requests for comment on environmental pollution in Metcalfe Park.)

It’s been a great deal of work, and a mountain of tasks remain. McCurtis says the payoff comes from responding to the community. She, her mother, and the neighbors they work with take enormous pride in working to improve their community. As it turns out, working to combat the legacy of structural racism has a health benefit, too. Everyone smiles more, she said—and “their blood pressure goes down.”

Top image: In Milwaukee’s Metcalfe Park, corner stores are the main places for residents to buy food. There is one grocery store, but much of the neighborhood is considered a food desert.