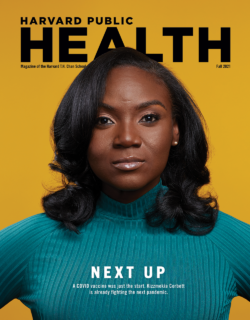

Happy (left) and her sister Nastrinia, Congolese immigrants in Clarkston, Georgia, discussing their experience with health care in the United States. Vngle

Feature

For many immigrants, U.S. health care is a maze without a map

Somali Plaza in Clarkston, Georgia is the heart of its East African community, a place where Somali, Arabic, and other languages fill the air. People browse shelves stocked with traditional foods, prayer mats, and clothing, part of the rich cultural tapestry in what is often called the “Ellis Island of the South.” Immigrants, many once refugees, are from over 150 countries and speak more than 60 languages. Half of its roughly 14,000 residents were born outside of the United States, but they share one common struggle: access to health care.

Happy, a Congolese volunteer health care interpreter who requested to share only her first name, helps guide others through a health care system that often feels like a labyrinth. Her experience with the system does not spare her own family from its barriers. [Editor’s note: Harvard Public Health is not citing the full name of Happy and several other interviewees to protect them and their families, due to concern about anti-immigrant sentiment and also cultural norms within some immigrant communities.]

Happy’s younger sister, Nastrinia, has suffered for months from persistent hand tremors and frequent vomiting. Their parents, desperate for answers, have taken her to multiple clinics, only to leave each time with uncertainty. One doctor prescribed nausea medication. Another suggested it might be stress. But no one has given them a clear diagnosis. The language barrier makes every visit more frustrating, given that her parents struggle to communicate their daughter’s symptoms in English. “It’s scary to watch,” Happy says. “And it takes a toll on our family.”

She sees similar struggles play out when she volunteers, watching mothers try to explain their children’s symptoms in broken English, only to be misunderstood repeatedly throughout their appointments. She sees elderly refugees struggle to fill out complex paperwork, their frustration mounting. And she sees the fear in their eyes, the fear that the system will fail them as their hopes for a better life are met with the same hurdles they’ve seen so many others face.

Across Clarkston, which lies about 10 miles northeast of downtown Atlanta, residents face systemic obstacles, language barriers, financial constraints, and a U.S. health care system that often lacks cultural competence. A former medical scribe who requested anonymity to protect his professional and academic standing recalls assisting an Afghan father seeking specialized care for his child. The process required a four-way exchange between the scribe, a Pashto-speaking interpreter, a nurse practitioner, and the family. Despite their best efforts, translation errors led to incorrect appointment details, forcing the family to restart the process. Every mistranslation costs two things many people in Clarkston lack: time and money.

Humaira Shirzai and her husband, both originally from Afghanistan, often skip doctor visits to avoid the upfront appointment fees, and forgo necessary medications due to costs. They don’t have Medicaid, but she says people who do still face barriers—including limited provider acceptance, upfront costs for care, and delayed reimbursements—which can leave them in financial limbo and delay necessary care.

Clarkston’s leaders recognize the urgency of these issues. Mayor Beverly Burks previously worked as a community engagement director at Fulton-Dekalb Hospital Authority, and City Councilwoman Sharifa Adde, who came to the U.S. as a refugee, have spent years advocating for refugee and immigrant families. Both stress that while progress has been made in recent years, the health care system remains difficult to navigate for many. Omar Shekhey, founder of the Somali American Community Center, works to address these barriers by building trust with residents about their health care needs. “Trust means knowing who you can open up to,” he says. “Without it, people hesitate to seek care until it’s too late.”

As Burks, Adde, and Shekhey make their way through Somali Plaza, stopping to speak with residents, it’s clear that immigrants and refugees have developed a rapport with local leaders. That’s not unusual in the U.S. where despite deep distrust of the federal government, about two-thirds of people say they trust local government. Health-related institutions are far more trusted, with 82 percent saying they trust hospitals and 79 percent public health departments. That’s less true for many refugees and recent immigrants, who face a challenge they never encountered in their home countries: barriers to accessing proper health care. Those barriers are even more pronounced in Georgia, where health care access ranks among the worst in the nation.

Language barriers, cultural insensitivity, and systemic obstacles such as lack of insurance and transportation all prevent residents from accessing health care, says Abdi Yusuf, who moved to Clarkston in 1993. Yusuf, originally from Somalia, works as a health care underwriter and sees these challenges play out daily. He says “Many refugees don’t know the language and don’t get the best jobs, which makes access to health care harder.”

Many of the refugees who arrive in the U.S. hold advanced professional jobs in their home countries, but here find themselves relegated to low-wage jobs due to licensing and accreditation barriers, as well as limited English proficiency. Where interpretation services exist, they are often insufficient. The Georgia Department of Public Health’s Refugee Health Program provides interpreters only in Somali, Arabic, Dari, and Pashto. In Clarkston, with its 60+ languages, many residents must rely on other means to navigate the system. Too often these challenges mean they delay or completely avoid medical care.

Some 30 percent of respondents to a 2023 Clarkston Needs assessment conducted by Georgia State University’s Prevention Research Center had not visited a doctor for a regular check-up in the past year, and an equal number delayed medical care due to cost concerns. The rate is almost double Georgia’s overall 15.5 percent of residents who skip medical care due to costs, which is the second-highest percentage in the nation.

In Clarkston, several community-led health care initiatives are working to bridge gaps and provide access to care for those facing financial hardship.

Grace Village Medical Clinic, a free clinic, operates just five times a month, yet in each five-hour clinic session, it serves about 40-50 patients, many suffering from chronic illnesses like diabetes and hypertension. Despite its limited hours, the clinic provides continuity of care to over 2,000 patients annually by leveraging a volunteer staff of physicians, nurse practitioners, and medical students. At its core, Grace strives to serve as a family physician for residents with limited health care options.

Mosaic Health Center, formerly Clarkston Community Health Center, takes a similar approach, helping to reduce financial barriers to health care while reinforcing the importance of trust in medical services. “If equitable solutions can be found in the most diverse square mile, similar models can succeed anywhere in America,” says Jeremy Cole, its executive director. Since 2013, Mosaic has provided free or subsidized care to thousands of uninsured and underinsured patients, with a focus on preventative medicine, chronic disease management, and health education. Its motto is “People care over profit share,” and the clinic aims to give residents facing financial hardship access to care.

While these clinics provide crucial support, they don’t meet demand and still struggle with systemic barriers, especially translation. Though both organizations lean on local interpreters and language lines to serve their global patient profiles, gaps still occur. “You never know what language we will serve any given day,” says Michael Sorrells, Grace Village’s CEO.

Grace Village and Mosaic are open to any Clarkston resident who needs their services; Ethnē Health, a primary care clinic, moved into the city in 2017 and in 2018 opened a community clinic specifically to serve its international population. Ethnē tries to address barriers faced by refugees and immigrants, by hiring multilingual staff from the community. Like Grace and Mosaic, it utilizes a language access line for real-time translation to support patient needs. It also works to address the connection between health and social conditions, prioritizing immediate needs such as food insecurity, housing, and mental health before shifting to long-term wellness.

“Building trust over time is essential,” says Robert Contino, Ethnē’s CEO. Ethnē has developed partnerships with organizations like MAP International to provide free prescription medications. It also offers free Uber rides for patients without reliable transit. And it coordinates with local hospitals and community organizations to ensure that Clarkston residents receive continuous and culturally competent care. Many residents told us that Ethnē is a trusted option for their health care and praise it for working to serve the community’s evolving needs. Ethnē serves patients with insurance as well as those who are uninsured and underinsured, which has given it flexibility to coordinate available services and to expand its services, as it did in 2023, when it started the first dental clinic in Clarkston for immigrants.

“The need for quality dental care is tremendous,” says Contino, noting that many Clarkston residents have never seen a dentist before arriving in the U.S. But dental services require specialized infrastructure, sterilized equipment, dental chairs, and power tools, all of which are costly to establish and maintain. “Dentistry is harder to provide than primary care because of the infrastructure required,” says Nate Benard of the Christian Medical and Dental Association. “But without access to dental care, small issues quickly escalate into severe problems.” In Clarkston, that lack of routine dental care has led to severe infections, tooth loss, and chronic pain, creating a citywide public health concern.

Sheela Poya, a former refugee from Afghanistan who now works as a case manager at an Afghan refugee support organization, recalls how her family endured severe dental pain for years with no access to affordable treatment. “A $4,000 to $5,000 dental procedure is impossible for someone making $2,500 a month,” she explains through a translator. She says her family opted to use painkillers to deal with dental issues, rather than seek proper care. She wants policymakers to expand Medicaid coverage and increase cost relief for Afghan families and other low-income residents.

Poya’s story is far from unique. A dentistry needs analysis on Clarkston conducted by Georgia State University’s Prevention Research Center found:

- Most community residents do not visit the dentist for preventive care.

- While residents can seek treatment for urgent dental issues, cost and lack of insurance severely limit available services.

- Children receive regular cleanings and checkups, but many parents only visit the dentist when experiencing severe pain or complications.

- There are no in-language educational materials to help residents understand their dental health options.

A college student named Najwa from Sudan, who wished to not be fully identified to protect her family’s privacy, shared how her younger brother’s dental care became a saga of missed opportunities and misinformation. In particular, her mother accidentally switched her brother’s Medicaid plan due to a translation error, causing the family to have a six-month gap in coverage. During this period, his untreated cavities worsened, yet cultural misconceptions about dentistry from the community, such as the belief that it is “just a business” seeking to get you to come back, delayed them from seeking proper care. Instead, they were advised to rely on herbal remedies.

Many of the refugees in Clarkston escaped conflict zones, but they still hold the trauma of war, displacement, and loss. “A lot of people have seen horrible things … walking through forests, seeing people dead. Many are suffering, especially the kids,” says Yusuf, the Somalian health care underwriter. In the U.S., they have to navigate an unfamiliar health care system, which compounds their stress by giving them paperwork they can’t translate and leaving them uncertain about where to turn for help. These factors, financial insecurity, and cultural stigmas make seeking mental health care a challenge.

Some community organizations have worked to become trusted pillars, providing mental health support tailored to the cultural and linguistic needs of Clarkston’s residents.

The Amani Women Center has created safe spaces where women can heal, seek support, and rebuild their sense of agency. It has adopted “sister circles” that allow refugee women to discuss trauma, domestic violence, and health concerns in a culturally sensitive and supportive space. Amani also offers a community ambassador program, which pairs refugees with mentors from their own cultural backgrounds to help them navigate the health care system. “Diversity calls for solutions that are not templates,” says Doris Mukangu, Amani’s founder and executive director. “You must be creative to connect with hard-to-reach communities.”

Amani’s focus on culturally competent care extends to addressing religious nuances, literacy challenges, and social isolation. Previously, this organization has also collaborated with agencies like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to tackle sensitive cultural issues such as female genital mutilation (FGM), which many refugee women in Clarkston experienced before arriving in the U.S. These interventions provide critical education and support while fostering trust in medical institutions that many refugees instinctively avoid.

One of Amani’s most impactful initiatives is its sewing program, which began in 2006 with just two women and has since grown to serve over 100 participants from Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia, Burma, Afghanistan, and beyond. The program combines economic empowerment with mental health support, giving women skills to achieve financial independence while fostering a sense of belonging. Mukangu says 65 percent of program alumni have started home-based businesses, 70 percent earn a living wage, and 95 percent have opened savings accounts. Clarkston Councilwoman Adde, a graduate of the program, says, “For many women, this was the first time they had an opportunity to achieve self-sufficiency.”

Shekhey, founder of the Somali American Community Center, has spent over 25 years working with refugees, helping them navigate not only the complexities of the health care system but also the deeply ingrained cultural stigmas that prevent many from speaking openly about their struggles. Language barriers compound cultural taboos, since “[feeling unable] to communicate itself is a health issue,” Shekhey says. Mental health is a particular issue, since In the Somali community, terms like mental illness and suicide are rarely spoken aloud. Instead, suffering is often internalized, seen as a private burden rather than something to be treated. Death from any cause is not discussed. “People die, and their families don’t want their friends to know why,” says Shekhey. “They don’t want to be associated with it. It feels like a curse.”

Twice a week, Shekhey conducts informal mental health check-ins for those who cannot afford care or who are afraid to acknowledge the symptoms of a mental health condition. Using post-trauma questions as a guide, he created his own approach to help people open up about their struggles, ranging from daily life challenges to financial stress. He says he sees people suffering quietly, enduring chronic pain and sleepless nights, and others who are slipping into the substance abuse that afflicts the U.S. He listens to families hesitant to even say the word cancer aloud, fearing that naming it might make it real. And he works to connect them with the right support and advocate for their needs.

“Medication alone isn’t enough,” he says. “It’s key to give people your time.” Shekhey says he often spends two to three hours with a single community member, then follows up for weeks to try to ensure issues get addressed. In this way, the center serves as a place where people can discuss what they might not share in a doctor’s office. It’s also a space for correcting misinformation, a role that became critical during the COVID-19 pandemic when false rumors spread through the community, such as the fear that women who took the vaccine would never be able to have children.

Shekhey believes a community’s struggles are shared burdens. “If your neighbor is suffering, you’re suffering too. That’s our culture, that’s how you feel,” he says. It’s why he left a career in the U.S. in mechanical engineering to become a humanitarian. It’s why he believes that traditional surveys and evaluations often fail to capture the reality of immigrant experiences, because without truly knowing the community, the right questions aren’t even being asked.

Clarkston’s leaders recognize that addressing the city’s health care challenges requires more than just medical services, it demands trust, cultural understanding, and a commitment to long-term solutions. Community health workers play a vital role in this effort. Mobilized by organizations like Amani, the Refugee Women’s Network, and Ethnē Health, these workers help residents navigate complex systems, ensuring they receive timely and appropriate care. “Caseworkers are the bridge between residents and resources. They’re essential in breaking down barriers,” says Burks, the city’s mayor.

Burks acknowledges the scale of the challenge. Resources remain limited, and demand often outpaces available support. Achieving true health care equity, she notes, requires long-term investment from all levels of government and the ongoing involvement of community stakeholders.

Clarkston’s approach has been shaped by the belief that the most effective health care solutions come from those who truly understand the community. This philosophy led to higher vaccination rates during the Covid pandemic than in many similar populations, driven through partnerships with organizations like the Amani Women Center and multilingual outreach to address fears and misinformation. The Clarkston Health Equity Coalition (CHEC), created to boost Covid vaccine uptake, has evolved into a citywide network that brings together elected officials, medical professionals, university researchers, and grassroots leaders to tackle systemic health care disparities.

But Clarkston’s commitment to community-driven health care looks likely to face significant challenges due to shifts in federal policy. Proposed Medicaid cuts and uncertain funding for the community-focused Health Center Program could jeopardize care for vulnerable populations, warns Ethnē Health’s Contino, despite these clinics’ proven role in reducing health care costs.

Georgia is one of 10 states that did not expand Medicaid, and Burks fears that any cuts at the federal level will force more low-income and immigrant residents to rely on already overburdened clinics and emergency rooms.

Not everyone sees storms ahead. Grace Village’s Sorrells says, “Our approach to serving Clarkston and the surrounding communities will not change based on what we know today.” In fact, it expects to expand, adding more education and job training services.

But the times are uncertain, and Contino says he sees widespread anxiety among Ethnē’s staff and patients. Most of those patients are here legally via the highly vetted refugee resettlement process. “Even though nearly all have legal status, there is still deep concern about potential targeting from ICE officials,” he says.

If the federal government renounces prior commitments, these leaders say they remain committed to providing and expanding access to culturally competent care across this unique, vibrant community.

Editor’s note: Vngle is a grassroots news and intelligence agency dedicated to amplifying the voices of underrepresented communities. It collaborates with and offers journalism training to members of communities it reports on. Vngle spent nearly a year working with residents of Clarkston, Georgia, for this piece. Vngle’s reporting process is backed by a system of provenance records, ensuring the authenticity and traceability of the stories shared, even with anonymous contributions. This project was initially supported by the Starling Lab for Data Integrity, co-founded by Stanford University and the University of Southern California.