Feature

Voting is good for your health. These doctors want to help.

On a cold winter night more than five years ago, a woman brought her infant and toddler to Boston Children’s Hospital’s ER because they were shivering so hard that she worried they might die in their sleep. She’d recently fled an abusive partner in Philadelphia and moved her kids to Massachusetts to stay with her aunt. But her aunt kicked them out, and they’d been living in her minivan. To save her children from the dangerously low temperatures, she drove to the hospital. She didn’t know where else to go.

The doctor assigned to her that night was Alister Martin, who still remembers this encounter vividly. He wanted to help the woman and her kids find a place where they could stay—all three of them, so they could avoid the stress of a separation. A hospital social worker initially told Martin that the family would almost certainly get split up—the mother would be sent to an adult shelter, and the children to a shelter for kids—unless they could prove that the family were Massachusetts residents. Residency would qualify them for emergency family housing, thanks to the state’s “right to shelter” law.

And thanks to a 1993 law, registering the woman to vote would make her a resident—that very night.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

That law, often called the “motor voter law,” requires states to provide voter registration at the DMV. It also allows nonprofit health centers and facilities that treat Medicaid or Medicare patients to register people to vote.

Martin was thrilled to find a way to keep this family together—and he realized registering patients to vote could address a more systemic problem. “This experience showed me that health care systems could directly contribute to increasing voter registration and thus influence policies affecting health access and equity,” he says. Martin was keenly interested in policy and the more far-reaching changes policymakers could enact to help his patients; he had recently returned to medicine after getting his master’s in public policy from Harvard’s Kennedy School and serving as a health care policy aide to Vermont Governor Peter Shumlin. Before that icy night in the ER, Martin says, “I had never connected the dots between my work as a health care provider and my efforts in public policy—two roles I had always seen as distinct, as separate.”

Alister Martin, an emergency doctor, and Jaden Yoo, a physician's assistant, walk through the emergency department at Massachusetts General Hospital during a recent shift.

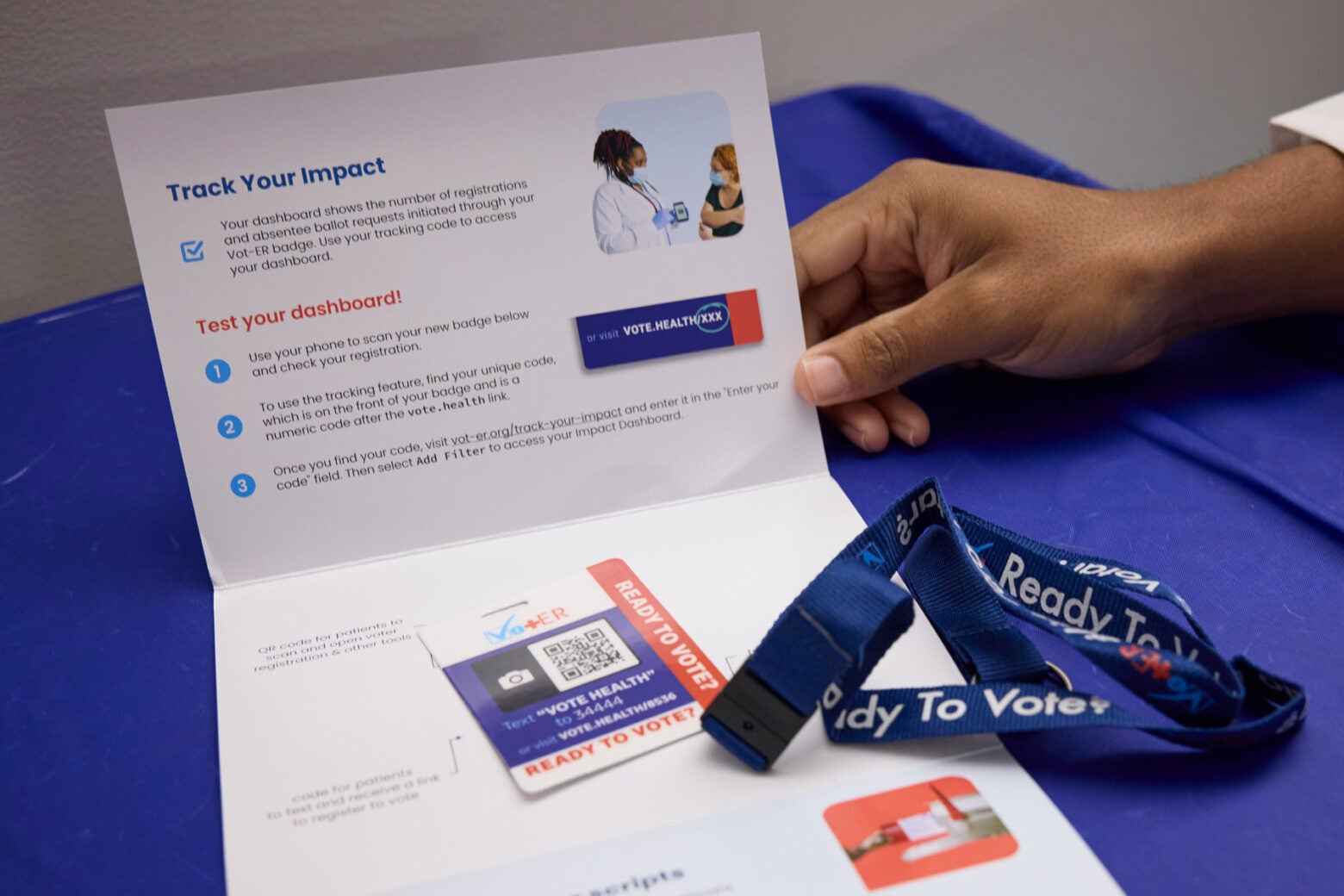

About eight months later, Martin started Vot-ER, an organization that registers hospital patients to vote. Since 2019, he has helped around 110,000 people in all 50 states the District of Columbia either to register to vote or to obtain emergency absentee ballots. He says Vot-ER expects to help another 75,000 people register before the presidential election this November—with help from 50,000 volunteer doctors, nurses, and other health care professionals at more than 700 hospitals and health care clinics. During their shifts, the volunteers wear lanyards around their necks, which feature QR codes that link to voter registration forms. Together with health facilities, Vot-ER also sends out voting reminders—more than a million so far, mostly by email or text message—and collaborates with organizations in other ways. With the Association of American Medical Colleges, for instance, Vot-ER developed a fact sheet in 2022 for medical schools and hospitals about how health care providers can talk to patients, colleagues, and students about voter registration.

Martin coauthored a study of Vot-ER’s work, published this summer in Jama Health Forum, that found the voters registered by the organization are younger and more racially diverse than those reached by traditional political campaign contacts—suggesting that health center-based voter registration could be a promising avenue for bridging the voter participation gap faced by marginalized communities.

Martin is at the vanguard of a growing effort within the public health community to get patients voting. The movement is fueled by two ideas: First, that medicine plays a relatively small part in a population’s health compared to the conditions of the places where they live. Second, the best way to improve a population’s health is to improve government policies in the areas that drive health—like pollution, unemployment, homelessness, and traffic safety (as well as, of course health care). One study found that in the states which performed best on a set of 12 public health indicators, it was also easy to register to vote—and conversely, states where voting registration is most difficult or restricted also performed poorly on public health indicators.

The American Public Health Association has named voting as one of the key “political determinants” of health. It’s a connection already well-documented in Europe, where several studies from countries across the continent show a strong link between voter participation and physical and mental health. The research is less well developed in the United States, but last year, the Department of Health and Human Services named increasing voter participation one of its goals for improving population health by 2030—a move officials connected to the link between health and voting.

For Martin, the link is simple: Better policy won’t pass unless enough politicians care more about the people who are getting sick. Turning more ER patients into voters is a first step to making that happen.

“I’m an emergency department doc at the end of the day, and I’m sorta wired to run into burning buildings with my cape on,” Martin says. “But that approach isn’t sustainable for a health care system—nor for society. The goal here isn’t just to put out fires but to eliminate the conditions that spark them in the first place.”

Signs throughout Massachusetts General Hospital's emergency department encourage people to register to vote.

Alister Martin displays the kit his organization, Vote-ER, sends to hospitals around the country to help hospital staff register patients to vote.

As a resident for Massachusetts General Hospital in 2019, Martin felt frustrated at what he describes as the game of “whack-a-mole” that the hospital was forced to play when it came to the patients who needed the most help—many of whom struggled not only with addiction but with other overwhelming problems, like homelessness. “I’d seen us discharge patients with no housing and no options, nowhere to go, when it was four degrees outside,” Martin explains. “I spent a lot of time creating programs that helped patients overcome addiction, and I still advocate strongly for these interventions. But what happens when we fail to secure stable housing for those patients? What does living on the street with little hope do for patients’ chances at long-term recovery, even if we were able to get them started on treatment?” Vot-ER was the culmination of his effort to bring together his interest in healing patients with his interest in creating a better health care system.

Linking voting and health has caught on elsewhere, too. AltaMed Health Services, a network of 67 health centers across Los Angeles and Orange counties, educates its half-million patients, who are primarily Latino and Latina, about health-related ballot initiatives. Ahead of the midterm election in 2022, for example, AltaMed distributed a brochure summarizing arguments for and against a California law banning flavored tobacco products and an amendment to the state constitution that would protect the right to an abortion, among other ballot initiatives. About 25 percent of its health care centers also serve as flexible voting sites, in conjunction Los Angeles County Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk’s office. More than 1,800 people have cast ballots through those sites since 2020.

In Providence, Rhode Island, another medical resident, Kelly Wong Heidepriem, began another voter initiative in 2018. While an intern at Brown University’s Warren Alpert School of Medicine, she began helping patients unexpectedly hospitalized on voting day to obtain emergency absentee medical ballots. The ballots were so infrequently used that even elections officials didn’t know how the process worked. Her organization, Patient Voting, eventually expanded its focus and, last year, merged with Vot-ER.

The assumption that voting can affect policies that impact people’s help seems to suggest that people cast their ballots with their health in mind—or even, perhaps, that they tend to vote for specific policies, or even political parties. There’s no data suggesting partisan leanings of voter registration so far (although the Republican National Committee earlier this year raised the specter, without evidence, of election-meddling). But three conservative medical groups contacted by Harvard Public Health expressed no concern. “I have no objection to encouraging people to vote as long as there is no political agenda pushed,” says John Edeen, a pediatric orthopedic surgeon in San Antonio, Texas, who serves as membership director for Doctors for Responsible Gun Ownership.

Of course, registering people to vote is not the same as getting people to cast ballots, and these initiatives are too young to have clear track record on whether or how their efforts sway elections. An ongoing randomized trial of Vot-ER is evaluating the voting behavior of people who registered in health facilities to find out how health care-based voter registration compares to more common methods, like registering at the DMV or in a town or city office. Martin hopes the votes cast by people his organization registers will impact local policies especially—where so much of what affects health is lived out, and where even a relatively small number of new voters can change policy outcomes.

Ultimately, he wants to use regular health care visits as “opportunities for civic empowerment, particularly focusing on reaching historically underrepresented communities in rural, urban, and all other regions of the country,” he says. “In the end, a healthy democracy requires participation from everyone, and that’s what we focus on.”

Top image: Alister Martin displays a QR code volunteers with Vot-ER wear on lanyards around their necks. The code links to a voter registration form.