Feature

How a deadly global crisis went unseen

This story was originally published by Undark. It was supported in part by the Pulitzer Center.

On a rainy November evening in 2021, a Congolese researcher took a call from a concerned American friend and mentor looking for assistance on a life-threatening mission. He needed help with a delicate investigation into deaths in Central Africa.

The researcher, a seasoned humanitarian worker and development project evaluator named Karume Baderha Augustin Gang, had collaborated with the American epidemiologist some 20 years back, when he helped conduct a mortality survey that revealed millions of deaths during a war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In retaliation for Karume’s involvement in that project, opposition forces had tortured the young researcher’s brother. But despite the risks of a similar investigation, Karume agreed to take part.

Official U.N. and World Bank statistics rank the Central African Republic among the bottom 10 nations in the world in terms of its economy and health, with indications that it is improving.

Courtesy of Undark

Once again, the task was to assess mortality—this time in the Central African Republic, a land-locked country the size of France, just north of the Congo. Violence perpetrated by armed groups, national soldiers, and the Russian state-funded military company the Wagner Group had eroded stability in recent years, but no one really knew the toll that took on lives. According to the survey that Karume and his colleagues went on to conduct, the mortality rate was shocking. Published in the journal Conflict and Health last April, the report suggests that the world’s deadliest humanitarian crisis in 2022 was not in Afghanistan, Ukraine, or other places featured regularly in the news—but in CAR.

The Central African Republic has neither reliable birth and death registries nor regular censuses. To figure out how many people were dying, Karume’s team traveled by car, boat, motorcycle, and foot to conduct interviews across the country. When they analyzed their survey data, they estimated that nearly six percent of CAR’s population died within 2022, in a country with a median age around 15. Scaling for population size, this toll would amount to a loss of more than two New York Cities. And yet, the world outside of Africa is barely aware that CAR is a country. The title of the team’s report asks: “How can we not know?”

A mother beside the freshly dug grave of her 6-year-old daughter, who died of malaria. The mother could not afford enough medicine to treat the child promptly. The family eats one meal a day and the mother says she worries about her other children dying without adequate treatment.

Courtesy of Undark

The most proximate explanation is that the United Nations estimated a drastically lower death rate in CAR in 2022, four times smaller than the survey’s result. The U.N.’s frequently cited figure relies on statistical predictions derived from fragmented data collected several years earlier, rather than current, on-the-ground information. It is a difference with consequence. The U.N.’s mortality estimate in CAR does not merit the internationally accepted definition of a humanitarian emergency: namely, at least one death per 10,000 people per day. The rate in the new study exceeds that threshold. Such definitions matter because emergency declarations spur fundraising, international aid, and political pressure.

Experts who specialize in crises call the survey by Karume and his colleagues sound, and say they’ve encountered such disparities before. In fact, it’s a long-standing problem during times of war in the world’s poorest and most fragile regions, such as in South Sudan, Congo, and, now, in CAR, when the U.N. and other government-affiliated organizations resort to mathematical models because data collection is impeded by unpredictable violence, degraded roads, and a lack of connectivity by internet and phone. Courtland Robinson, a demographer at Johns Hopkins University, said of the study, “We’re on good, solid ground to say there’s a crisis here that is not adequately recognized.”

“We’re on good, solid ground to say there’s a crisis here that is not adequately recognized.”

Courtland Robinson, demographer, Johns Hopkins University

However, the CAR government and Patrick Gerland, a chief demographer at the U.N. population division responsible for the organization’s estimates, have been skeptical of the study’s results. If such a massive crisis occurred in the digital age, Gerland said, the outside world would know and respond. “Why does it look like an invisible situation?” he said. Humanitarian experts question such assumptions because most of CAR’s population lacks internet access, as well as outside connections able to amplify reports. As a result, the barrage of updates, photos, and videos streaming out of places like Ukraine, Israel, and Gaza does not exist.

Remarking on the world’s sympathy and attention to suffering in these regions, Karume wonders why crises on his continent can’t muster a fraction of the concern required to deliver food, health care, and peace. The team’s perilous study has mainly been met by silence. “In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in Somalia, in the Central African Republic, in South Sudan, we wonder, are we so different?” he said. “Do we have blue blood and do others have red blood?”

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

When seasoned humanitarian workers talk about CAR, they often recount ominous observations: a lack of young children, undocumented graves, and attacks on clinics, to name a few. Official U.N. and World Bank statistics rank the country among the bottom 10 nations in the world in terms of its economy and health, with indications that it is improving. But experts view such numbers skeptically because the same problems that make life hard in CAR also obstruct record-collecting. “Official numbers only scratch the surface,” said Lewis Mudge, the Central Africa director at Human Rights Watch, an international research and advocacy organization. “So many people are suffering there.”

“CAR is a whole other category,” Mudge said. “They say Burundi has the highest poverty, but you can get to every corner of Burundi with a vehicle and on foot. In CAR, there are places you can’t get to, except for on a river.” Communities often live far from medical care and markets, places where information might be recorded. Disease outbreaks happen and aren’t reported.

To this fractured geography, add war. More than a decade of violence has killed and injured droves of civilians and driven more than 1.4 million people from their homes—a quarter of the country of roughly six million. Without stability, hospitals and schools can hardly function, crops can’t be harvested, and roads fall apart. Women give birth without health care, or light at night.

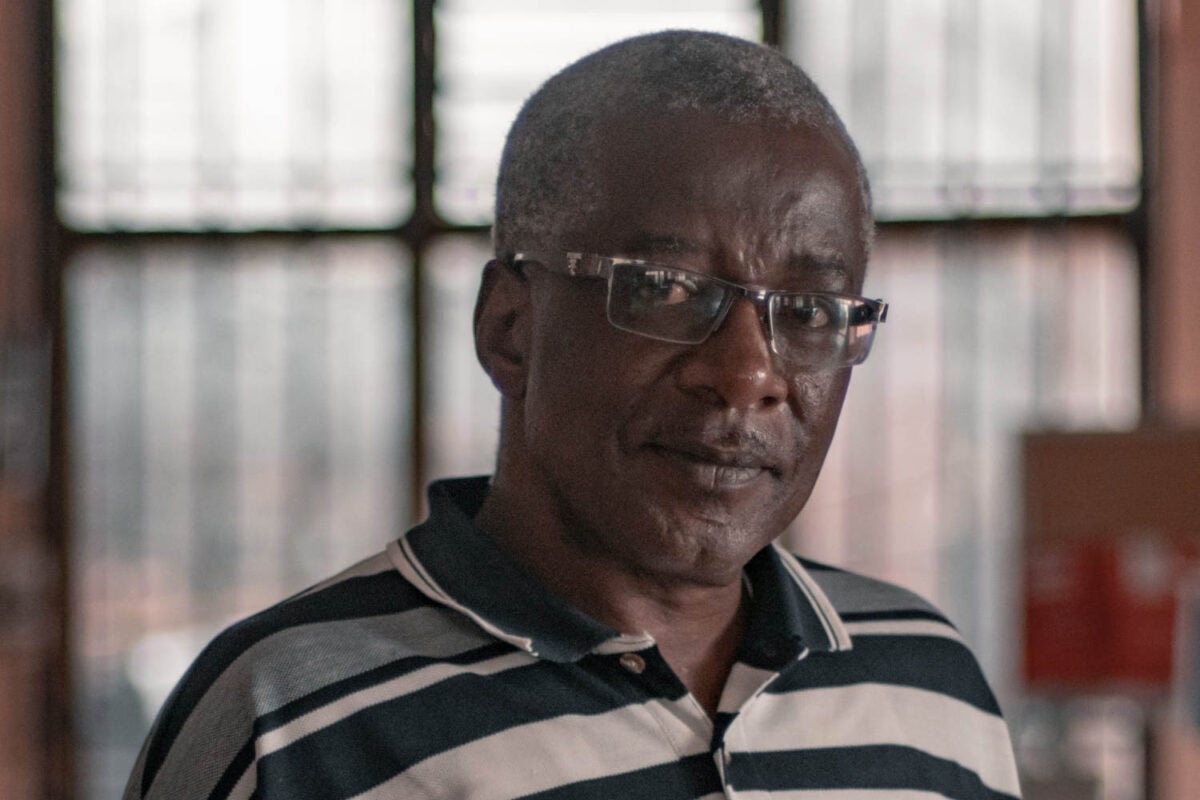

Congolese researcher Karume Baderha Augustin Gang conducted a survey across the Central African Republic in 2022, finding an astronomical death rate outranking Ukraine, Venezuela, and other countries regularly featured in the news. “Can you tell me why they should not deserve attention?” he asked.

Guerchom Ndebo for Undark

An armored vehicle belonging to United Nations peacekeeping troops is parked outside of a base in Bangui. Although the mission has been active in the Central African Republic since 2014, civilians continue to be attacked.

Courtesy of Undark

“One day, you will come back, and you won’t find anyone here because the problems will have killed us all,” a mother told staff with Médecins Sans Frontières, or Doctors without Borders, in 2018, according to the organization’s dispatch from Ouaka, a CAR district shaken by repeated rebel attacks. The medical aid group wanted to know if the suffering they saw was worse than official statistics suggested. So, in March and April of 2020, it led a small survey to find out how many people in Ouaka had died that year. The study revealed a stunningly high death rate, quadruple the nationwide estimate from the U.N.

One researcher involved with that study, Columbia University epidemiologist and emeritus professor Les Roberts, had a long history of putting numbers on invisible crises through mortality surveys. He worried that Ouaka was not exceptional but reflected deteriorating conditions across the country. Rebel groups attacked the capital city of Bangui in 2021, and CAR’s leadership increasingly turned to the Wagner Group for weapons, military training, and defense. Although the Russians maintained a degree of order in Bangui, the U.N. and Human Rights Watch also linked the group to mass executions, torture, and the forced displacement of civilians.

Beyond Bangui, the situation was murky because the government threatened local journalists and prevented international reporters from traveling outside of the city. Reports from aid workers in rural areas dwindled as groups shut down operations in the wake of hundreds of attacks on humanitarians. Large government-affiliated organizations typically entrusted with nationwide surveys—such as UNICEF and the U.S. Agency for International Development—often have security provisions that require them to avoid particularly dangerous territories or travel in military-style convoys with armed soldiers. As a result of such measures, along with impassible roads, a comprehensive, nationwide survey hadn’t been conducted in CAR for more than a decade. (Gerland, from the U.N., suggested another would cost around $1 million.)

In contrast to large agencies, Roberts is renowned for smart and scrappy surveys that rely on teams of interviewers who travel by car, motorcycle, and foot. Determined to carry out such a survey across CAR, Roberts propositioned Karume on that November evening. Karume had worked in CAR previously, agreed that Central Africans might be in trouble, and wanted to bring such suffering to light. He was in.

Their next move is disputed: Karume and Roberts said the CAR government and ethics board deflected and ignored their repeated requests for permission in 2021 and 2022. The CAR government maintains that no such requests were made. Anxious to start, Karume vetted the study with the Congolese health ethics committee, who authorized it immediately.

With that, the researchers mapped out areas across CAR that would lend them a representative sample of the country. Balancing a drive for large numbers with a responsibility to ensure the team survived the mission, Roberts aimed for data from at least 4,000 people. Jennifer O’Keeffe, an epidemiologist who had worked in conflict zones around the continent, now at Johns Hopkins, joined the team. And Karume set about recruiting Central Africans who spoke local dialects and understood terrains beyond roads and the rule of law. With consent from local leaders and interviewees, team members would ask scripted questions: How many people who live in this household have died since January? Did they sleep under this roof most of the 30 days before they died? “We went above and beyond to get an accurate number of deaths for each household,” Roberts explained.

Reaching households turned out to be the hardest part. Before heading into one town held by rebels, one of Karume’s local contacts warned that motorcycle drivers “from outside” would be killed and their bikes stolen. “What I’ll do is give you former combatants who are now motorcycle taxi riders. Everybody knows them, and they’ll take your guys,” his colleague offered. Karume accepted, and stayed behind while Central African interviewers went on without him. “They sampled the town in two days and came back,” he said. “That is heroism.”

Without stability, hospitals and schools can hardly function, crops can’t be harvested, and roads fall apart. Women give birth without health care, or light at night.

“We took a great risk,” said one Central African researcher involved with the study. He and others who assisted in the study requested anonymity due to fears of retribution for their work exposing violence in their country. His descriptions of Russian-speaking White men presumed to be part of the Wagner Group—and need for anonymity—are corroborated by troubling investigative reports. In 2022, for example, Human Rights Watch documented a harrowing incident involving a shop owner named Mahamat Nour Mamadou. Russian-speaking forces detained Mamadou, hit him with iron rods while his ankles were cuffed, kicked a brick in his mouth, and cut off his pinky finger with a knife. Months after being released and speaking to the press about his arrest, Mamadou was killed.

More than violence, however, the team was struck by the suffering that resulted from chronic conflict: a dearth of clean water, food, medicine, and infrastructure required for survival. Climate change compounded instability. Farmers explained how delayed seasonal rains and floods killed their crops. “In some remote villages, people are not hungry—they are starving,” the anonymous researcher told Undark. “By the grace of God, the situation is very bad.”

Karume was taken aback, too. In distant towns, he saw individuals hobbling on twisted legs, their feet pointed inwards. This paralytic disease of malnutrition, known as konzo, occurs when people subsist almost entirely on the starchy cassava root. Digestion can break down small amounts of cyanide in the roots—but only if people have protein in their diets.

Some interviews ran long. Karume lingered with a woman whose husband had recently died. She and her teenage daughter often went without food all day, sparing what little they had for the three youngest children. Karume paused to brainstorm ways to earn a living. Maybe she could sell cassava flour? It was hard to listen without offering help. “I don’t know how to express it,” he said. “It broke my heart.”

When the numbers were in, the team found that violence wasn’t the most common cause of death, although the team blamed it for indirectly eroding living conditions. The country appeared to be on the brink of famine, with 82 percent of adults and 73 percent of children eating only once a day or not at all. Malnourishment renders people vulnerable to ailments. And a lack of basic health care means they die from curable conditions, like malaria and bacterial infections. Nearly a fifth of deaths were attributed to malarial fevers. Diarrhea and vomiting accounted for 9 percent of deaths. Violence comprised 6 percent.

Meeting around a table in Bangui, the team agreed they needed to sound an alarm and press for urgent food and medical aid. If altruism doesn’t move powerful countries to act, Karume suggested self-interest should. Chronic conflict and dire poverty drive mass migration. And desperation fuels recruitment for terrorist organizations growing in Central Africa. “Why wait until people are trying to flee or become bomb-droppers,” he asked.

The team’s second shock was the dramatic difference between its mortality rate and the U.N.’s. Death tolls in conflicts and natural disasters often vary by several thousand, as demonstrated by disagreements on the death toll of Palestinians due to Israel’s ongoing attacks on Gaza. But if the researchers’ study was accurate, it implied that the U.N. discounted roughly 190,000 lives lost in CAR in 2022. “United Nations statistics are often wrong, but we had never seen them this wrong,” Roberts said. “This is the worst example I’ve ever seen, and I have spent my career in chaotic warzones.”

Researchers who study mortality in crises, who weren’t involved with the CAR study, call it credible. They find the survey’s sample size smaller than ideal, but sufficient given the care the team took to include different parts of the country, rather than sticking to safe zones or overrepresenting those known for violence. “The crux is the sampling and I’m confident with that,” said Gilbert Burnham, the founder of the Center for Humanitarian Health at Johns Hopkins University. Bradley Woodruff, an epidemiologist specializing in humanitarian emergencies, agreed. In an email to Undark, he wrote, “I see no source of obvious bias which would tend to invalidate the results.”

In addition, human rights investigators found it easy to believe that U.N. estimates might be wildly off in CAR. Nathalia Dukhan, a senior investigator at The Sentry, an organization that tracks war crimes in the country, said, “I think the study is probably closer to reality than what the U.N. tells us.”

Dried fish are sold at a small stand in Bangui. They are a common source of protein for many living in the Central African Republic.

Courtesy of Undark

A child in the Central African Republic holds a bowl of ground cassava roots on his head.

Courtesy of Undark

Women buy and sell food at a bustling market in Bangui. People in many rural villages live far from such markets, which limits their food supply and income.

Courtesy of Undark

Cassava is often the only food for poor families, who live off the leaves and a flour ground from its starchy roots (pictured). Without protein in their diets, people subsisting on cassava roots alone are at risk of a paralytic disease called konzo.

Courtesy of Undark

Most U.N. estimates on mortality rates, fertility rates, life expectancy, and more are produced by the agency’s population division in New York City. From his office in Manhattan, Gerland, the demographer who heads the population estimates division, patiently explained how they crunch numbers collected by others. In most upper- and middle- income countries, they draw from national censuses and birth and death registries. When those aren’t reliable, they assess nationwide surveys typically conducted by other U.N. or governmental agencies. And when nationwide surveys don’t occur, the division looks for scraps—older or more limited nationally representative surveys—and then applies statistical models to extrapolate current numbers. Such is the situation in CAR.

To arrive at their 2022 mortality rate for CAR, the U.N. division looked to the past. The most recent survey they used is a 2019 study of childhood mortality by UNICEF. Gerland explained how demographers estimated numbers of adults based on orphans counted in that report, and applied statistical models to predict yearly death rates, based on past trends. For example, if the number of children dying dropped by, say, 5 percent for several consecutive years, statistical models expect it to do so again. A glaring caveat is that trends assume stability. “We are conscious that this kind of data is imperfect,” Gerland conceded.

Because conflict tends to be unpredictable, Gerland explained how the division incorporated data from a U.S. organization that counts fatalities in battles, explosions, and political violence around the world, called the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, or ACLED. Analysts at the group pick over a flood of online news, social media, and reports from organizations on the ground. Cellphone footage has transformed how it and the broader world witnesses and responds to everything from police violence to war. But online information is inherently biased: Only about 14 percent of people in CAR have access to electricity—most of whom are concentrated in the capital city—and just 10 percent can connect to the internet. “Very few people appreciate how bad surveillance is in the world’s poorest countries,” Roberts said.

Roberts leaves his home in New York to study death in places like this, where communities cannot easily alert people outside of a crisis for technological reasons and because they lack international connections. To show how networks influence the visibility of a problem, he once tasked graduate students at Columbia University with ranking the level of violence in five nations—CAR, Mali, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen. Based on what they found online, the students put Venezuela at the top. In fact, the country should have been at the bottom of the list. Roberts’ colleague put the same question to students at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and got the same result. In a report on the experiment, they wrote that a lack of connectivity to the outside world helps account for disparities in aid. During the Kosovo War, the Balkan country received about 20 times more in humanitarian assistance than the Congo during its concurrent conflict.

What’s more, death counts from attacks and explosions tend to miss untold numbers of individuals who fled and met their demise. “You don’t count all the people who die in the bush because of hunger and sickness—because of no shelter, babies die,” said The Sentry’s Dukhan. “Nobody is really aware of the aftermath.”

“United Nations statistics are often wrong, but we had never seen them this wrong.”

Les Roberts, Columbia University epidemiologist and emeritus professor

Inevitable inaccuracies aside, Gerland called the new survey’s mortality rate “astronomical,” “not realistic,” and “impossible,” in interviews with Undark last year. Like many demographers, he sees every year as part of a continuum, and the figure didn’t jibe with the division’s descending slope of annual mortality rates since the country’s independence from French colonizers. If death rates in 2022 are quadruple agency estimates, Gerland said that the years before and after must be far higher, as well. Given already dismal death rates in the country, such a trend would lead to the disappearance of the entire population. “I want to believe that, first, it didn’t happen at this magnitude,” Gerland said. “And that if it did, more people would be aware and would react.”

Roberts called this statement ironic in the face of a report meant to grab the attention of the U.N., the gatekeepers of a humanitarian response. He pointed out that the notion of the country disappearing assumes that the death rate in 2022 is continuous, when the word used in the report’s title—crisis—means a deviation from the norm. In fact, the team’s data suggest a dark turn after the 2019 UNICEF survey. A figure showing the population’s breakdown by age illustrates a dearth of children younger than 3, compared to those who are older, in a country where very few women have contraceptives. Severe stress and malnutrition are linked with infant mortality and low birth rates. Disappointed in Gerland’s response, Roberts added, “The U.N. population division lives on computers and builds a world of assumptions.”

Burnham, from Johns Hopkins, puts more weight in Roberts’ mortality estimate than the U.N.’s. The agency’s approach is adequate most of the time, he explained, but problematic in places like CAR, where stiff security protocols impede national surveys. “It is not an easy job,” Burnham said. “Interviewers have been killed, have been put in prison. It’s not like asking people, ‘What is your favorite kind of soap?’”

Further, the U.N. is comprised of countries, and its agencies work closely with governments to improve how they serve their citizens. It’s a laudable goal that occasionally backfires when governments have vested interests, Burnham said, such as discounting their own violence or neglect. “Independent assessments of mortality are the gold standard in these situations,” he said. “In public health, you get criticism for numbers people don’t like.”

Gerland fiercely rejected the notion that he and his colleagues are swayed by political opinions. “I am not saying the U.N. is perfect,” he added, “but then why is everyone else missing this situation, too?”

Still, after multiple interviews with Undark, and an editorial calling for aid to CAR in reference to the survey, Gerland and Roberts spoke about it. Gerland then committed to incorporating the study’s findings into the U.N. mortality estimate for CAR in the coming year. To date, however, its 2022 figure remains the same.

Roads flood in the rainy season, complicating everything from research to the delivery of medical supplies. Above, men walk barefoot on a flooded road in Bangui.

Courtesy of Undark

A person with severe malaria receives an intravenous injection of an anti-malaria drug at a small shop in Bangui, rather than at the hospital where care is better but more expensive.

Courtesy of Undark

Do numbers really matter? Enough that Karume experienced trauma in their pursuit. In 1999, he volunteered to interview people in a survey spearheaded by Roberts, then at an aid organization, the International Rescue Committee, to quantify death as violence flared in eastern Congo. Now known as Africa’s World War, the long-ignored conflict pitted Rwandan forces and their allies against the Congolese government. When an opposition group caught wind of Karume’s work, he said they imprisoned his younger brother for 110 days: “They even tortured him. They removed two teeth.”

The memory still stings but Karume became committed to such harrowing research when he witnessed the world’s response to their surveys revealing that some 2.5 million people had died due to conflict and its aftermath in eastern Congo between 1998 and 2001. Newspapers and policymakers decried the emergency, fueling a wave of international aid and pressure for a peace accord. It helped that the Congolese government publicized the survey results, Karume noted, which advanced their political goals. That would not be true of his survey in CAR.

“This study is shit,” Pierre Somse, the CAR minister of health, said on a phone call with Undark—a raw version of his online statement denouncing the survey in June of 2023. Somse is a doctor and researcher respected in the global health community. He recalled meeting Roberts in Bangui sometime in 2020 or 2021 but said he didn’t hear from Roberts again until the researcher told him about his soon-to-be published survey. Shocked that international researchers proceeded without consent from him or the country’s scientific ethics board, he asked Roberts, “You are publishing a study that I don’t know about?”

Roberts told Somse that the Wagner Group might be partly responsible for a surge in deaths in CAR. That accusation is rooted in bias and not science, Somse explained. As with other government officials, he maintained that the Russians protect CAR from rebel forces. Although Roberts’ survey cannot distinguish Wagner’s effects on mortality, the report nonetheless suggests, “the efforts of the Wagner mercenaries at least contributed to increased difficulties of survival.”

Months after publication, The Sentry referenced this notion in a June 2023 investigation accusing the Wagner Group of state capture in CAR. Reports of human rights violations prompted the U.S. government to sanction gold- and diamond-mining companies in CAR that finance the Wagner Group later that month, and U.S. President Joe Biden moved to exclude CAR from an international trade deal. Somse interprets Roberts’ survey in the context of rising U.S. aggression against nations cooperating with Russia, reminiscent of Cold War politics that made the so-called Third World a pawn in geopolitical wranglings. “Everyone that gets along with Russia is stigmatized,” Somse said. “We are very isolated and blamed. And here, he makes this accusation without any evidence. This blame makes the situation worse.”

In July of 2023, the CAR ethics and scientific committee sent a letter to the editor of the journal Conflict and Health, requesting the study’s retraction since the authors didn’t obtain the group’s approval. Failure to do so is a breach of scientific norms, Somse said. Of Roberts, Somse added, “I believe this is a bad scientist and I would not like to have him in my country anymore.”

Editors at Conflict and Health declined to retract the CAR study and added a note to the online report: “The sensitive nature of the work conducted meant that it was justified.” Robinson, the Johns Hopkins demographer who serves on the university’s ethical review board, explained how researchers who study humanitarian crises have a responsibility to follow-up on concerns about hidden populations, “who, absent government approval, may have no documentation, and almost because of that lack of approval, may be even more at risk.”

Robinson rattled off regions where such a rule might apply, such as in North Korea, Syria, and Myanmar. “I did some work in Myanmar, years ago,” Robinson recalled. “The moment some of those studies came out, the government in Yangon said, ‘They’re siding with the enemy, how can you trust them?’”

Burnham agreed. In 2006, he and his colleagues published a controversial study estimating that the number of deaths following the U.S. and British-led invasion of Iraq was 10 times larger than figures cited by the U.S. government. Then-President George W. Bush said the report wasn’t credible. And a spokesperson for former U.K. Prime Minister Tony Blair called the study’s figure nowhere near accurate. “We had four heads of state denounce this in the same week,” Burnham said. “I was a bit annoyed, but I wasn’t surprised.”

According to data from 2020, women in the Central African Republic are about 35 times more likely to die of pregnancy and delivery complications than those in the United States; compared to women in the European Union, the maternal mortality rates in CAR are roughly 100 times higher. The country’s soaring maternal mortality rates are due to years of conflict and political instability, a lack of health care, and unsafe abortions.

Courtesy of Undark

The 2022 mortality survey found a dearth of young children under age 3 in the Central African Republic, an ominous sign that infant and fetal deaths were rising, perhaps due to violence, malnutrition, and extreme stress for mothers, among other causes.

Courtesy of Undark

What has gotten lost in the squabble is Karume’s plea for urgent food and medical assistance for CAR. He wished the U.N. and the CAR government had responded to their study with urgent distress and vocal concern that official numbers might be eclipsing an emergency. Presumably, he said, large, international organizations have the money and technology to confirm the team’s results with another survey.

If powerful countries had any attention to spare when the team’s study was published last April, Karume fears it is now spent on the growing conflict in the Middle East. To the list of why CAR goes ignored, add its lack of geopolitical and financial consequence. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine pushed oil prices to a 14-year high across Europe in 2022, and strained wheat supplies for more than 20 countries. If conflict in the Middle East spreads beyond Israel and Palestinian territories, analysts warn of a spike in gas prices that will inflame inflation worldwide.

To further explain neglect, layer on top persistent racism against people with dark skin, a quality that excused the slave trade along the Congo River and 75 years of brutal colonization in CAR. Neglect is an injustice that Karume has pondered his entire life. Still, he did not imagine that a careful study enumerating an astronomical level of suffering would be so thoroughly dismissed. “5.6 percent of a population has disappeared! Maybe as I age, there is something I miss,” he said. “Can you tell me why they should not deserve attention?”

Top image: A mother displays a baby photograph of her daughter who died of malaria at age 6. Although the disease can be cured if treated promptly with pills, it remains a leading cause of death in the Central African Republic because of poverty and the lack of health care in many regions of the country. Courtesy of Undark.