Feature

Genomics has broad applications, and for now, broad limitations

Catalina Lopez-Correa is the chief scientific officer at Genome Canada, which funds basic and applied genomics research in health, agriculture, climate change, biodiversity—even mining. Lopez-Correa has worked in pharma and biotech in addition to the research sector and is a long-time champion of genomics. But last year, after she was diagnosed with breast cancer, she experienced genomics as a patient. She found that the transformation of cancer treatment through genomics is incomplete. She was interviewed by Harvard Public Health Editor-in-Chief Michael F. Fitzgerald, onstage at the Festival of Genomics and Biodata, which aims to bring genomics more directly into application. This interview was edited and condensed.

Michael Fitzgerald and Catalina Lopez-Correa in conversation at the Festival of Genomics and Biodata on June 12, 2024.

Courtesy of Front Line Genomics

HPH: When you started in genomics, were today’s advances—single-cell sequencing, spatial transformation—imaginable?

Lopez-Correa: The short answer is no. I mean, when I started in 2000, I don’t think we could even have imagined single-cell sequencing the way we’re doing it now: the throughput we have, the technologies we have, the reduction in costs, the applications we have in so many different sectors. It’s just an incredible development from a technological perspective. We were having so many challenges with those first sequences that real applications seemed far away.

HPH: How much shorter is the development cycle from research to seeing [genomics] in the world?

Lopez-Correa: Of course, in human health, we have so many steps that we need to follow from the regulatory aspects, the clinical trials, the validation. All those [steps] make it a very slow process in terms of utility and implementation. Whereas in agriculture [or] biodiversity, you can develop tools that can go into implementation and usage much faster. We have large-scale projects increasing yield for crops. And we have also projects in the mining sector for bioremediation [and] water treatment.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

HPH: As a scientist, what’s most exciting for you?

Lopez-Correa: All the advancements in sequencing [and] how these are really having an impact with patients. Because at the end of the day, we are here to transform health care, to transform the lives of patients—to have an impact not just from a technological and technical perspective, but from making our lives and our planet a better place. We see a whole revolution in how we’re using and implementing genomics across the world in the diagnosis and treatment of rare diseases.

Cancer is another area where we’re seeing a huge impact. [And] we’re starting to see it virtually in all therapeutic areas—metabolic diseases, neuroscience, care being driven and guided from a diagnostic perspective, treatment, prognosis. Lots of these areas are moving into prevention—what can we do to keep us healthy? This application is completely changing the health care system.

HPH: You had the experience last year of shifting into what the system looks like as a patient. You were diagnosed with breast cancer. Would you share with us a bit about how that experience has been and how it maybe changed your perspective?

Lopez-Correa: There’s a little bit of a balance between the optimistic Catalina that’s always saying in big conferences “Oh, yeah, genomics is there, genomics is here, we can use it within the clinic.” And now it’s like, “Oh, yeah, genomics is here, we can use it, and I am actually benefiting from genomics as a patient.” But there’s so many limitations about the use and implementation of it that I didn’t realize. We don’t see those challenges when we’re so immersed on the research side, or even when you’re working in a pharma company or a biotech company. You see the potential of your technology, of the great things [you]’re doing and developing. But how they’re changing the life of the patient, and how they’re having an impact in diagnosis or treatment is not always so clear. So for me, that was an eye opener.

HPH: You used the word implementation. Are you seeing the conflict of “omics” versus “ohmics,” meaning, genomics running into economic reality of getting these new techniques into the field, into the clinics, into medical education?

Lopez-Correa: I actually love that, “omics” versus “ohmics.” It’s totally right. Like, in my case, we have all these great tools for breast cancer. Breast cancer is not just one disease. There are so many classifications, so many groupings. And the treatment is different for each depending on the molecular profiling of your tumor. All these technologies and tests are available, but who can pay for them? What countries are really reimbursing for them? Who can access them? We still have a big challenge on the economic side.

HPH: Let’s drill down a little bit because, you know, I hear about the $100 genome. That sounds like a pretty good deal.

Lopez-Correa: I have been presenting these wonderful slides on how the cost of sequencing a genome [has] decreas[ed] dramatically over the years, and how this is changing our field. And yet . . . $100 a genome . . . yes. But in reality, you know, one single test like Oncotype DX, which is the standard of care for breast cancer patients, is about $4,000. So where is that $100 genome when you do a panel of 21 genes and it costs $4,000? And you have to send your sample from Canada to the US. One hundred dollars a genome basically makes it [sound] accessible to all of us everywhere in the world, not really thinking that we need to send a sample to the US, that we need to pay $4,000 and more for analysis, interpretation, reporting, and all that.

How come we don’t have technologies that are decentralized, that are really allowing for access in a more equitable way? Imagine, if this is happening in Canada, what is happening in Latin America? What is happening in Africa? Think about countries like Colombia [where Lopez-Correa was born and got her medical degree]. The approval time for a test like an OncoType DX will be about one or two months. That’s too late; that’s not actionable.

As a [genomics] community, we need to think about that more broadly. We talk about the $100 genome; we talk about single cell sequencing, spatial analysis, all these technologies. But we sometimes forget the endpoint, which is, again, changing the life of a patient—in my case, using the Oncotype DX to decide if I need chemotherapy or not. Those are critical decisions that could save the system millions of dollars and could save the patient so much pain, so much trouble.

HPH: What else as a patient has been a striking part of this experience for you?

Lopez-Correa: If you go to family doctors, if you go to nurses, if you go to some other members of the health care system, genomics remains this technology far away from them; they don’t really see the connection and the applicability. That’s a big roadblock. I knew this was a problem. But as a patient, you know, the nurses I talked to, they have no clue. Even the ones that are enrolling me to the sequencing project—they don’t know what incidental findings are.

HPH: If we compare genomics to information technology, we had our first all-electronic computer in 1946. [Now] all of us now have our computer right here [in our hands]. Where’s genomics on that spectrum?

Lopez-Correa: We have that reduction in costs. We have the portability, we have the utility, but there is still an access challenge around genomics. [In telecommunications] some countries, in particular in low- and middle-income countries, never went to landlines across the country; they moved directly to cell phones. Maybe with genomics, we can do that—come up with small, portable solutions that will address the clinical needs onsite, at the point of care, and at a much lower cost and much easier way of using it. Thailand deployed for the entire country a pharmacogenomics test in a little card that people can use. That’s really taking the technology to the next level, using it in pharmacies. They don’t need to sequence the entire population.

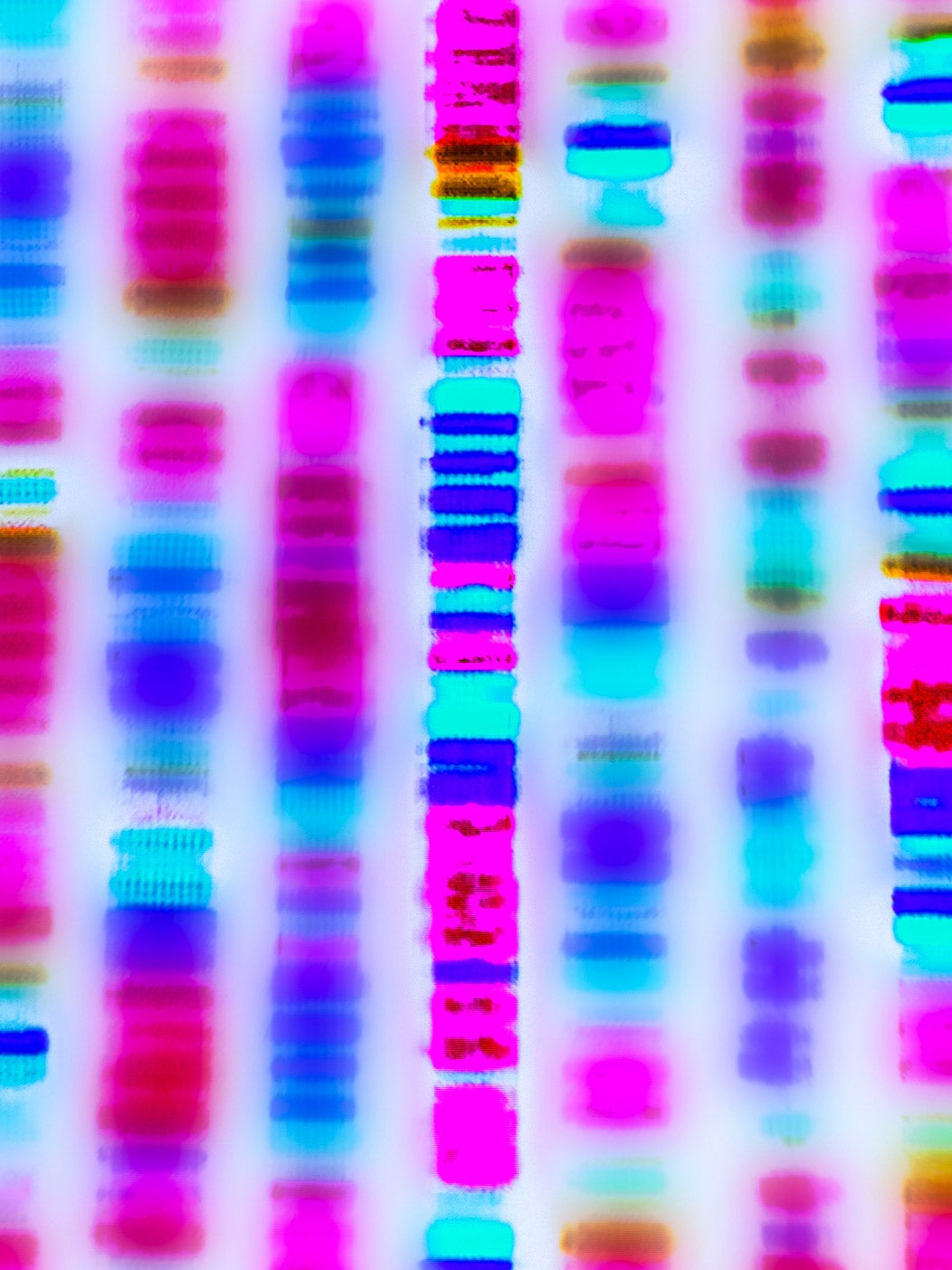

Lead image: Gio_tto / iStock