Ideas

Editorial cartoonists were early U.S. public health advocates

In the second half of the 19th century, as the disciplines of epidemiology and public health emerged, newspapers and magazines in the United States began regularly printing editorial cartoons, especially in the new weeklies such as Puck. These early cartoons often lampooned public health problems—poor sanitation, greedy developers, lax regulations—using caricature and humor to stoke outrage in readers.

Here are a few striking examples of advocacy in this new genre of graphic art.

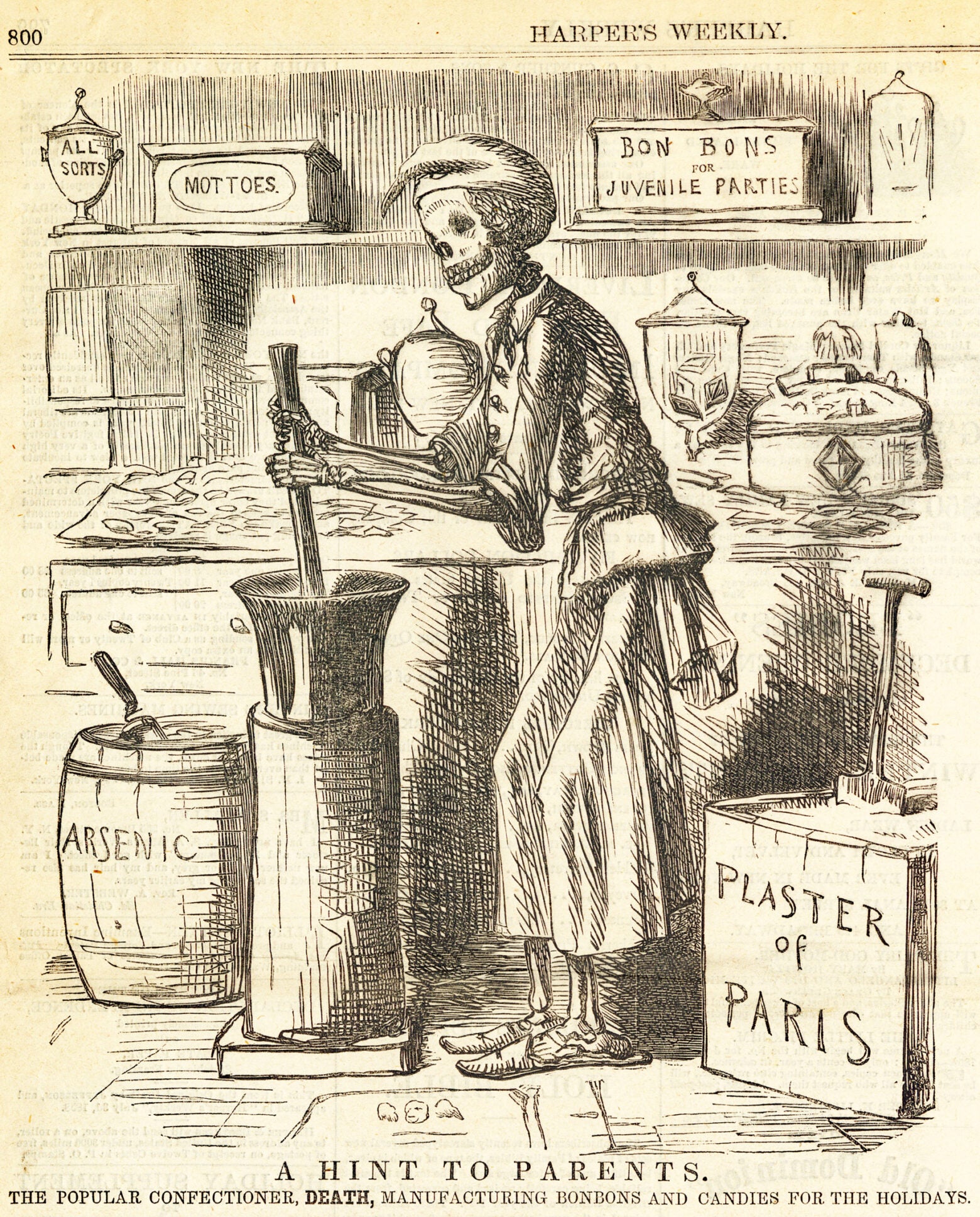

“A Hint to Parents.” Harper’s Weekly, December 11, 1858.

Candy

In the late 1800s, urbanization increased people’s dependence on manufactured foods. Manufacturers often used cheaper, potentially harmful ingredients to cut costs.

Candy makers frequently added toxic mineral additives to their products to create vibrant colors. This 1858 satirical illustration depicts Death stirring candy tainted with arsenic and plaster of Paris.

The problem was widespread. In 1884, New York City’s Board of Health destroyed over 72,000 pounds of adulterated confectionery. Despite growing awareness of these risks exposed by chemists, regulatory efforts were initially weak because businesses opposed them. The lack of food safety regulations continued until the early 20th century, when the progressive movement and works like Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle finally prompted significant reforms. In 1906, Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act, protecting consumers from dangerous food additives and establishing more rigorous food safety standards.

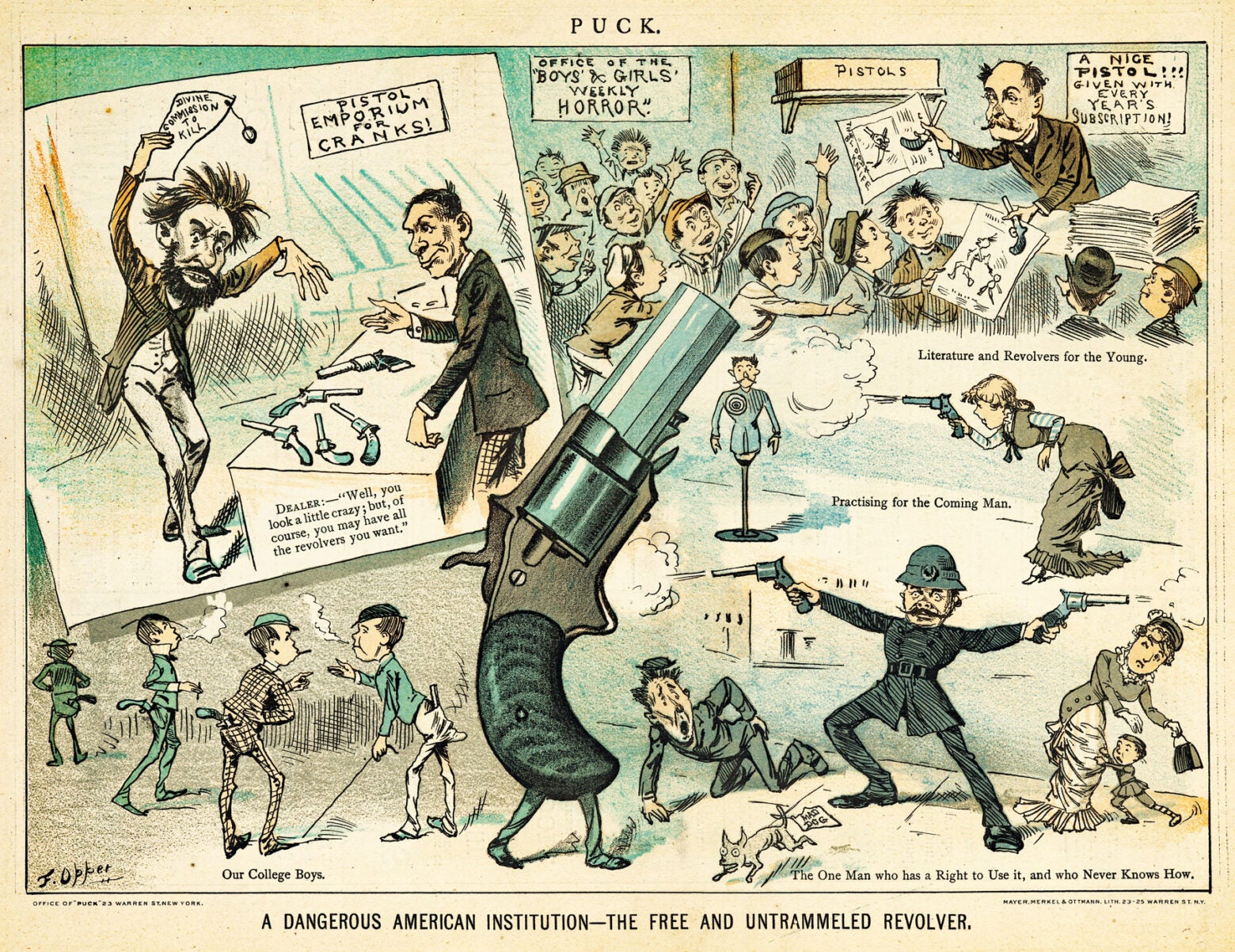

“A Dangerous American Institution—The Free and Untrammeled Revolver.” Puck, December 14, 1881.

Revolvers

The epidemic of gun violence in the U.S. has deep historical roots: Even in the 1880s, the widespread availability of guns to ordinary people was recognized as a growing threat. This danger emerged from several technological innovations in the mid-19th century.

The rotating cylinder that could hold six bullets was revolutionary when the Colt revolver was mass-produced in the mid-1800s. Before this innovation, firearms were far more cumbersome. They featured long barrels and required manually loading gunpowder and shot for each use.

The new revolvers changed everything. They had shorter barrels, rotating cylinders with multiple chambers, and used pre-manufactured bullets that combined gunpowder and projectile in a single cartridge.

These smaller weapons could be easily carried or concealed and quickly fired multiple times without reloading—democratizing gun ownership but creating new public safety risks.

The wild-haired figure in the Emporium for Cranks resembles Charles Guiteau, who shot President James Garfield with a revolver in 1881. Garfield died 79 days later from complications of the wounds. Newspapers dubbed Guiteau, who believed he was owed a consulship by Garfield’s administration, “a crank.”

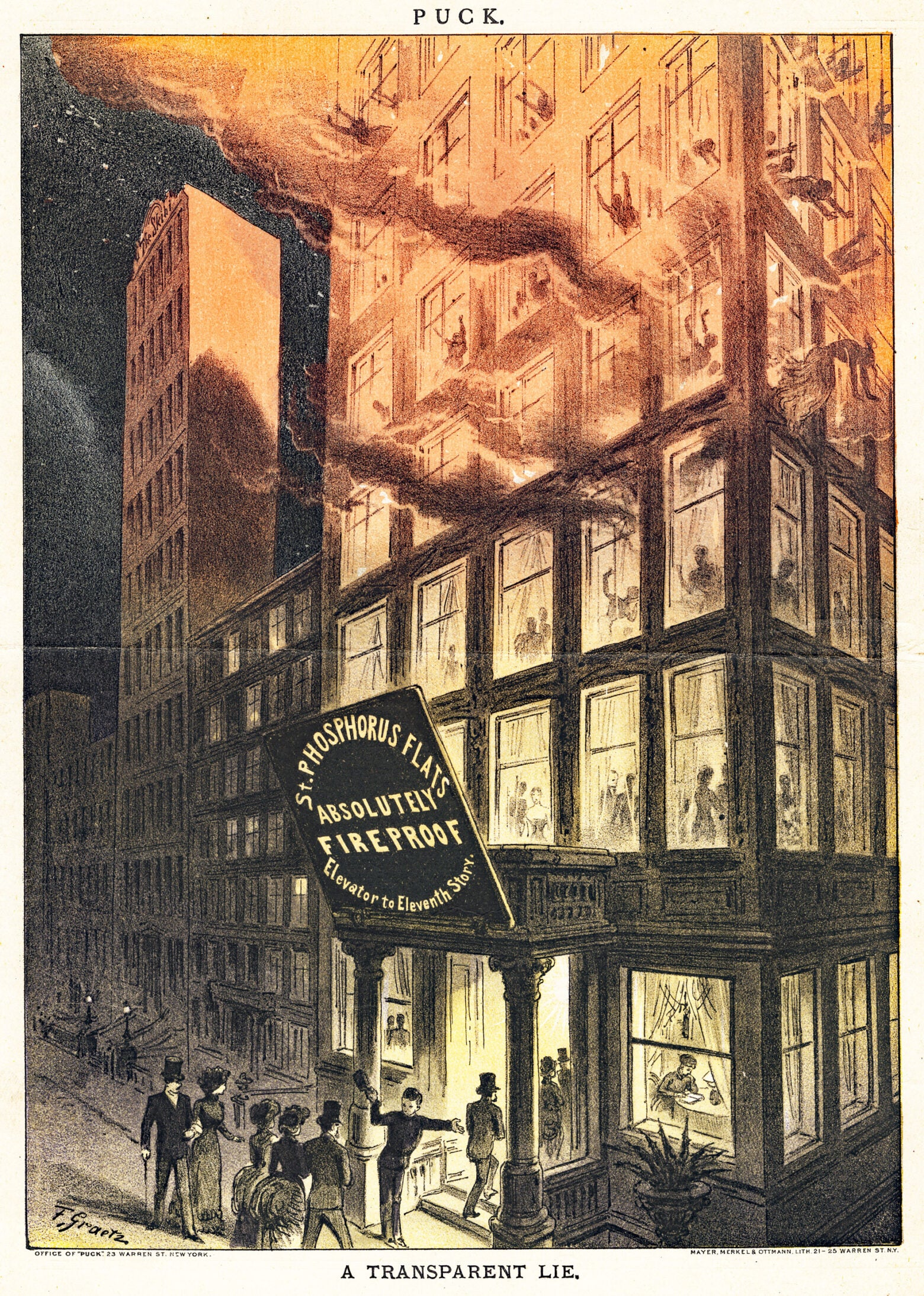

“A Transparent Lie.” Puck, April 16, 1884.

Fire

Two innovations in mid-19th century cities promised safer living: brick exterior walls replacing wooden construction, and Elisha Otis’s “safety elevator,” first installed in 1857, which prevented cars from falling. These advances lead to a boom in high-rise construction starting in the mid 1880s.

However, developers ignored crucial risks. While brick walls wouldn’t burn, wooden floors and joists remained flammable. This 1884 cartoon depicts another tragic oversight: Fire departments didn’t yet have strong enough water pressure to reach the upper floors of high-rise buildings.

Photo credits: Bert Hansen Collection of Medicine and Public Health in Graphic Art, Ms. Coll. 67 of the Medical Historical Library, Cushing/Whitney Medical Library of Yale University