Opinion

Unhoused shows us the public health crisis under our noses

An exhibition on the living might seem an odd fit for a museum best known for its collections of skulls, body parts, and medical oddities. But with Unhoused: Personal Stories and Public Health, the Mütter Museum, run by the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, is both gesturing to the college’s late-18th-century origins in fighting epidemics and signaling a possible new direction.

Elsewhere in the museum, a saponified corpse known as “the soap lady,” preserved fetuses, and slides of Albert Einstein’s brain vie for attention. Another exhibition highlights the issues of consent, provenance, representation, and medical racism that have shadowed the Mütter’s past.

In Unhoused, however, the museum’s motto, “Disturbingly Informative,” assumes a different meaning. What may be most disturbing is our failure to pay attention to the public health problem on our doorsteps.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Confined to a single gallery, Unhoused doesn’t purport to offer a definitive account of the complex links between homelessness and public health. Instead, it provides a space to contemplate individual perspectives.

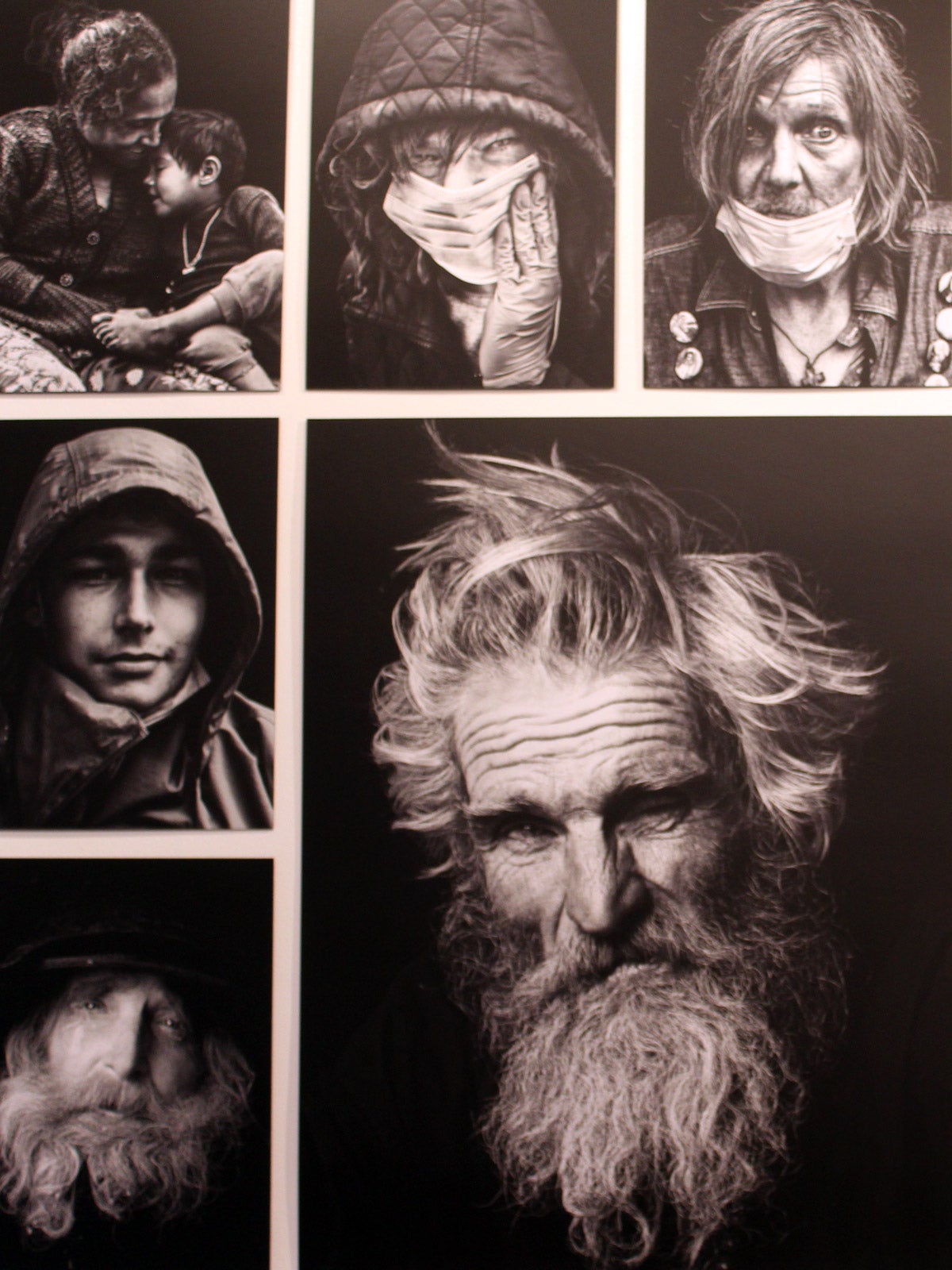

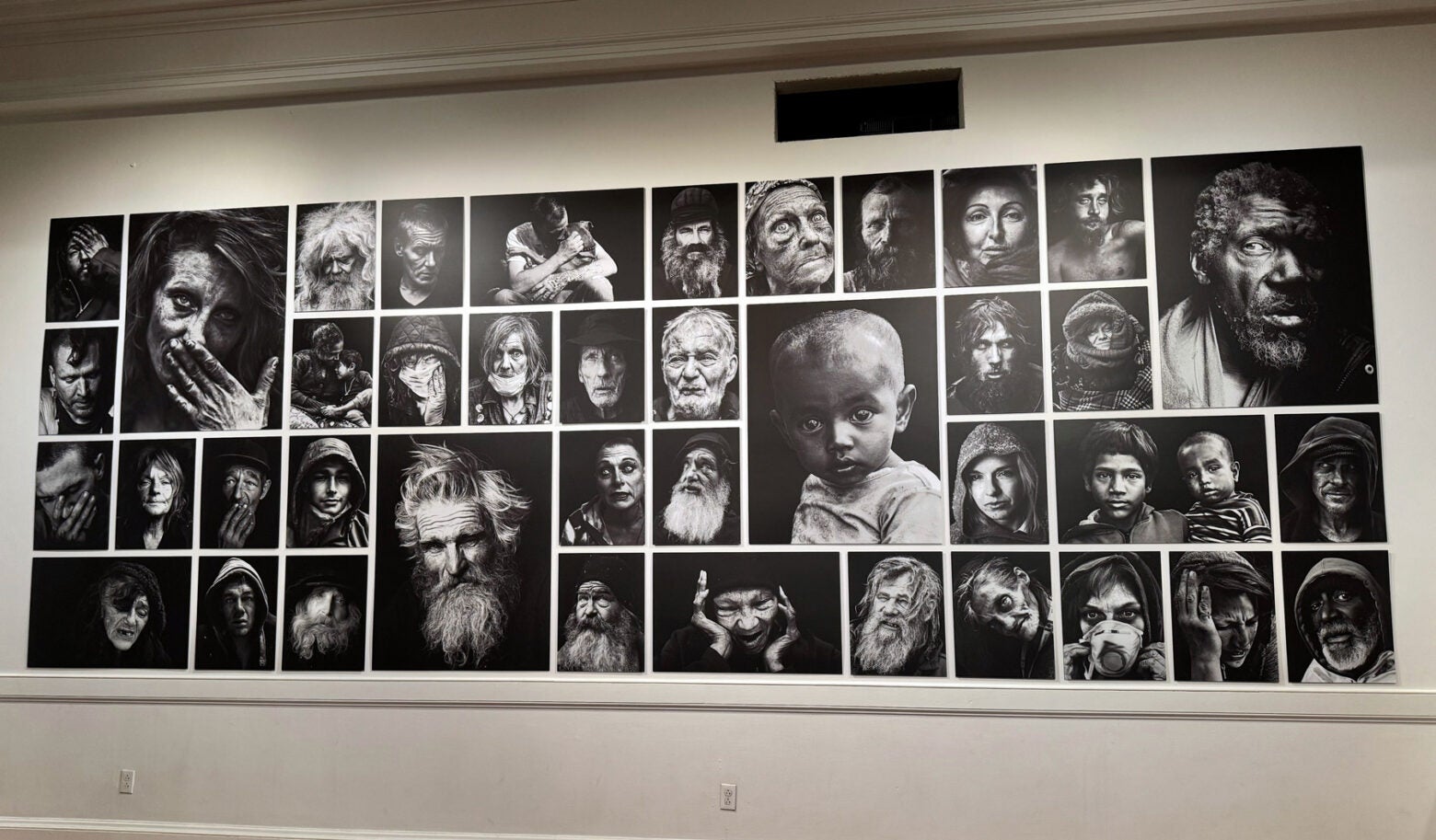

The focal point of the exhibition is two displays of art—both, in effect, collages. Leah den Bok, a Toronto-based photographer, supplies 40 large, exquisitely detailed black-and-white portraits from an ongoing project she titles Humanizing the Homeless.

Photographs from Leah den Bok’s project “Humanizing the Homeless” displayed at the Mütter Museum’s exhibition, “Unhoused: Personal Stories & Public Health.”

Courtesy of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

Set against black backgrounds, den Bok’s subjects, ranging from a two-year-old to a man in his 80s, are grimy, occasionally wild-eyed, often visibly sad. They can seem lost, or confrontational. Some face the viewer directly; others look away. A catalog offers quotations and bare-bones background information from interviews conducted by the photographer and her father, Tim den Bok. (It would be better if key quotes also were highlighted via wall labels.) The men and women, from Canada, the United States, India, and elsewhere, talk of family cutoffs, drug addiction, mental illness, and the challenges of life on the streets.

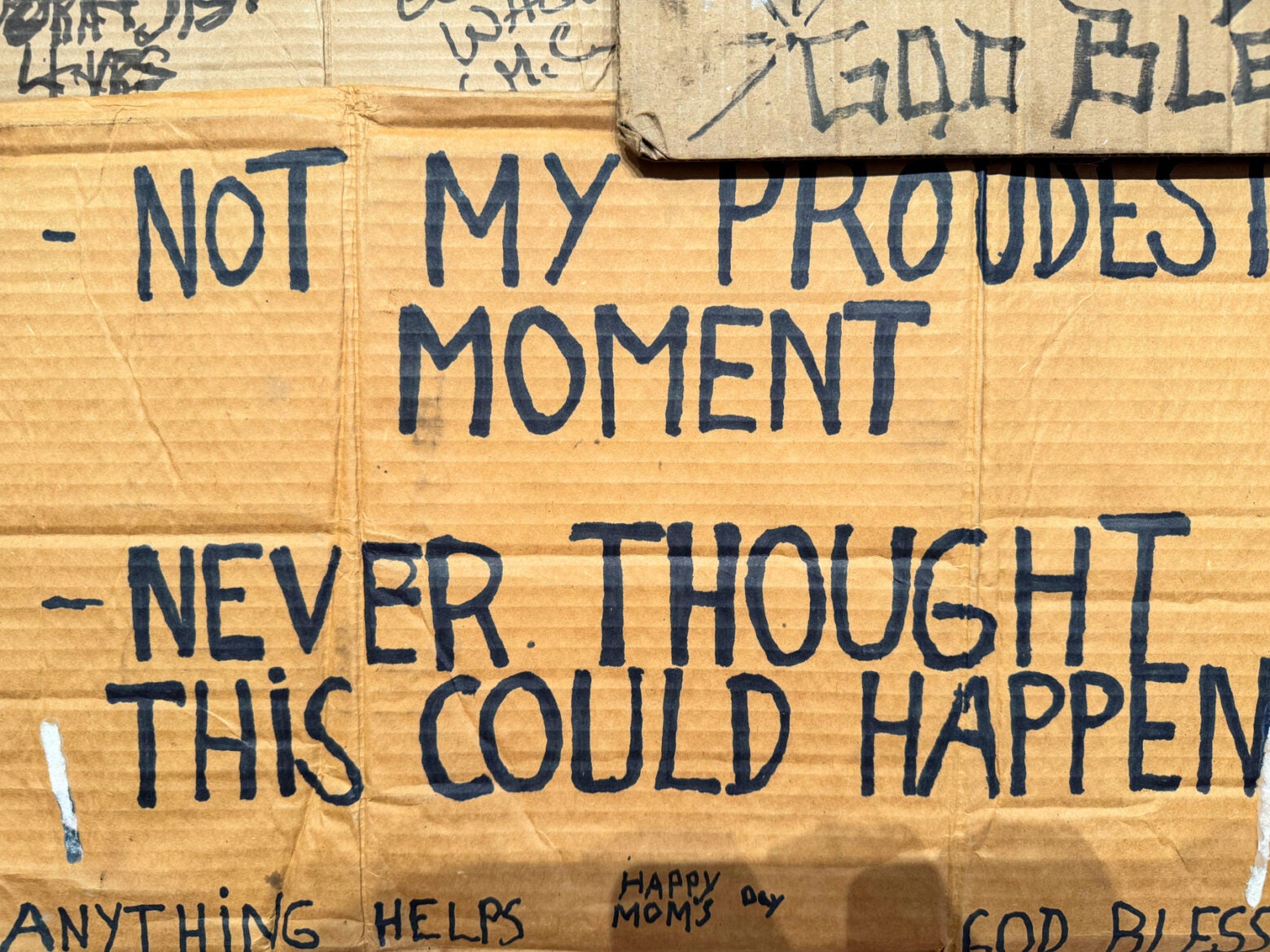

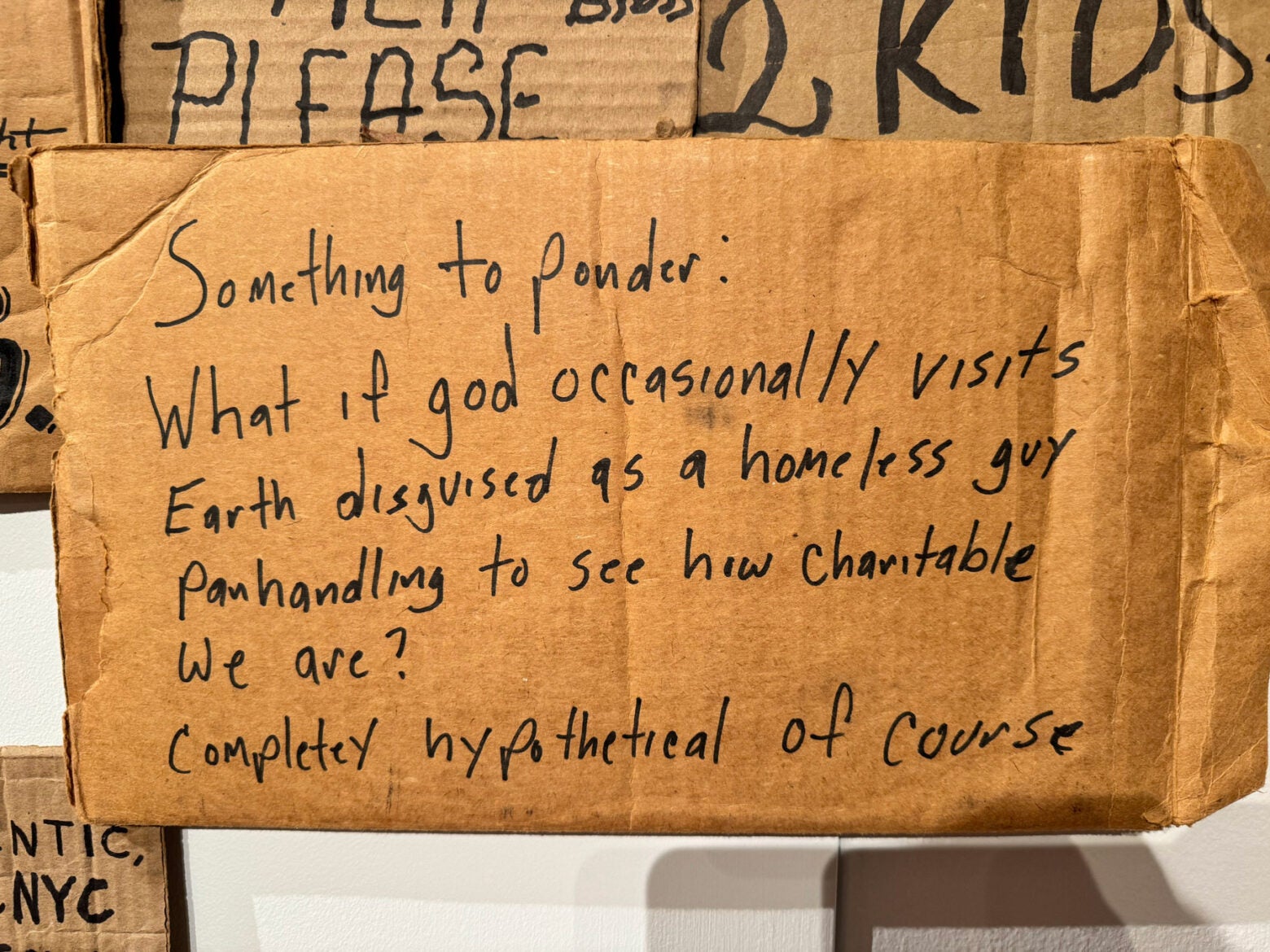

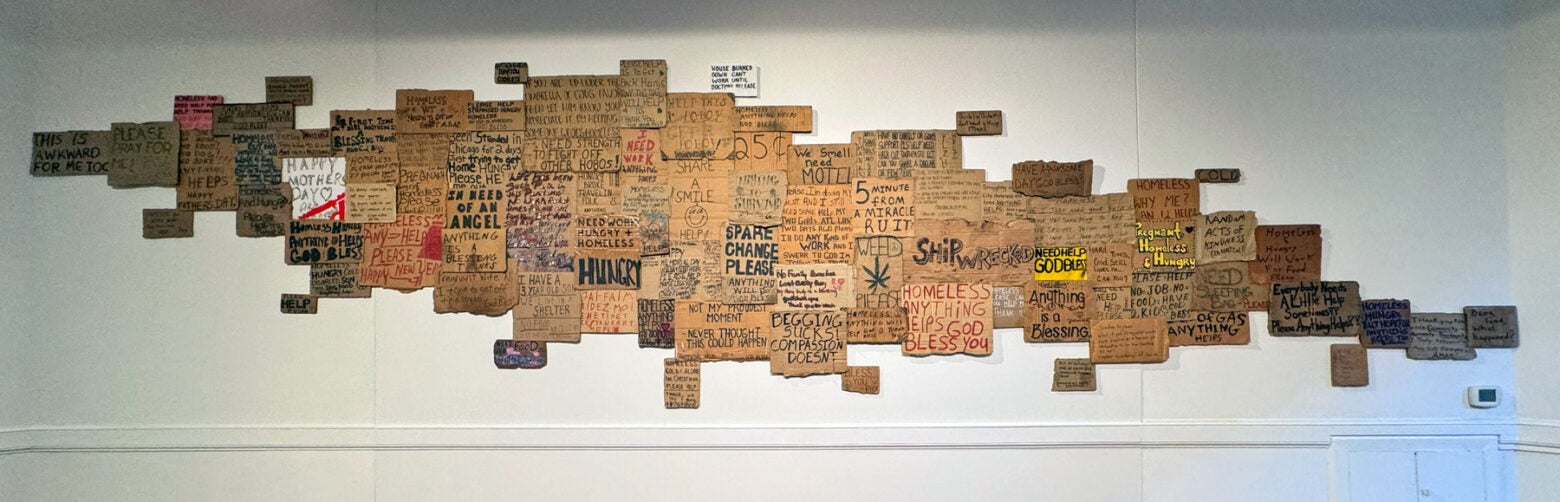

Across from the photographs is an assemblage of cardboard signs, purchased by the artist Willie Baronet during cross-country travels for a project he calls We Are All Homeless. Often wrenching and sometimes wryly comic, they entreat passersby for help. “Begging sucks! Compassion doesn’t,” says one. Another cries out, “Shipwrecked.” Together, they send a clear and powerful message: Stop and look. Take notice.

Four benches arrayed in the center of the gallery encourage reflection, and three bulletin boards allow visitors to post comments on their own attitudes and experiences with homelessness and to respond to those of others. One comment, from a recovering heroin addict from the streets of Philadelphia’s drug-plagued Kensington neighborhood, assures visitors, “There’s hope.”

Unhoused provokes empathy, as it is meant to do. The unhoused are not alien to us; homelessness is a profoundly human affliction, it suggests. But in making its case, the exhibition at times says either too much or too little, belaboring some points and shying away from others.

The introductory label includes a trigger warning about “images that some visitors may find upsetting.” But isn’t part of the point to jar people out of complacency and avoidance? The text also offers some unnecessary moral bludgeoning. “The artists, organizations[,] and public health experts working together on this project regard the topics and people represented in this space with respect and ask that you do the same,” it states. It seems unlikely that the openly disrespectful would tarry here—and heavy-handed to dictate visitors’ responses.

Courtesy of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

Courtesy of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

Cardboard signs collected by artist Willie Baronet for his project "We Are All Homeless," displayed at the Mütter Museum’s exhibition, “Unhoused: Personal Stories & Public Health.”

Courtesy of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

Missing is the discussion of the roots of homelessness, a complicated problem with no single cause and no one-size-fits-all solution. Here the exhibition, in its reluctance to dilute its call to compassion, seems to pull its punches.

Its text rightly notes that “[l]ack of affordable housing, coupled with low-paying jobs, contributes to homelessness.” It adds, “People experiencing homelessness are further impacted by more limited access to doctors, mental health care, and other resources. In addition, unhoused people are at greater risk for mental illness and substance use disorders.”

What this wording fails to grapple with is the extent, however difficult to quantify, that mental illness and substance abuse contribute to the plight of the long-term unhoused. One text label does reveal that an astonishing 76 percent of people entering a federal program, the Collaborative Initiative to Help End Chronic Homelessness, had a mental illness. “It’s a little bit of a chicken-and-egg problem,” says René Najera, director of public health at the College of Physicians, who helped curate the exhibition. Given the sketchiness of the evidence, he says, the museum “didn’t want to stigmatize any further. Ultimately, the message was that people who are unhoused are people. We need to think of them as our neighbors.”

In any case, the exhibition’s statistics on the lack of affordable housing in Philadelphia are striking. At the minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, a full-time employee would earn $1,160 a month before taxes in a city where only six percent of apartments rent for less than $1,000 a month. That would seem to make finding affordable housing almost impossible for low-wage workers. We also learn that homelessness increased nationally by 12 percent from 2022 to 2023, that it affects more than 650,000 people, and that fully half of families with children experiencing homelessness are Black. The show doesn’t delve into the racial dimension of the problem. Along with discrimination, it may reflect the expense of housing in urban centers where many of these families live.

In contrast, the den Bok interviews underline the links between substance abuse, mental illness, and homelessness. Zaks, a luxuriantly bearded older man in Los Angeles, holds an unlit joint and declares that he is “always stoned.” Maria José, a Spanish woman with a soulful visage, talks about depression and a suicide attempt that left a scar on her neck. Jeff is on crystal meth, though it’s not clear whether his drug use is more cause or effect of his homelessness.

While some of the interviewees are almost completely inarticulate, Vaughan, an electrician born and raised in New Zealand, has clear views on homelessness. “It’s mainly a choice because everyone could be off the streets if they really wanted to,” he insists. “I’ve found the worst … the biggest thing on the streets is mental health issues.”

The exhibition nods to Philadelphia nonprofits, including Project HOME and the Sunday LOVE Project, trying to alleviate homelessness. It also quotes a 2021 study on interactions between the unhoused and passersby, “Even a smile helps,” led by Rosemary Frasso, director of the public health program at Thomas Jefferson University and a consultant to the exhibition. The research involved 40 interviews with Philadelphia panhandlers who let the artist Baronet, listed as a study author, buy signs from them. “Human beings aren’t meant to live like this,” said one of the panhandlers. Said another, “You don’t have to give us anything, just let us know that you see us.” The study underscored what it called “the universal need for safety and meaningful human connection.”

Broader, systemic solutions to the problem of homelessness—including more affordable housing and more accessible health care—are obviously necessary. But the first step, Unhoused successfully argues, is for more of us not to avert our gaze.

Unhoused: Personal Stories and Public Health; through August 5;

The Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, 19 S. 22nd St., Philadelphia

Lead image: Courtesy of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

Republish this article

<p>We can’t solve the problem of homelessness if we look away.</p>

<p>Written by Julia M. Klein</p>

<p>This <a rel="canonical" href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/policy-practice/unhoused-exhibit-paints-a-portrait-of-public-health-in-crisis/">article</a> originally appeared in<a href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/">Harvard Public Health magazine</a>. Subscribe to their <a href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/subscribe/">newsletter</a>.</p>

<p class="has-drop-cap">An exhibition on the living might seem an odd fit for a museum best known for its collections of skulls, body parts, and medical oddities. But with <em>Unhoused: Personal Stories and Public Health</em>, the Mütter Museum, run by the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, is both gesturing to the college’s late-18<sup>th</sup>-century origins in fighting epidemics and signaling a possible new direction.</p>

<p>Elsewhere in the museum, a <a href="https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/the-curious-case-of-mrs-ellenbogen/" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">saponified corpse</a> known as “the soap lady,” preserved fetuses, and slides of Albert Einstein’s brain vie for attention. Another exhibition highlights the issues of consent, provenance, representation, and medical racism that have shadowed the Mütter’s past.</p>

<p>In <em>Unhoused, </em>however, the museum’s motto, “Disturbingly Informative,” assumes a different meaning. What may be most disturbing is our failure to pay attention to the public health problem on our doorsteps.</p>

<p>Confined to a single gallery, <em>Unhoused </em>doesn’t purport to offer a definitive account of the complex links between homelessness and public health. Instead, it provides a space to contemplate individual perspectives.</p>

<p>The focal point of the exhibition is two displays of art—both, in effect, collages. Leah den Bok, a Toronto-based photographer, supplies 40 large, exquisitely detailed black-and-white portraits from an ongoing project she titles <em>Humanizing the Homeless.</em></p>

<p>Set against black backgrounds, den Bok’s subjects, ranging from a two-year-old to a man in his 80s, are grimy, occasionally wild-eyed, often visibly sad. They can seem lost, or confrontational. Some face the viewer directly; others look away. A catalog offers quotations and bare-bones background information from interviews conducted by the photographer and her father, Tim den Bok. (It would be better if key quotes also were highlighted via wall labels.) The men and women, from Canada, the United States, India, and elsewhere, talk of family cutoffs<strong>,</strong> drug addiction, mental illness, and the challenges of life on the streets.</p>

<p>Across from the photographs is an assemblage of cardboard signs, purchased by the artist Willie Baronet during cross-country travels for a project he calls <em>We Are All Homeless. </em>Often wrenching and sometimes wryly comic, they entreat passersby for help. “Begging sucks! Compassion doesn’t,” says one. Another cries out, “Shipwrecked.” Together, they send a clear and powerful message: <em>Stop and look. Take notice.</em> </p>

<p>Four benches arrayed in the center of the gallery encourage reflection, and three bulletin boards allow visitors to post comments on their own attitudes and experiences with homelessness and to respond to those of others. One comment, from a recovering heroin addict from the streets of Philadelphia’s drug-plagued Kensington neighborhood, assures visitors, “There’s hope.”</p>

<p><em>Unhoused </em>provokes empathy, as it is meant to do. The unhoused are not alien to us; homelessness is a profoundly human affliction, it suggests. But in making its case, the exhibition at times says either too much or too little, belaboring some points and shying away from others.</p>

<p>The introductory label includes a trigger warning about “images that some visitors may find upsetting.” But isn’t part of the point to jar people out of complacency and avoidance? The text also offers some unnecessary moral bludgeoning. “The artists, organizations[,] and public health experts working together on this project regard the topics and people represented in this space with respect and ask that you do the same,” it states. It seems unlikely that the openly disrespectful would tarry here—and heavy-handed to dictate visitors’ responses.</p>

<p>Missing is the discussion of the roots of homelessness, a complicated problem with no single cause and no one-size-fits-all solution. Here the exhibition, in its reluctance to dilute its call to compassion, seems to pull its punches.</p>

<p>Its text rightly notes that “[l]ack of affordable housing, coupled with low-paying jobs, contributes to homelessness.” It adds, “People experiencing homelessness are further impacted by more limited access to doctors, mental health care, and other resources. In addition, unhoused people are at greater risk for mental illness and substance use disorders.”</p>

<p>What this wording fails to grapple with is the extent, however difficult to quantify, that mental illness and substance abuse contribute to the plight of the long-term unhoused. One text label does reveal that an astonishing 76 percent of people entering a federal program, the Collaborative Initiative to Help End Chronic Homelessness, had a mental illness. “It’s a little bit of a chicken-and-egg problem,” says René Najera, director of public health at the College of Physicians, who helped curate the exhibition. Given the sketchiness of the evidence, he says, the museum “didn’t want to stigmatize any further. Ultimately, the message was that people who are unhoused are people. We need to think of them as our neighbors.”</p>

<p>In any case, the exhibition’s statistics on the lack of affordable housing in Philadelphia are striking. At the minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, a full-time employee would earn $1,160 a month before taxes in a city where only six percent of apartments rent for less than $1,000 a month. That would seem to make finding affordable housing almost impossible for low-wage workers. We also learn that homelessness increased nationally by 12 percent from 2022 to 2023, that it affects more than 650,000 people, and that fully half of families with children experiencing homelessness are Black. The show doesn’t delve into the racial dimension of the problem. Along with discrimination, it may reflect the expense of housing in urban centers where many of these families live.</p>

<p>In contrast, the den Bok interviews underline the links between substance abuse, mental illness, and homelessness. Zaks, a luxuriantly bearded older man in Los Angeles, holds an unlit joint and declares that he is “always stoned.” Maria José, a Spanish woman with a soulful visage, talks about depression and a suicide attempt that left a scar on her neck. Jeff is on crystal meth, though it’s not clear whether his drug use is more cause or effect of his homelessness.</p>

<p>While some of the interviewees are almost completely inarticulate, Vaughan, an electrician born and raised in New Zealand, has clear views on homelessness. “It’s mainly a choice because everyone could be off the streets if they really wanted to,” he insists. “I’ve found the worst … the biggest thing on the streets is mental health issues.”</p>

<p>The exhibition nods to Philadelphia nonprofits, including Project HOME and the Sunday LOVE Project, trying to alleviate homelessness. It also quotes a 2021 study on interactions between the unhoused and passersby, “<a href="https://journals.sagepub.com/eprint/4JUM9IYIC3KPCIMIWXAR/full" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">Even a smile helps</a>,” led by Rosemary Frasso, director of the public health program at Thomas Jefferson University and a consultant to the exhibition. The research involved 40 interviews with Philadelphia panhandlers who let the artist Baronet, listed as a study author, buy signs from them. “Human beings aren’t meant to live like this,” said one of the panhandlers. Said another, “You don’t have to give us anything, just let us know that you see us.” The study underscored what it called “the universal need for safety and meaningful human connection.”</p>

<p class=" t-has-endmark t-has-endmark">Broader, systemic solutions to the problem of homelessness—including more affordable housing and more accessible health care—are obviously necessary. But the first step, <em>Unhoused </em>successfully argues, is for more of us not to avert our gaze.</p>

<p class="is-style-t-caption"><em><a href="https://muttermuseum.org/on-view/unhoused-personal-stories-and-public-health" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">Unhoused: Personal Stories and Public Health</a></em>; through August 5;<br>The Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, 19 S. 22<sup>nd</sup> St., Philadelphia</p>

<script async src="https://www.googletagmanager.com/gtag/js?id=G-S1L5BS4DJN"></script>

<script>

window.dataLayer = window.dataLayer || [];

if (typeof gtag !== "function") {function gtag(){dataLayer.push(arguments);}}

gtag('js', new Date());

gtag('config', 'G-S1L5BS4DJN');

</script>

Republishing guidelines

We’re happy to know you’re interested in republishing one of our stories. Please follow the guidelines below, adapted from other sites, primarily ProPublica’s Steal Our Stories guidelines (we didn’t steal all of its republishing guidelines, but we stole a lot of them). We also borrowed from Undark and KFF Health News.

Timeframe: Most stories and opinion pieces on our site can be republished within 90 days of posting. An article is available for republishing if our “Republish” button appears next to the story. We follow the Creative Commons noncommercial no-derivatives license.

When republishing a Harvard Public Health story, please follow these rules and use the required acknowledgments:

- Do not edit our stories, except to reflect changes in time (for instance, “last week” may replace “yesterday”), make style updates (we use serial commas; you may choose not to), and location (we spell out state names; you may choose not to).

- Include the author’s byline.

- Include text at the top of the story that says, “This article was originally published by Harvard Public Health. You must link the words “Harvard Public Health” to the story’s original/canonical URL.

- You must preserve the links in our stories, including our newsletter sign-up language and link.

- You must use our analytics tag: a single pixel and a snippet of HTML code that allows us to monitor our story’s traffic on your site. If you utilize our “Republish” link, the code will be automatically appended at the end of the article. It occupies minimal space and will be enclosed within a standard <script> tag.

- You must set the canonical link to the original Harvard Public Health URL or otherwise ensure that canonical tags are properly implemented to indicate that HPH is the original source of the content. For more information about canonical metadata, click here.

Packaging: Feel free to use our headline and deck or to craft your own headlines, subheads, and other material.

Art: You may republish editorial cartoons and photographs on stories with the “Republish” button. For illustrations or articles without the “Republish” button, please reach out to republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.

Exceptions: Stories that do not include a Republish button are either exclusive to us or governed by another collaborative agreement. Please reach out directly to the author, photographer, illustrator, or other named contributor for permission to reprint work that does not include our Republish button. Please do the same for stories published more than 90 days previously. If you have any questions, contact us at republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.

Translations: If you would like to translate our story into another language, please contact us first at republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.

Ads: It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads, but not ads specifically sold against our stories. You can’t state or imply that donations to your organization support Harvard Public Health.

Responsibilities and restrictions: You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third-party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. Harvard Public Health recognizes that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties aggregate or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

You may not republish our material wholesale or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You may not use our work to populate a website designed to improve rankings on search engines or solely to gain revenue from network-based advertisements.

Any website on which our stories appear must include a prominent and effective way to contact the editorial team at the publication.

Social media: If your publication shares republished stories on social media, we welcome a tag. We are @PublicHealthMag on X, Threads, and Instagram, and Harvard Public Health magazine on Facebook and LinkedIn.

Questions: If you have other questions, email us at republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.