Feature

Families in states with bans on trans care are finding hope across state lines

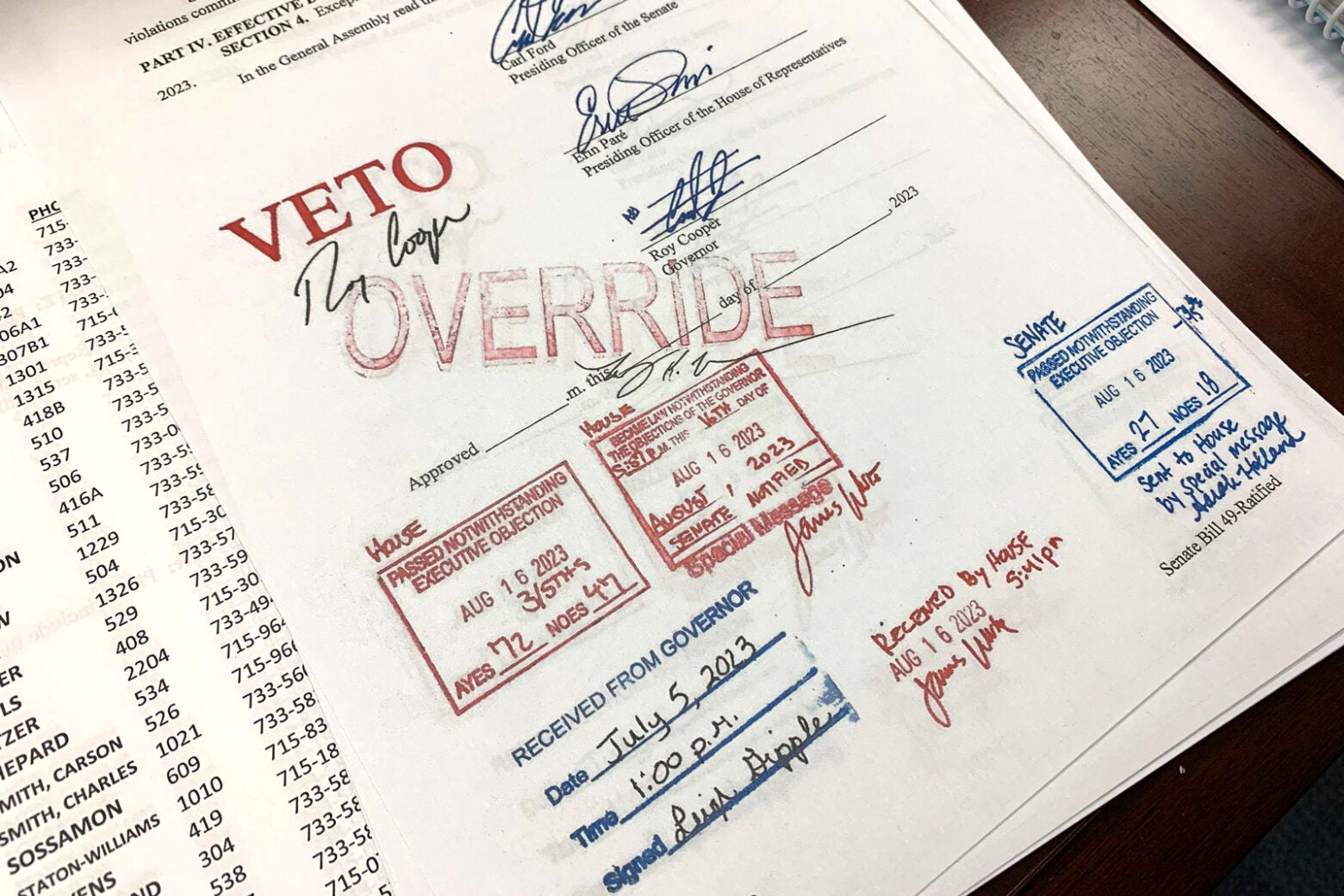

North Carolina’s House of Representatives debated for only four minutes before casting a final vote to restrict medical treatment for transgender youth. The Senate followed some two hours later, on the evening of August 16, 2023.

Ten miles outside Raleigh, where the legislature was meeting, a 15-year-old theater kid named Leo was preparing for a sleepover with his best friend. Neither he nor his parents were aware of the vote, or of how it would alter the course of his medical care. His endocrinologist, Deanna Adkins, learned about the vote immediately, and knew it would change the way she and her team practiced medicine. They had a new game plan ready, and it was time to roll it out.

Adkins co-founded and directs the Duke Child and Adolescent Gender Care Clinic, one of the oldest facilities of its type in the South. She had been bracing all summer for the legislature to outlaw much of her work, as part of a wave of anti-transgender rights legislation sweeping the nation. In July, Governor Roy Cooper had vetoed House Bill 808, the legislature’s attempt to bar physicians from prescribing hormonal therapies to minors seeking gender transition. In his veto message, he declared, “A doctor’s office is no place for politicians.” It was clear, however, that the lawmakers in the state’s Republican supermajority disagreed and would move to override his veto.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

The bill exempted some patients who were already in treatment. Knowing this, Adkins and her clinic staff had gone into overdrive. They lengthened their hours. They contacted waiting families and offered them earlier consultations. They referred some of their other patients—Adkins also treats diabetes and other conditions—to different endocrinologists, who stretched their own clinical capacities to accommodate the demand. They asked other therapists to assist with psychosocial assessments. The goal was to accelerate schedules without rushing decisions or compromising safety protocols.

Deanna Adkins, director of the Duke Child and Adolescent Gender Care Clinic, has had to become an advocate for patients.

“We were all exhausted,” says Kristen Russell, the clinical social worker in Adkins’s clinic. “We knew that we only had a certain amount of time, so it was just all hands on deck.”

Some of the parents and teens arrived frightened that long-awaited care was in jeopardy, says Dane Whicker, a Duke University clinical health psychologist who helped with the assessments. The professionals, meanwhile, stayed on task. “You’re sort of in the zone,” he says. “But at the same time, it’s this weird experience.” After all, virtually every major medical association in the United States has opposed bans on minors’ access to gender-affirming care, yet 25 states have passed laws limiting such access. Under the North Carolina bill, any doctor who provided such care would lose their medical license, and could also be sued by former pediatric patients for decades afterward. “What are we doing here?” Whicker recalls thinking. “Especially after so many years, where we’re building the evidence base, we’re growing as a field, the research is there. And then all of a sudden, it’s like going back into the Dark Ages.”

Adkins’s summertime push to work through her backlog before a potential veto override led her to start treatment for about 25 new patients. Leo and his family thought he would be one of them.

Leo near his home in North Carolina. He says it's been a relief to begin the transition process.

Twelve days before the override vote, Leo and his parents had arrived at Adkins’s clinic in Durham. “I was feeling really hopeful and excited,” he says. He underwent a medical exam and bloodwork to measure his hormone levels. The family met with Adkins and Russell, who detailed the treatment options and answered their questions. “I never felt like they were pushing one way or the other,” says Leo’s father. “That made me really comfortable.”

Russell followed up, four days later, with a two-hour psychosocial assessment, which confirmed that Leo met the diagnostic criteria for gender dysphoria, the persistent and clinically significant distress that some transgender people experience. “It’s not just that they’re uncomfortable in their body,” she says, “but it’s actually impairing their functioning.”

Even though Leo sang and danced his way through childhood—“always living in a Disney musical,” says his mother—he never felt at home in his body. When he was in first grade, Leo wrote a story about a skateboarding penguin, and then panicked when he heard a recording of himself reading it aloud. He had imagined his pitch was deeper; he didn’t want to sound like a girl. He wanted to sound like Zuko, the fire-bending prince from Avatar. He came to hate his voice, and to hate being seen as cute. “I didn’t know what to say or do to make it better,” his mother says. (Harvard Public Health is not naming the parents or using Leo’s last name to help shield them from harassment.)

Leo and his parents in their kitchen soon after his treatments began.

It took seven more anxious years, and many family conversations, before Leo figured out he was transgender. He cut his hair short, adopted male pronouns, and legally changed his name. He celebrated small victories, like when a lifeguard at the pool called him “buddy.” But he was also entering female adolescence and would soon have a body most would perceive as female. He wanted to start taking testosterone to align his body with his gender identity.

His parents were open-minded, but also trying to make sense of what they were hearing from their only child. Was he really trans? If so, were hormones the best course? There were so many conflicting opinions. “It was scary,” his mother says. “We were alone. We had nobody to talk to.” Leo’s mother had found Adkins’s clinic online, and knew the Duke University Health System’s reputation; the family had had other good experiences with Duke specialists. In late 2022, when Leo was 14, his parents reached out to the clinic. House Bill 808 would be introduced in April 2023.

The bill was not yet law when Russell performed the psychosocial assessment on August 8, or when Leo met with a physical therapist three days later. When the legislation was finally ratified, on August 16, the exemption covered patients who had begun treatment before August 1. It took protracted legal consultations for Adkins and her team to figure out the status of patients who, like Leo, fell into that 16-day hole.

One of several bills on LGBTQ+ issues that were vetoed by North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper and overridden by the state's General Assembly on August 16, 2023. One of the bills banned gender-affirming care for minors.

Hannah Schoenbaum / AP Photo

The limbo felt interminable to Leo. “I had been waiting and waiting and waiting and then waiting more,” Leo says. “I was sick of not even being at the starting point yet.”

That fall, Leo’s parents joined a support group at the clinic, an experience that validated his mother’s conclusion that testosterone was critical to his mental health. In a national survey of 28,000 LGBTQ young people, published in 2023 by the nonprofit Trevor Project, half the transgender and nonbinary respondents had seriously considered suicide within the previous year. A study of youth treated at Seattle Children’s Gender Clinic revealed that access to hormonal therapies reduced the odds of self-harm or suicidal thoughts by 73 percent. The study, published in 2022, also showed a 60 percent lower chance of depression for those receiving puberty blockers or gender-affirming hormones.

“I would rather have an alive kid on testosterone,” says Leo’s mom, “than a dead kid that’s not on testosterone.”

There was one more safety hurdle before Leo could start taking testosterone: a letter of support from his private therapist. That letter arrived in late November 2023. But the deadline to begin hormonal therapy in North Carolina had passed. If Leo, his parents, and the clinic team still believed he needed testosterone before his 18th birthday, they’d have to find another way.

Adkins is not an activist by nature. “I had a huge fear of the legal system,” she says. “One of the reasons I chose this specialty is that there’s no risky anything. It’s pretty straightforward.” She was drawn to endocrinology because it felt like engineering, her initial undergraduate major. She began practicing at Duke in 2004 and did not intend to treat trans kids until an out-of-town colleague asked her in 2014 to see a patient who lived in North Carolina and needed a hormonal transition.

Since then, Adkins has seen about 700 patients with gender dysphoria. And in the current political climate, she understands that advocacy is part of her job. When North Carolina first tried to restrict pediatric gender-affirming care in 2021 with legislation similar to House Bill 808, she spoke out publicly against the effort.

That same year, Arkansas became the first state to ban such care. Adkins signed on as a medical expert in the lawsuit seeking to overturn the measure. On the witness stand in 2022, she laid out the professional consensus in the United States: Gender dysphoria, untreated, puts patients at risk for depression, self-harm, and suicidality. Some teens, she testified, can’t afford to delay treatment until adulthood: “I lost a patient to suicide because they did not make it to their second visit.”

Adkins told the Arkansas court that each of her patients goes through a robust assessment that covers their medical history, family dynamics, and educational issues, along with mental-health concerns like eating disorders, depression, and trauma. Then her team works with the family to develop an individualized care plan. That plan occasionally means pausing puberty until a younger patient can clarify their gender identity, so they don’t have to worry about unwanted physical changes like breast development or the deepening of their voice. More often, though not always, it means prescribing gender-affirming hormones for older adolescents. She explained to the court, “If you align the body with the identity . . . it can decrease their depression, their anxiety, their dysphoria.”

A federal judge cited Adkins’ testimony when he blocked the Arkansas law in June 2023. The case is now under appeal. (In total, the courts have fully or partly blocked similar laws in four states; the other 21 are in effect.) This summer, the U.S. Supreme Court announced it would review the legality of state bans on gender-affirming care for minors, taking up a case from Tennessee. The justices are likely to hear arguments before the end of the year.

The Arkansas ruling came as North Carolina’s legislature was considering House Bill 808, which banned the prescription of both puberty blockers and gender-affirming hormones for minors. It also outlawed pediatric surgery related to gender transition like chest reconstruction, which minors rarely receive and Adkins’s clinic doesn’t offer.

Adkins had hoped the Arkansas ruling would deter her own state’s legislators, but the bill kept barreling forward, and the debate in North Carolina grew particularly contentious: One group made repeated false claims that Duke was transitioning two-year-olds.

One sponsor, Republican State Representative Ken Fontenot, compared gender-affirming care to 20th-century experiments like the Tuskegee Study, in which 399 Black men infected with syphilis went untreated for 40 years. “We as a nation have been at the forefront of medical blunders time and time again, and this is no different,” he said during a floor debate.

Adkins didn’t respond publicly; she says she no longer felt safe visiting the legislature. Boston Children’s Hospital, home of the nation’s first pediatric gender clinic, had received a series of bomb threats, and its doctors were being menaced online. In North Carolina, anti-trans activists had focused their attention on Adkins and Whicker, the psychologist. “There were a lot of death threats,” says Whicker. “You can only see images of yourself going through a wood chipper, á la Fargo, so many times.”

In the clinic, Adkins began to exercise more caution. “We have heard, within our groups, that they’re sending in patients who aren’t really patients to try and record us saying something that looks bad,” she says. In the past, Adkins trusted every patient at their word, within reason. Now, she says, “our little antennae are up” for odd behaviors that might signal an infiltrator.

As House Bill 808 headed toward ratification, Adkins understood that accelerating her schedule would not help everyone. One of her patients would eventually challenge the new law in federal court, but that lawsuit is pending. Those who missed the cutoff needed an immediate, creative solution—an interstate solution. That was the course Leo and his family would have to follow.

Transgender North Carolinians and their supporters in the North Carolina House in May 2023, demanding to speak to a bill banning gender-affirming care for minors. Public comments were not allowed.

Hannah Schoenbaum / AP photo

House Bill 808, it turned out, doesn’t prohibit all care for trans kids. It doesn’t ban intake exams or services like voice therapy, physical therapy, counseling, and pastoral care. Physicians are still allowed to communicate about patient care with their peers outside North Carolina.

So Adkins looked north to Virginia, where pediatric gender-affirming care remains legal. She and the clinic’s fellow talked with colleagues at three Virginia hospitals and developed a hybrid model that would minimize travel. Patients would first come to Duke, where clinic personnel would assess their readiness, lay out the options, and direct them to locally available services like voice therapy. Then the information would be sent to a Virginia physician, who would verify the patient’s eligibility. The family would cross the state line for an appointment with the prescribing doctor and would pick up the medication at a Virginia pharmacy. Duke would do ongoing monitoring.

About 18 of Adkins’s patients, including Leo, now use this interstate solution. One Virginia physician (not Leo’s) told me that the system is working reasonably well. “We’re very lucky with North Carolina,” she says. “[Patients] have already met with Dr. Adkins . . . and it’s very clear that the family has gotten some education, and then we can pick up where they left off. So that is very nice.”

But only a limited number of Virginia doctors do this work, she says, and they’re overwhelmed by medical refugees from nearby states. They also fear that collaborating with doctors in those states will attract hostile attention, particularly because Virginia does not have a shield law protecting transgender health care.

“There’s so [much] behind-the-scenes scrutiny of our logistical process to make sure that we’re protecting ourselves,” she says. “All of us are constantly worried: Is my medical license going to be at stake? Is our institution protected? There’s just this constant concern that we’re going to be attacked.” Because of that concern, Harvard Public Health agreed not to name her or the institution.

That concern has a realistic basis. As a result of the legislative wave, almost 40 percent of the nation’s transgender youth—1.4 percent of 13- to 17-year-olds identify as trans, though not all of them pursue medical transition—live in states that restrict access, according to KFF. Some clinics, like Vanderbilt University’s in Nashville, have shut down entirely. Doctors at Washington University in St. Louis stopped prescribing hormones and puberty blockers to pediatric patients, even those exempt from the ban, saying that Missouri’s law exposed them to “untenable” legal liability. Texas’s only clinic, at Children’s Medical Center in Dallas, closed under pressure from the governor even before the state passed a ban.

The resulting crisis has triggered a response that extends beyond any one hospital system. A nationwide network of professionals and nonprofits now helps trans youth and their families navigate the patchwork system. One key player is the Asheville, North Carolina-based Campaign for Southern Equality, which in 2023 launched an emergency project for families whose states have outlawed gender-affirming care.

As the access map began to shrink, the Campaign built a referral network of providers in safe states who offer care to patients living in restricted ones. Now, when parents reach out, navigators help them think through their options and offer them $500 renewable grants for travel and, in some situations, clinical costs. Since March 2023, the Campaign has distributed more than $500,000 in such grants.

Depending on where a patient lives, traveling to a safe state might entail more than crossing a border. If you live in Alabama, for example, your closest option might be Illinois. For some of those patients, the Campaign partners with Elevated Access, a nonprofit that uses volunteer pilots to fly families to their appointments in small aircraft. (Elevated Access does this for abortion care, too.)

“Getting them there is only part of it,” says Allison Scott, the Campaign’s director of impact and innovation. “How are we going to make sure that they can actually afford it?” At a few clinics, the Campaign has set up care funds to help defray the cost of treatment.

In North Carolina, House Bill 808 complicates payment for patients covered by the exemption because it prohibits the use of state funds for their treatment. Puberty blockers, for example, can cost tens of thousands of dollars, putting them out of reach for families enrolled in Medicaid. At Duke, the hospital absorbed the cost of some patients’ care, deeming it lifesaving. In addition, Adkins has switched some hormone users to less expensive delivery systems, like estrogen pills instead of injections.

Overall, though, Scott says trans children and their families are “getting pummeled” by the bans. And the ripple effects extend to states where the care remains legal. Wait times are growing longer. Providers have seen escalating malpractice premiums and even insurance-coverage denials. Transportation logistics have grown trickier as restrictions spread.

Scott takes comfort in the response from health professionals in safe states.

“We used to have to hunt these clinics down,” she says. “We are getting more providers now, throughout the country, who are reaching out to us, going, ‘Hey, we have capacity. What can we do to help?’ There’s a huge joy component in this because we’re seeing people stepping up to the challenge. They are not going to let these families and these kids have to stand in this alone.”

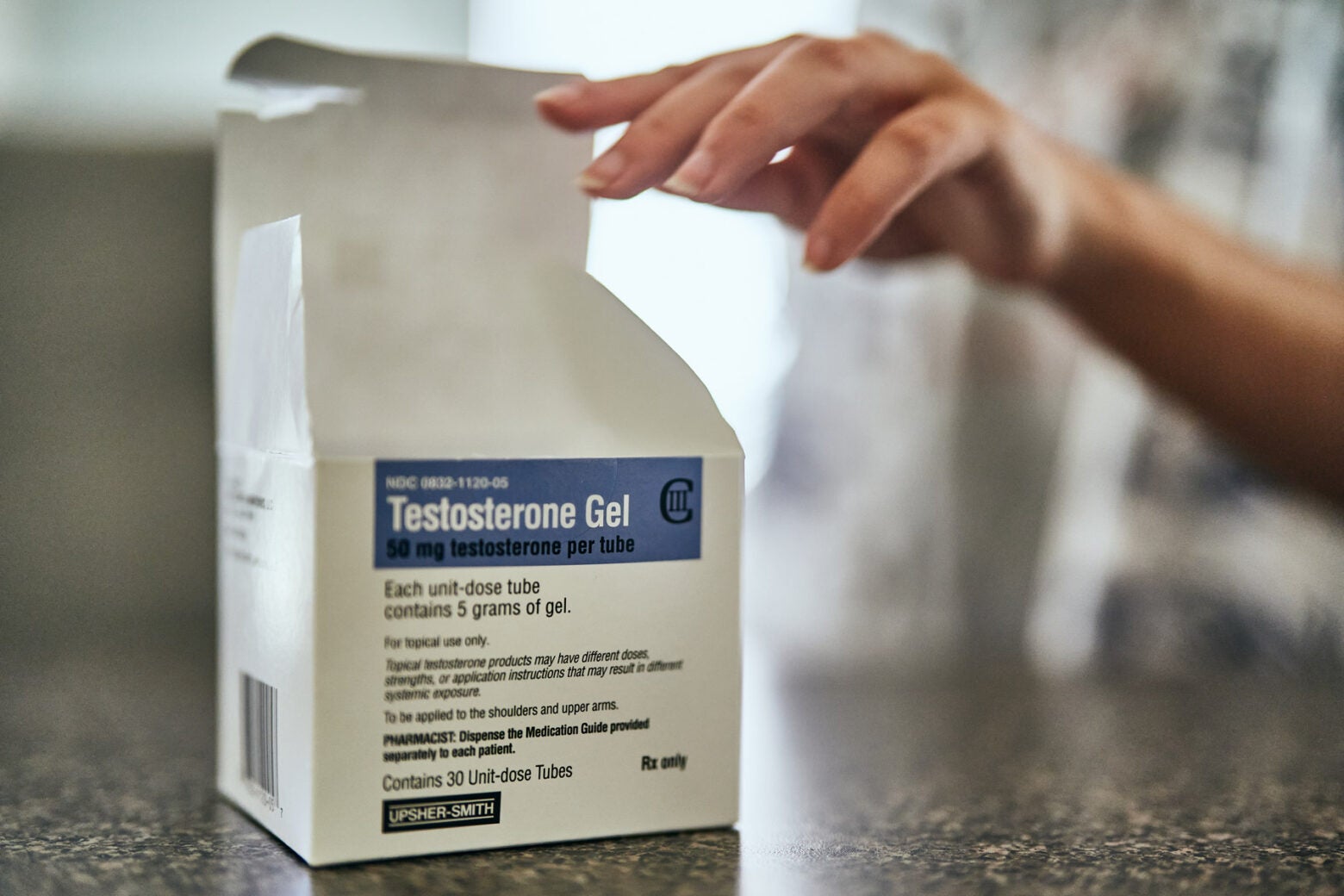

Leo, now 16, and his mother drove four hours to their first appointment with a Virginia endocrinologist in January 2024. They came home with 30 small tubes of testosterone gel and then repeated the process in April. One of those $500 grants from the Campaign for Southern Equality helped pay for their travel.

Leo now has access to hormone treatments.

Leo demonstrating how he applies the testosterone.

He has not noticed any physical changes yet, but just beginning the transition gives Leo reassurance. “When things are stressful for me, it helps just knowing at least I’m starting it already. No matter what, most of those problems are going to be going away soon,” he says. “I’ve just got to be patient.”

His parents view him as less anxious. “Prior to the testosterone, he was hyper-fixated on the frustration and the injustice,” says his mother. But since January, “he’s just more at peace. He doesn’t seem as concerned with how he presents: If he gets misgendered, he knows it’s temporary.” Leo today feels confident enough to wear his curly hair long again. He’s even shed his aversion to the color pink. “He’s more comfortable leaning into all sides of himself,” his mother says.

Leo is fortunate compared to many trans teens. His parents have professional jobs, and his mother can take time off for overnight medical trips. They have been unfailingly supportive, as have other adults in Leo’s life. Plus, he has only one state line to cross. “It sucks that we have to do it at all, because it’s a big hassle,” he says. “But at the very least . . . we’re not in a deep, deep South area.”

On both Virginia trips, snafus at the pharmacy delayed their return home. “It’s anxiety-ridden, because I know I have to leave there with testosterone,” his mother says. “We’ve done all that work: taking off school and paying all that money for gas and the hotel, and me taking off work. And then to be, at that last moment, in that pharmacy where we’re so close to being done and going home. Both times have been extremely stressful. And it’s like, well, what do we do next?”

These out-of-state trips, she understands, are part of raising a trans teen in 2024. “The truth is,” she says, “I would travel wherever I needed to.”

Lead image: Leo in the woods near his home in North Carolina in June.