Opinion

Public health gets a much-needed hug

Remember when people loved public health? Neither does anyone else. The Invisible Shield, a new four-part documentary directed by Jason Kliot and Taimi Arvidson, tries to remind us why we should be grateful for the system we have in the United States. The filmmakers create an intimate portrait and include some familiar stories told wonderfully. At the same time, people who know the field well may find themselves speeding up their streams (I watched with an epidemiologist I know who got bored in places).

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Episode one, “The Old Playbook,” examines the time when vaccines and public health interventions were yet to come. “Imagine a world where no vaccines existed, where a third of your children died before reaching adulthood. This was the reality of all human life until just about a hundred years ago,” Steven Johnson, author of Extra Life and The Ghost Map, tells viewers. Then came the rise of public health, the “invisible shield” that protects all humans. Johnson sheds light on this metaphor not even three minutes into the start of the series. Joshua Sharfstein, a physician and a professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, solidifies it: “Public health saved your life today, and you didn’t even know it.”

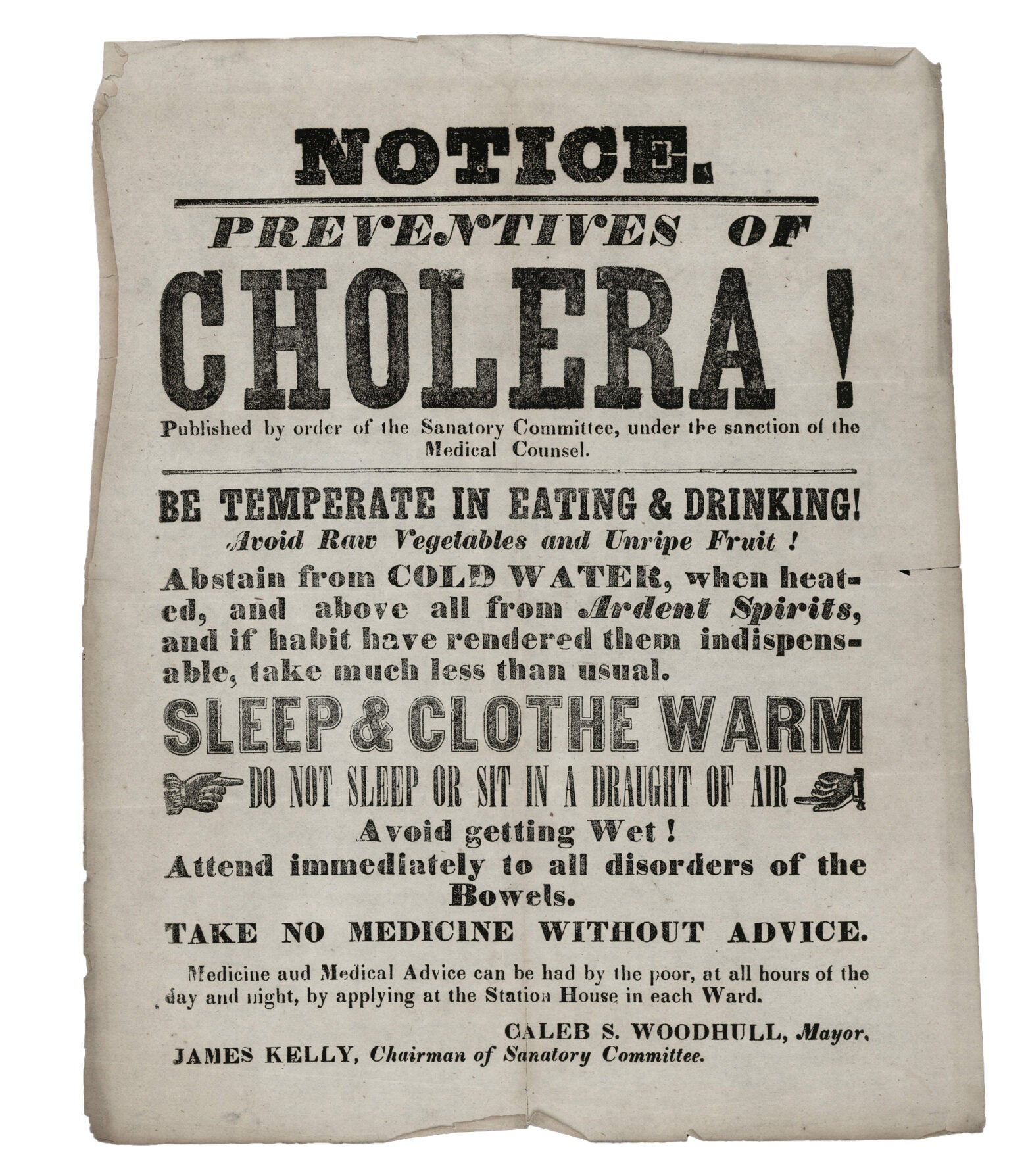

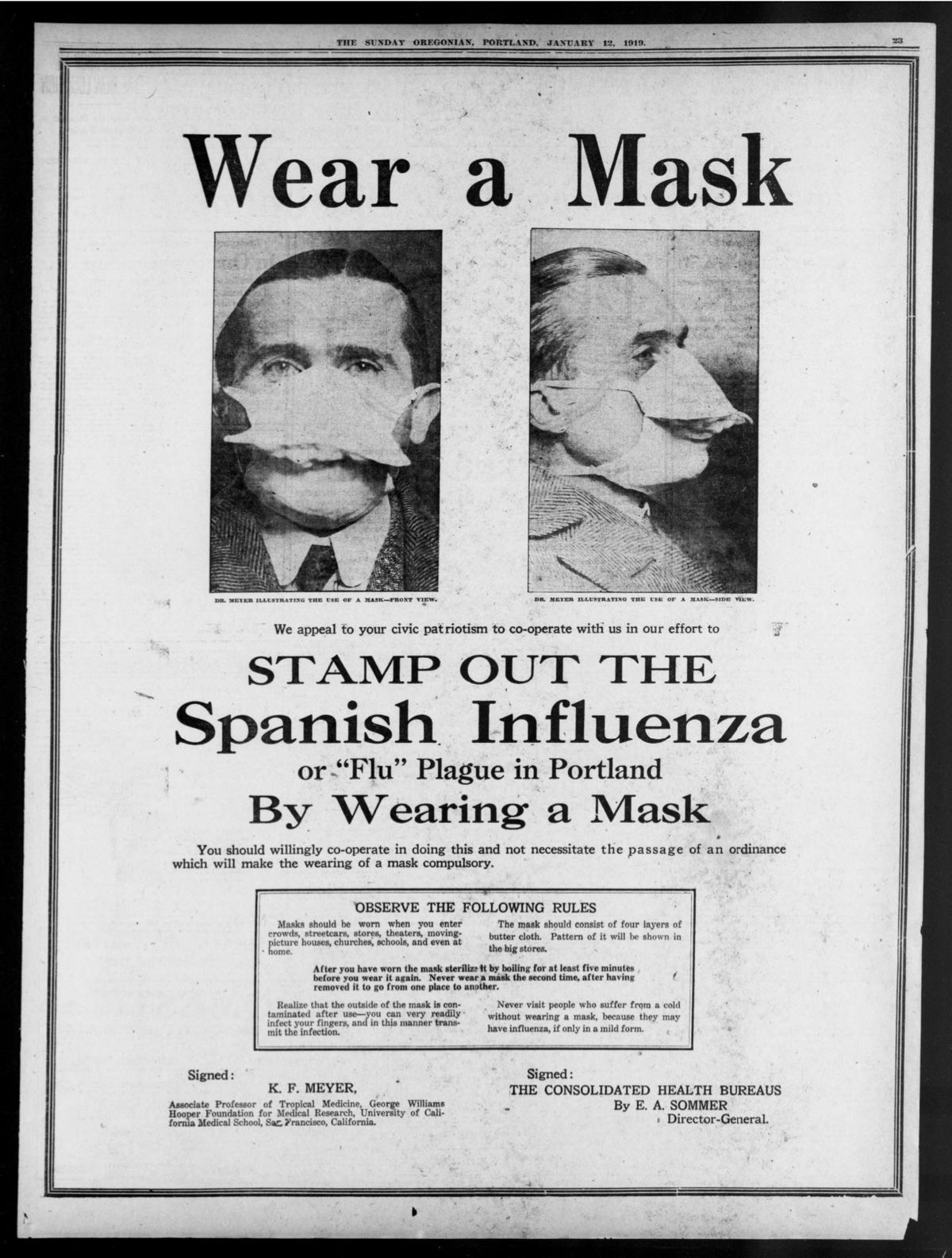

We are taken back to a time when people did know this, when they got to see smallpox, cholera, and other harrowing diseases tamed or eliminated. But we also see what happened during COVID-19, when the system seemed to fail so many of us. These stories are woven through each episode and serve as a backdrop for a candid discussion of the major issues facing the public health system today. The second episode, “Follow the Data,” highlights (you probably know what’s coming) John Snow’s efforts to stop the spread of cholera in London’s Soho district during the 19th century. This story is like something out of public health Genesis: “And John Snow looked at the data, and he saw that it was good, and he called it ‘epidemiology.’” The documentary gives it a terrific refresh—it illuminates this history with an exceptionally detailed rendering of the black-and-white map Snow used to track cholera-related deaths in the town. (Skip to the 18-minute mark to check out the cool animated bird’s-eye view of his famous map.) The map enlivens what is, at heart, a discussion of the advent of data collection as a core tenet of the field. The last quarter of the episode delves into race and ethnicity reporting issues, making for a nice segue into the third episode, “Inoculation & Inequity.”

A notice from the New York Board of Health, 1849

National Library of Medicine / The Invisible Shield

A public health poster from 1919

Sunday Oregonian / The Invisible Shield

In episode three, we are reminded of the history of public health injustices, such as (again, you know what’s coming) the Tuskegee syphilis study and the resulting mistrust between health care workers and people of color, particularly African Americans. The roots of distrust go much further back, as we hear from Lauren Powell, president and CEO of The Equitist: “We have plenty of evidence to show us that there is differential treatment between Black patients and white patients, that physicians often under-prescribe medication for Black patients and falsely think that we have thicker skin than white patients and therefore can tolerate more pain, which is directly connected to slavery.” Beautifully and succinctly said.

As a Black woman, I commend the directors for devoting an entire episode to how systemic racism has birthed numerous health care inequities for Black and brown folks. It’s a gravely significant issue; the filmmakers addressed it both boldly and sensitively.

Of course, we’re all aware of how COVID-19 helped push inequities to the forefront of the world’s collective consciousness. The pandemic also revealed some trials and errors of public health professionals and scientists—mistakes that, for many people, overshadow how quickly the scientists created vaccines and stopped the spread of the coronavirus. The question now is: Can public health do better?

The final episode, “The New Playbook,” seeks to answer that question—but falls a bit flat in its efforts to do so. We are told we should do things like hire chief health strategists, create better data analytics, alleviate stress for public health workers, and invest in more resources for the field. What we don’t hear enough about is how. Do we, for instance, give them mental health days? What would it take to offer those workers free mental health services? How can we get people to put community interest ahead of individual interest? How can we ensure that people don’t just think “the pandemic is over” and forget what a mess things were four years ago? In a series that sometimes seemed to go on too long, this episode left me wanting more.

The series features many of the field’s brightest and most influential minds, which allows viewers to appreciate the breadth and scope of the field. But there are almost two dozen of them spread across a little over three-and-a-half hours of footage. It’s like the Marvel Universe invaded a public health documentary, so you are constantly trying to remember who used what superpower back in issue 74.

Still, Invisible Shield is worth watching, if only because it tells some good stories, a skill desperately lacking in public health. Ideas are for the most part clearly articulated, and there are captivating graphics in each episode.

Top image, TV tile art: The Invisible Shield

Republish this article

<p><i>The Invisible Shield</i> might be the morale booster the field needs.</p>

<p>Written by Ayana Underwood</p>

<p>This <a rel="canonical" href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/policy-practice/history-of-public-health-is-subject-of-new-pbs-documentary/">article</a> originally appeared in<a href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/">Harvard Public Health magazine</a>. Subscribe to their <a href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/subscribe/">newsletter</a>.</p>

<p class="has-drop-cap">Remember when people loved public health? Neither does anyone else. <em><a href="https://www.pbs.org/show/the-invisible-shield/">The Invisible Shield</a>,</em> a new four-part documentary directed by Jason Kliot and Taimi Arvidson, tries to remind us why we should be grateful for the system we have in the United States. The filmmakers create an intimate portrait and include some familiar stories told wonderfully. At the same time, people who know the field well may find themselves speeding up their streams (I watched with an epidemiologist I know who got bored in places).</p>

<p>Episode one, “The Old Playbook,” examines the time when vaccines and public health interventions were yet to come. “Imagine a world where no vaccines existed, where a third of your children died before reaching adulthood. This was the reality of all human life until just about a hundred years ago,” Steven Johnson, author of <em>Extra Life </em>and<em> The Ghost Map</em>, tells viewers. Then came the rise of public health, the “invisible shield” that protects all humans. Johnson sheds light on this metaphor not even three minutes into the start of the series. Joshua Sharfstein, a physician and a professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, solidifies it: “Public health saved your life today, and you didn’t even know it.”</p>

<p>We are taken back to a time when people did know this, when they got to see smallpox, cholera, and other harrowing diseases tamed or eliminated. But we also see what happened during COVID-19, when the <a href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/reviews/new-sandro-galea-public-health-book-looks-back-at-pandemic/" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">system seemed to fail</a> so many of us. These stories are woven through each episode and serve as a backdrop for a candid discussion of the major issues facing the public health system today. The second episode, “Follow the Data,” highlights (you probably know what’s coming) John Snow’s efforts to stop the spread of cholera in London’s Soho district during the 19th century. This story is like something out of public health Genesis: “And John Snow looked at the data, and he saw that it was good, and he called it ‘epidemiology.’” The documentary gives it a terrific refresh—it illuminates this history with an exceptionally detailed rendering of the <a href="https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/mapping-a-london-epidemic/" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">black-and-white map</a> Snow used to track cholera-related deaths in the town. (Skip to the 18-minute mark to check out the cool animated bird's-eye view of his famous map.) The map enlivens what is, at heart, a discussion of the advent of data collection as a core tenet of the field. The last quarter of the episode delves into race and ethnicity reporting issues, making for a nice segue into the third episode, “Inoculation & Inequity.”</p>

<p>In episode three, we are reminded of the history of public health injustices, such as (again, you know what’s coming) the Tuskegee syphilis study and the resulting mistrust between health care workers and people of color, particularly African Americans. The roots of distrust go much further back, as we hear from Lauren Powell, president and CEO of <em>The Equitist</em>: “We have plenty of evidence to show us that there is differential treatment between Black patients and white patients, that physicians often under-prescribe medication for Black patients and falsely think that we have thicker skin than white patients and therefore can tolerate more pain, which is directly connected to slavery.” Beautifully and succinctly said.</p>

<p>As a Black woman, I commend the directors for devoting an entire episode to how systemic racism has birthed numerous health care inequities for Black and brown folks. It’s a gravely significant issue; the filmmakers addressed it both boldly and sensitively.</p>

<p>Of course, we’re all aware of how COVID-19 helped push inequities to the forefront of the world’s collective consciousness. The pandemic also revealed some trials and errors of public health professionals and scientists—mistakes that, for many people, overshadow how quickly the scientists created vaccines and stopped the spread of the coronavirus. The question now is: Can public health do better?</p>

<p>The final episode, “The New Playbook,” seeks to answer that question—but falls a bit flat in its efforts to do so. We are told we should do things like hire chief health strategists, create better data analytics, alleviate stress for public health workers, and invest in more resources for the field. What we don’t hear enough about is how. Do we, for instance, give them mental health days? What would it take to offer those workers free mental health services? How can we get people to put community interest ahead of individual interest? How can we ensure that people don’t just think “the pandemic is over” and forget what a mess things were four years ago? In a series that sometimes seemed to go on too long, this episode left me wanting more.</p>

<p>The series features many of the field's brightest and most influential minds, which allows viewers to appreciate the breadth and scope of the field. But there are almost two dozen of them spread across a little over three-and-a-half hours of footage. It’s like the Marvel Universe invaded a public health documentary, so you are constantly trying to remember who used what superpower back in issue 74.</p>

<p class=" t-has-endmark t-has-endmark">Still, <em>Invisible Shield </em>is worth watching, if only because it tells some good stories, a skill desperately lacking in public health. Ideas are for the most part clearly articulated, and there are captivating graphics in each episode.</p>

<script async src="https://www.googletagmanager.com/gtag/js?id=G-S1L5BS4DJN"></script>

<script>

window.dataLayer = window.dataLayer || [];

if (typeof gtag !== "function") {function gtag(){dataLayer.push(arguments);}}

gtag('js', new Date());

gtag('config', 'G-S1L5BS4DJN');

</script>

Republishing guidelines

We’re happy to know you’re interested in republishing one of our stories. Please follow the guidelines below, adapted from other sites, primarily ProPublica’s Steal Our Stories guidelines (we didn’t steal all of its republishing guidelines, but we stole a lot of them). We also borrowed from Undark and KFF Health News.

Timeframe: Most stories and opinion pieces on our site can be republished within 90 days of posting. An article is available for republishing if our “Republish” button appears next to the story. We follow the Creative Commons noncommercial no-derivatives license.

When republishing a Harvard Public Health story, please follow these rules and use the required acknowledgments:

- Do not edit our stories, except to reflect changes in time (for instance, “last week” may replace “yesterday”), make style updates (we use serial commas; you may choose not to), and location (we spell out state names; you may choose not to).

- Include the author’s byline.

- Include text at the top of the story that says, “This article was originally published by Harvard Public Health. You must link the words “Harvard Public Health” to the story’s original/canonical URL.

- You must preserve the links in our stories, including our newsletter sign-up language and link.

- You must use our analytics tag: a single pixel and a snippet of HTML code that allows us to monitor our story’s traffic on your site. If you utilize our “Republish” link, the code will be automatically appended at the end of the article. It occupies minimal space and will be enclosed within a standard <script> tag.

- You must set the canonical link to the original Harvard Public Health URL or otherwise ensure that canonical tags are properly implemented to indicate that HPH is the original source of the content. For more information about canonical metadata, click here.

Packaging: Feel free to use our headline and deck or to craft your own headlines, subheads, and other material.

Art: You may republish editorial cartoons and photographs on stories with the “Republish” button. For illustrations or articles without the “Republish” button, please reach out to republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.

Exceptions: Stories that do not include a Republish button are either exclusive to us or governed by another collaborative agreement. Please reach out directly to the author, photographer, illustrator, or other named contributor for permission to reprint work that does not include our Republish button. Please do the same for stories published more than 90 days previously. If you have any questions, contact us at republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.

Translations: If you would like to translate our story into another language, please contact us first at republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.

Ads: It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads, but not ads specifically sold against our stories. You can’t state or imply that donations to your organization support Harvard Public Health.

Responsibilities and restrictions: You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third-party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. Harvard Public Health recognizes that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties aggregate or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

You may not republish our material wholesale or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You may not use our work to populate a website designed to improve rankings on search engines or solely to gain revenue from network-based advertisements.

Any website on which our stories appear must include a prominent and effective way to contact the editorial team at the publication.

Social media: If your publication shares republished stories on social media, we welcome a tag. We are @PublicHealthMag on X, Threads, and Instagram, and Harvard Public Health magazine on Facebook and LinkedIn.

Questions: If you have other questions, email us at republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.