Feature

A program treating gun violence as a contagion loses funding

This story was originally published by MLK50: Justice Through Journalism. Subscribe to their newsletter here.

“Alright, alright now. How you doing?”

It was a late-summer afternoon, and Dedrick Chism, 48, was motoring around New Horizon Apartments in a golf cart.

“What, what!” he greeted an older gentleman seated in a lawn chair beside a blue pickup truck, enjoying a beer in the Memphis heat.

He drove by the field in the Whitehaven apartment complex where, as a supervisor at Heal 901 Cures, he hosts youth football games; then he rolled by the courtyard where the program had screened a cartoon, “The Bad Guys,” for residents.

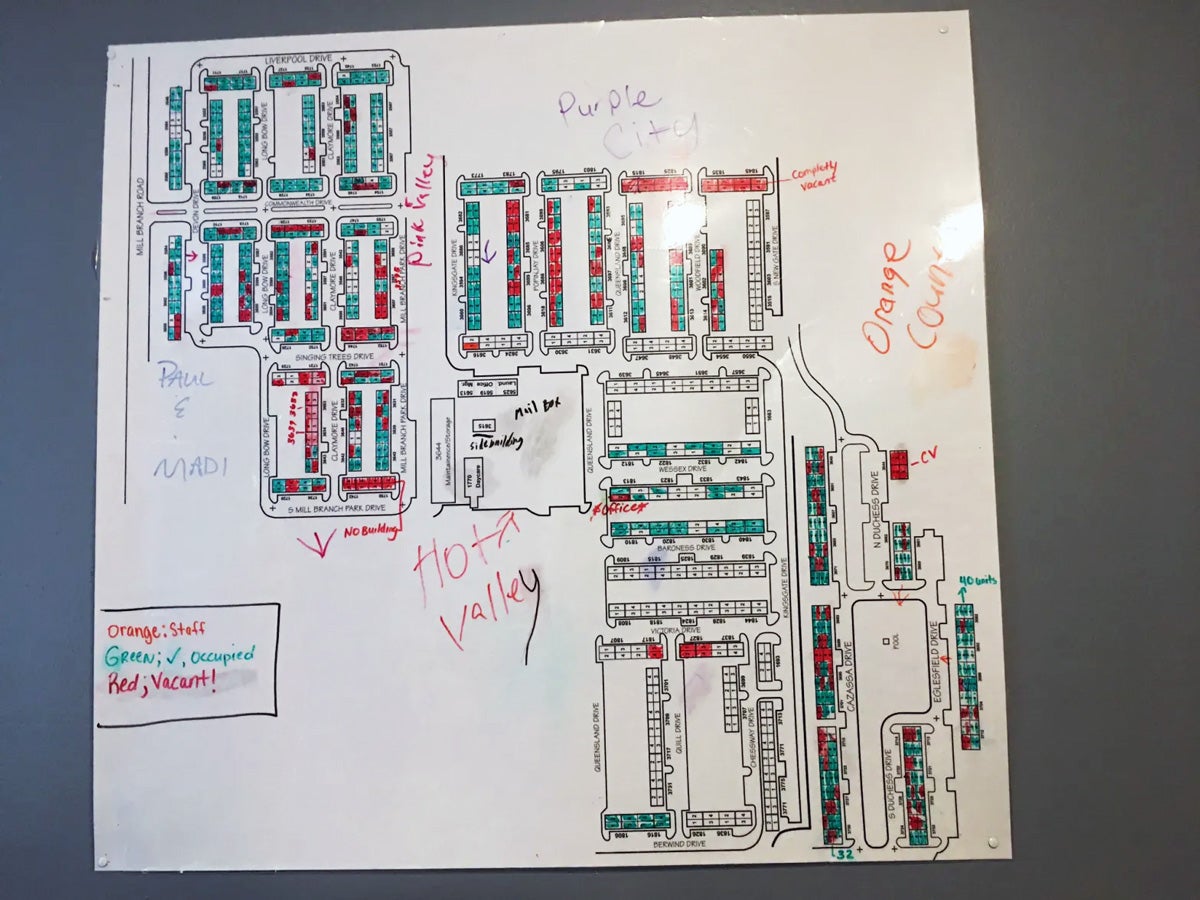

All looked peaceful, but Chism said that at six or seven o’clock, once kids were back from school and people began congregating around the outdoor mailboxes, conflicts could occur. So much so that one of his colleagues calls the mailbox area Hot Valley, for the way disturbances can heat up in a flash.

These conflicts are the main reason Heal 901 Cures is at New Horizon—to try to reduce violence with the help of people like Chism, a former gang member who grew up in Orange Mound. People who understand the roots of the problem, because they’ve been there themselves.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

In Memphis, and particularly during the mayoral race, crime is a constant topic. Solutions have often focused on punitive and surveillance approaches: longer prison sentences and hiring more police.

Yet there is little talk of the community-based models that form the foundation of programs such as Heal 901 Cures. Research indicates that such violence intervention programs have helped significantly reduce shootings in cities around the world, from New York to Baltimore to Cali, Columbia; the approach also shows some hopeful signs in Memphis’s Whitehaven neighborhood.

But after a short six-month trial period, Heal 901 Cures’ funding from the Shelby County Health Department has ended.

“We’ve been put in a position where we can be crippled, without sustainability,” the program’s executive director K. Durell Cowan said.

A public-health solution

Memphis, like many cities around the country, saw a spike in homicides during the COVID pandemic, reaching a high in 2021 of 346 homicides, which declined last year by 12.7%. But violent crime spiked during the first quarter of 2023, according to data released by the nonprofit Memphis Shelby County Crime Commission, with murders up 77% compared to the same period last year and gun-related violence up 10.9%.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, homicide is the leading cause of death for Black males 44 years old and younger. Yet gun violence affects not only victims but entire communities—the families and friends of victims and perpetrators alike.

Shelby County Health Department health director Michelle Taylor believes that the all-encompassing quality of gun violence requires a public-health approach.

“Instead of deciding that the only way to deal with crime is more law enforcement or more jails, let’s have a serious conversation about what it’s going to take … to approach this from a holistic point of view,” she said in a recent phone interview.

A holistic approach, she said, would include taking into account a community’s history and looking at the root causes of violence; it might require addressing the need for a supportive family environment, early childhood education and mentorship.

K. Durell Cowan, founder of Heal 901.

Photo: Brandon Dill for MLK50

In January 2020, Taylor’s predecessor at the health department, Alisa Haushalter, had begun thinking about what a public health strategy might look like. The department began talks with Cure Violence Global, an organization with international expertise in violence reduction. It would act as a consultant while a local group would carry out the on-the-ground program.

The global pandemic interfered with any hopes of a quick start to those plans. But last year, the health department chose the nonprofit community organization Heal 901 to run the program locally. Heal 901 Cures, a six-month pilot, was born.

Cure Violence Global vetted workers and provided analysis and support, with regular visits to Memphis from its Chicago headquarters. Funded by the U.S. Department of Justice and overseen by the health department, the pilot hired its current staff in January. In early February, it had “boots on the ground,” as Cowan, founder of Heal 901, put it, with a ramp-up period that began in October. Cowan said Heal 901 was paid $640,000 for the pilot.

The 11 program employees — including frontline workers, administrators, managers and other staff — receive a minimum of $22 per hour, a living wage in Memphis for a household of two working adults with two children (though a national criminal justice expert said the salary was on the low end for frontline workers nationwide).

Violence viewed as a contagious disease

Heal 901 Cures is the smallest and newest of three “violence intervention” or “violence interruption” programs currently operating in Memphis—one (901 BLOC Squad) is run by the city, another (Memphis Allies) by the nonprofit Youth Villages, with multimillion-dollar philanthropic funding. All are fairly similar in their focus on high-risk individuals and using intensive follow-up provided by former offenders. The Cure Violence Global model is particularly attractive to health departments and other agencies that want to take a public health approach to gun violence, in part because of its scientific model.

First implemented in 2000 to address violence in Chicago by epidemiologist Gary Slutkin, former head of the World Health Organization’s Intervention Development Unit, the Cure Violence method treats violence, metaphorically, as a disease.

“Cure Violence Global’s approach is based on the understanding that violence is a contagious problem,” said Monique Williams, executive director of Cure Violence Global. Its strategies are modeled on those used to treat health epidemics such as cholera, TB, or COVID.

The method seeks to stop the spread of violence by detecting and interrupting conflicts, identifying and treating the individuals at the highest risk of committing gun violence (generally thought by experts to be a very small percentage of a community, in the single digits), and changing the norms that allow violence to flourish.

“Violence interrupters” directly intervene to stop the transmission of conflicts, while outreach workers work one-on-one with individuals identified as high risk to help them identify life goals and orient them toward new ways of behavior.

A 2014 two-year analysis of the local Chicago program (called Ceasefire) by the University of Chicago found a 31 percent reduction in homicide and a 19 percent reduction in shootings in the areas covered by the program. The report found that the reductions were “significantly greater” than what could have been expected without the program, even given declining crime in the city as a whole at the time.

From children fighting to ‘now a gun is in somebody’s hand’

Far from Hollywood stereotypes of inner-city drug-turf wars, many more shootings are the result of interpersonal “beefs,” gun violence experts say.

Cowan said that a big problem can start small.

“There’s been situations that we had to defuse and it went just like this: It went from a children’s fight to the siblings coming out, to the parents coming out, to now a gun is in somebody’s hand,” Cowan said. “You put people in a confined area with limited resources, where they struggle on a daily basis—if you look at me the wrong way, that’s enough to cause a problem.”

During an initial assessment period, Cure Violence Global quickly identified the Whitehaven neighborhood as the area to concentrate on.

“The data was pretty clear on the area,” said Brent Decker, Cure Violence Global’s chief program officer, referring to the high amount of gun violence, over time.

Because the other two violence intervention programs in Memphis were located in North Memphis, another hot spot, it made sense for the Cure Violence program to focus on a different cluster of violence. The target area was further narrowed to just one apartment complex—New Horizon Apartments, formerly the notorious Kingsgate Apartments and still home to the Kingsgate Mafia gang.

Heal 901 Cures workers were well aware of the community’s reputation. (During one three-month period in 2017, New Horizon had the dubious distinction of being the apartment complex where Memphis police responded to the most calls.)

“If you know anything about the Kingsgate, it’s been real dangerous over here when we were young,” said Heal 901 Cures supervisor Chism.

Current Tennessee gun laws only exacerbate problems today.

Heal 901 Cures outreach worker Alex Brent, who gave Hot Valley its moniker, remembers what it was like early in the pilot program.

“Hot Valley is where we have a lot of problems, but it’s slowing down because when we first came in here, oh man, it was like Beirut,” he said. “You seeing a young man walk around with an assault rifle … carrying it in broad daylight. There’s children outside, there’s elderly people trying to go to their mailboxes.”

“The gun laws, they just made a big mistake with that. Anybody can just have a gun without a license, just hold it and openly carry it,” Chism said, referring to the 2021 law that allows adults to carry a handgun, openly or concealed, without a permit.

A Heal 901 Cures map of New Horizon Apartments, with the trouble zone, nicknamed Hot Valley, indicated in the center.

Photo: Sono Motoyama for MLK50

The 57-acre New Horizon property, with 902 apartments and over 2,000 residents, is so large that violence interruption staff surveys the property in golf carts, or, when it’s too hot, in cars.

Generally, two teams of two canvass the complex from Tuesday through Saturday, working from 2 p.m. to 10 p.m.

Program employees say residents’ change in attitude toward Heal 901 staff since the start of the program has been dramatic. Initially suspicious, apartment residents now greet them by name, telling them about problems and approaching Heal 901 Cures staff instead of apartment security to resolve conflicts.

“In the process of mediating situations, that’s how we have found our way into a lot of people’s hearts, by the way that we handle situations,” Chism said. “We try to build a relationship with them. You have to talk to people, especially kids. You have to let them know that you are here for them.”

In his late afternoon ride around the New Horizon property, Chism queried an older man about Heal 901 Cures’ impact.

Of the residents, the man answered, “They don’t need your money. They don’t need your food. They just need your love.”

Heal 901 said that there have been no homicides while they were on duty at the complex since the program began. “But when we get off work, you might hear shooting,” Cowan said.

According to Memphis Police Department statistics, during the period the Heal 901 Cures pilot was officially in operation, there was one murder and 165 incidents in the quarter-mile area surrounding New Horizon Apartments. (A quarter mile is the smallest area the public safety map covers.) During the same period a year earlier, in 2022, there were two murders and 162 incidents, making the two years roughly equivalent, according to this raw data.

‘Like an ambulance service’

Heal 901 Cures does not stop at mediating conflicts and aiding high-risk individuals, Cowan said.

The group has helped people get jobs, enter into vocational or post-secondary training, run clinics to help eligible convicted criminals expunge their records (which may help in getting a job and retrieving voting rights).

Cowan’s employees talk about setting up flag football games for youth, helping an elderly woman address a longstanding mold problem in her apartment, paying for a drug addict to enter rehab and reconnect with his family.

“Those are impacts that you can’t quantify in data,” Cowan said.

Of the pilot’s seemingly all-encompassing role, he said, “we’re more like an ambulance service. We stop the bleeding right now and we’re going to get you in a situation where you’re stable, where you can get the more intensive care you need.” This means connecting neighborhood residents with a variety of other services and nonprofits.

It might even mean a mind-expanding trip to the National Civil Rights Museum. “It’s like we were out of town in another world,” Chism said of taking program participants to the landmark.

The health department’s Taylor also pointed to the program’s wraparound services as successes. She cited stopping nine potential shootings; intervention in 83 verbal disputes without violence breaking out; 140 job referrals, 68 of them successful; the expungement of 11 criminal records; referrals for driver’s license reinstatement; six employment fairs; referrals for healthcare and other services.

Having even one former offender find a job that allows them to take care of their family or themselves “is a huge win, not only for that individual and their family but for the community,” Taylor said. The department is “proud,” she said that it had helped Heal 901 build its organization so it can continue violence interruption work in the future.

There were no specific goals the program was expected to meet to define its success, she said.

The six-month pilot officially ended in June, and Heal 901 Cures has waited for county officials to decide its fate. In the interim, it has paid out of pocket for the continuation of the effort, with the help of a $50,000 grant from the Kresge Foundation. (MLK50 is also a recipient of Kresge Foundation funding.)

When asked about the continuance of the program, Taylor said that going forward, the department would focus on gathering data on “upstream factors” to make future interventions more effective. It will examine child delinquency, child welfare and risk and protective factors for criminal involvement and recidivism. The department hopes to answer these questions to make the case for continued violence intervention and prevention programs, and to inform the ongoing violence intervention programs led by various groups in the city, Taylor said.

As for Heal 901 Cures specifically, “if we are able to identify additional funds for violence intervention and prevention work,” Taylor said, “Heal 901 will have the opportunity to apply for those additional funds.”

For the moment, however, “our partnership with them and the funding partnership with them has ended,” she said.

Shelby County Health Department director Michelle Taylor.

Photo: Andrea Morales for MLK50

A long-term strategy

Despite the multiple needs of the New Horizon community, which Heal 901 has sought to address, some express concerns about Heal 901 Cures’ comprehensive approach.

David Muhammad is executive director of the National Institute of Criminal Justice Reform, which issued a report on Memphis gun violence as part of the White House Community Violence Intervention Collaborative. The NICJR is also a consultant with Youth Villages’ Memphis Allies, among other gun violence reduction programs nationwide.

He said that it is not unusual to see gun violence programs address other social problems. However, “it is a challenge because if the goal is to reduce gun violence, while many of those services will be very helpful to the community, many don’t lead to gun-violence reduction.” In his eyes, the focus must be on high-risk potential offenders if the aim is to reduce shootings.

Another issue, Muhammad said, is the sustainability of the project. “If they’re being asked to reduce violence with a six-month pilot project, that’s an extremely difficult task. Some of my colleagues would call it impossible.”

When asked if it is possible to judge the success of a violence reduction program in six months, Cure Violence Global executive director Williams agreed with Muhammad: “Absolutely not,” she said. “It’s just too new. They’re going to run into bumps. They’re going to have to course-correct as they see what works and what doesn’t.”

“If you think about how long it’s taken us to get where we are, I think to expect a project to turn that around in six months is not realistic,” Brent Decker added. “This has to be part of the long-term strategy.”

Even Taylor concurs.

“From talking to other health department directors from across the country who have had the Cure Violence Global framework used in their communities for a lot longer than here in Shelby County, they have all told me to a person that they weren’t seeing true hard and fast outcomes for about five to seven years in program,” she said.

In Shelby County, the county commission decides whether to fund an initiative, and the decision is then submitted for the county mayor’s approval.

“When you’re talking about these types of issues, you also have to have the political will of multiple people who make these types of funding decisions to stay the course,” Taylor said. A holistic, “true” public-health approach “doesn’t happen in six months.”

Slow and steady wins the race

In his work, Cowan is used to preaching the values of constancy and patience. He has to convince teenagers in low-income neighborhoods, who have few role models, that they have a future. It’s hard to persuade an 18-year-old to work for $17 an hour at Walmart when they see their friend down the street get $5,000 for stealing a car, he said.

“You’re talking about 14-year-old children stealing three, four cars a week to make $15,000 to $20,000 a week. And you’re telling them to go get a job to make $36,000 a year.”

Being a living example and consistency are key, he believes.

One of Cowan’s go-to analogies is the fable of the tortoise and the hare. “Eventually, slow and steady wins the race,” he said. “The streets don’t come with a 401k, don’t come with a retirement plan or life insurance.”

He hopes, through repetition, the message will get through.

The patience that Cowan is trying to teach others may be necessary for his own organization as it navigates the future. When told last week that Shelby County currently viewed its funding partnership with Heal 901 Cures as over, Cowan said he was not surprised.

However, he said he has other irons in the fire. He said he was in talks with the Shelby County District Attorney’s office, Youth Villages and Shelby County schools about possible future partnerships. His organization was in a “great position,” he said, to continue its work, and the end of the health department contract frees it to pursue other endeavors.

Cowan said he is still committed to continuing the program at New Horizon, as long as the proprietors allow it. Or rather, as he put it, “I’m committed to the people, to the community, to the kids.”

“When funding stops, we understand there’s a dire effect that it has on the community,” he said. “Everyone has seen people move in and out of their lives so much that that has to stop.”

Top photo illustration: Andrea Morales for MLK50