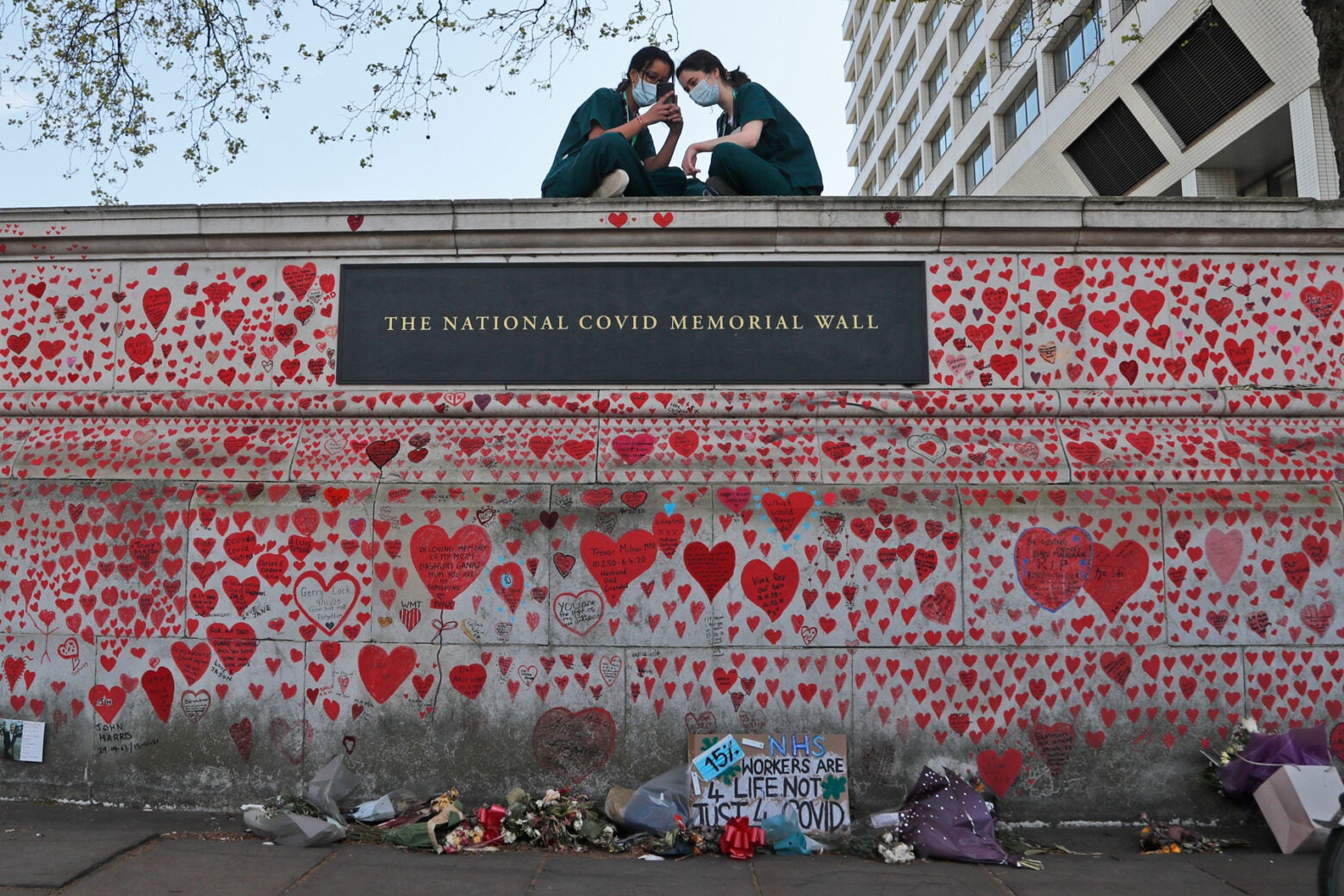

Two nurses sit atop a section of the National Covid Memorial Wall in London in April 2021, about a month after volunteers from the COVID-19 Bereaved Families for Justice started painting hearts to represent the 245,000 Britons who died from Covid. The wall of hearts is roughly a third of a mile in length and faces the Palace of Westminster, home to the British Parliament. Frank Augstein / AP Photo

Feature

Even great data couldn’t solve the UK’s COVID woes

When the first wave of COVID-19 infections hit the United Kingdom in February 2020, the country’s politicians and scientists, like those everywhere, lacked the data needed to understand the situation. The UK wasn’t even clear on how many hospital beds it had, says Matt Hancock, the country’s health secretary at the time. “The first thing we had to do,” he says, “was agree on the definition of a hospital bed.”

But the UK very quickly created what has been called one of the world’s best data responses to the pandemic. Still, nearly a quarter-million Britons died from Covid. An ongoing public inquiry seeks to find out why—but it is already clear that politicians struggled with balancing the economic and social disruption of locking down the country against the rising death rate.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

At the start of the coronavirus crisis in January, the UK mobilized its Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, or SAGE, a group of roughly 20 public health officials and scientists formed specifically to advise on the crisis. Unlike in the United States, where data sources were so fragmented that it was hard to build a clear picture of the pandemic, SAGE initially pulled together available data and played a key role in information gathering and informing the response, eventually meeting more than 100 times during the crisis. At the start, the group understood the problem it faced: “We didn’t know exactly where we stood with the epidemic, how quickly was it growing,” says John Edmunds, a SAGE member and infectious disease researcher at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

SAGE immediately called for setting up a host of surveillance studies and research projects. By early February it had working models good enough for the SAGE team to form a consensus around how to suppress the spread of the virus: Reduce contacts in the community by 75 percent.

“A week is a long time when the doubling time of the epidemic is two days. A month is an eternity. Not making a decision is a decision itself.”

SAGE member Jeremy Farrar

How to achieve this was less clear. Patrick Vallance, SAGE’s cochair and Boris Johnson’s chief scientific advisor, told the inquiry that there were concerns from medical advisors about the impact of lockdown on mental health and on care for patients who didn’t have Covid. Operational factors such as getting policies and legislation in place also played a part in the delay.

Johnson, in a written statement submitted for the inquiry, said he feared the economic effects of a complete lockdown could cause public dissent. “Science could guide us and help us but many of the decisions would involve such complex moral and political dilemmas that only elected politicians could take them,” Johnson wrote. He authorized other steps to restrict interactions.

Boris Johnson (center), then the United Kingdom's prime minister, at a March 16, 2020 press conference on the coronavirus response. Also there were Chris Whitty (left), England's chief medical officer, and Patrick Vallance, Johnson's chief scientific officer.

Richard Pohle / Pool via AP Photo

By late March, it was clear that those steps had failed. Johnson and his team had in late February and early March been presented with models projecting that the UK could face more than half a million deaths from Covid. “We could see the shape of the curve,” says Hancock, but it was difficult to tell whether the cost of not acting was higher than taking the unprecedented step of locking down. Johnson finally instituted a lockdown on March 23.

That decision came too late for some observers, who say the data had been suggesting locking down for weeks. “The political and policy decisions were too slow,” says SAGE member Jeremy Farrar, now chief scientist at the World Health Organization in Geneva. “A week is a long time when the doubling time of the epidemic is two days. A month is an eternity. Not making a decision is a decision itself.”

How to build a great pandemic response system

As the pandemic raged through the spring of 2020, SAGE was readying a robust data arsenal. Three projects in particular became invaluable to that effort: genome sequencing of the virus; a Coronavirus Infection Survey; and the Recovery Trial, a clinical study that helped researchers identify which treatments worked best against severe Covid.

The Recovery Trial initially enrolled 40,000 people across 185 sites in the UK and identified dexamethasone, a cheap and readily available steroid, as one of the first effective treatments for Covid. Estimates suggest that within a year of the trial’s start date, the drug had saved the lives of 22,000 Covid patients in the UK, and one million worldwide.

The Coronavirus Infection Survey (CIS), meanwhile, was a random sampling exercise led by Farrar and officials from the Office of National Statistics and set up in just 10 days. Launched April 26, 2020, it tracked symptoms by age and region and estimated the average number of new cases per week. At its peak, the CIS was collecting 400,000 samples per month. The project “was virtually unique around the world,” says Edmunds. It would become fundamental to the pandemic response in the UK, where policymakers showed its graphs in nightly televised press conferences. The World Health Organization also used the data to help measure the pandemic globally, says Emma Rourke, the UK’s deputy chief statistician.

Genomic scientists started discussing creating a network to rapidly sequence samples of SARS-CoV-2 recovered from patients in February 2020, seeing it as a tool to track how the virus was spreading and mutating. Some researchers resisted because coronaviruses tend not to mutate as quickly as other viruses, meaning there might not be enough variation within the samples to trace outbreaks.

But the genomic scientists’ group, which became known as COG-UK, decided it was a risk worth taking and secured a £20 million (about $23 million U.S.) grant from the government to set up a consortium of nationwide sequencing hubs. Samples came from the National Health Service, public health laboratories, and Covid testing centers. At its height, COG-UK was registering more than 50 percent of the SARS-CoV-2 sequences in the world.

Data vs. disease

Despite the lockdown and SAGE’s work, by early May the UK had the highest Covid death toll in Europe (when the UK later adopted different reporting criteria, that rate was more in line with those on the continent). It also had “the most comprehensive and informative data on Covid of any country in the world,” says Marc Lipsitch, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. That data was about to make a difference. The UK established a command-and-control hub for all things Covid, called the Joint Biosecurity Centre. Its dashboard was immediately helpful in pulling data together for use in decision-making. Combining the tools and data was “very, very powerful,” says Mark Woolhouse, an epidemiologist at the University of Edinburgh, who advised the Scottish government on its pandemic response, “much more valuable for informing policy.”

When the Office of National Statistics published the results of its first CIS on antibodies on May 28, it showed that only five percent of the UK public had developed antibodies to the virus, meaning overall infection rates were low. This knowledge “was critical for the strategy for how to get through,” says Hancock. It showed that it would have been “a disaster” to let the virus run its course, and it meant that ultimately, “there was no way out without a vaccine.”

Antibody surveys are critical tools in any pandemic scenario, Hancock says. The government also drew on data from the Covid testing service, the National Health Service, and research projects such as the REACT (Real-time Assessment of Community Transmission) study, another massive surveillance exercise led by Imperial College. Together they showed that infection rates had peaked in April, so officials could plot a course out of lockdown based on meeting thresholds for daily infection rates and a sustained drop in death rates. By mid-July of 2020, all lockdown restrictions were lifted.

Six weeks later, in September 2020, a second wave of the coronavirus emerged.

A nearly empty Piccadilly Circus in London on November 5, 2020, as England entered a four-week lockdown to stop the spread of the coronavirus.

WIktor Szymanowicz / NurPhoto via AP Photo

When the data doesn’t make a difference

By the second wave, SAGE—and UK politicians—had become comfortable working with the wealth of data they had. They had been able to draw on their dashboard to make recommendations about how best to protect public health. They had seen how to bring a lockdown to a close. But now they were faced with models suggesting the number of infections was growing two to seven percent per day, and a rapid increase in hospital admissions loomed.

SAGE’s team did the obvious: They called for tighter restrictions to curb the virus, including another short lockdown. But Johnson did not do that; instead, he introduced a series of measures including limiting social gatherings to six people, working from home for non-essential businesses, and establishing a 10 p.m. curfew for the hospitality sector. The government also announced a tiered system of restrictions by region, depending on local infection rates.

Hancock told Harvard Public Health that the wealth of data should have made the lockdown an easier call. But in the room where these decisions were made, other politicians opposed a lockdown. Johnson’s government wanted to limit the economic consequences of a complete lockdown. And in places that faced tighter restrictions under the tiered system, such as Manchester, leaders pushed back.

The SAGE group watched the political inertia with dismay. They had seen this happen in February and March. They knew the consequences of letting the virus spread unchecked through the population and feeling like the science was ignored. At the start, even the scientists could not predict the impact of a countrywide lockdown, but now they had robust models about the pandemic. “We didn’t want to make those same mistakes again. And, unfortunately, we [collectively] did,” says Edmunds.

Matt Hancock, the United Kingdom's Secretary of State for Health and Social Care between July 2018 and June 2021, wears a 'Protect The NHS' face mask on December 2, 2020. Days later the UK would begin vaccinating people against COVID-19.

Photo by David Cliff / NurPhoto via AP Photo

Farrar says it should have been clear: Follow the data. “The tragedy was having that brilliant data in July, August, September [of 2020] and seeing the wave developing, infections increasing day after day after day, and then not making a policy decision on the basis of data,” he says.

It wasn’t until November 5 that the government finally imposed a four-week lockdown across the whole of England (schools excepted) in order to prevent what Johnson would call a “medical and moral disaster” for the NHS. Less than a month later, on December 2, UK regulators approved a Covid vaccine. The country returned to the three-tiered restrictions within days.

Unfortunately, sequencing data from COG-UK had identified a new, highly transmissible mutation of Covid, the Alpha variant (also called the Kent variant, after the part of the UK where it was first seen). Cases soared in early January 2021. This time, Johnson’s government was quick to announce a third full lockdown, including schools, across England (Wales, Northern Ireland, and most of Scotland were also in lockdown).

As the vaccine rolled out across the country, data was capturing its effectiveness at preventing infection. Policymakers were able to use the data included in the dashboard to inform an easing of the lockdowns by July 2021.

Takeaways

The extent of any missteps could take until 2026 to be determined, as the inquiry will ultimately report on nine aspects of the UK’s Covid response, from the impact on young people to vaccines and therapeutics. Farrar says years of fiscal austerity meant the UK had neglected its public health infrastructure, leaving it without the capacity it needed to deal with a pandemic. The first report on preparedness, published in July, affirmed this point, finding that the UK was ill-equipped to deal with any catastrophic emergency. It also said the UK had planned for the wrong pandemic—a mild one. This meant it had not developed guidelines about using lockdowns in a pandemic, and politicians had to use the untested policy in the heat of the moment.

Jeremy Farrar, then director of Wellcome Trust, discussing lessons from the pandemic at the World Health Summit in Berlin in October 2021.

ddp images / Sipa USA / Sipa via AP Images

Despite criticism of the timing of the original lockdown in March 2020, Johnson told the inquiry the lockdown was data-driven and timed correctly. (Johnson tested positive for Covid soon after the first lockdown, winding up in intensive care before recovering.)

Even Johnson acknowledged that what happened in September 2020 was a mistake. He told the inquiry the one thing future leaders should do differently would be to focus on a UK-wide approach rather than a tiered policy.

The data effort drew praise. Edmunds calls gathering the data and expertise so quickly “amazing.” He says it showed “what you can do with political will, with money. It was absolutely transformative.”

The challenge for scientists came when they faced the unknown. He says scientists may have been too timid in pushing for lockdowns because they were so extreme. Hancock says the UK now knows lockdowns belong in the toolkit for fighting future pandemics, and politicians and scientists need to have agreements in principle on timing them. “As soon as you can see that the cost of action is going to be smaller than the cost of inaction, you must act,” he says. Separately, having an operational response ready to go is key for dealing with any future pandemic. This should include standing test capacity, contact tracing infrastructure, and the ability to set up clinical trials and vaccine challenge studies at pace, he says.

Hindsight is only so helpful, though. Edmunds says he still ruminates on the delays. “It’s a horrible thing. How much I am to blame versus other people further up the chain, I don’t know, but you feel it.”