Opinion

Five great health books for kids

Here are five recent books that look at public health topics from a child’s perspective.

Susan Schadt Press

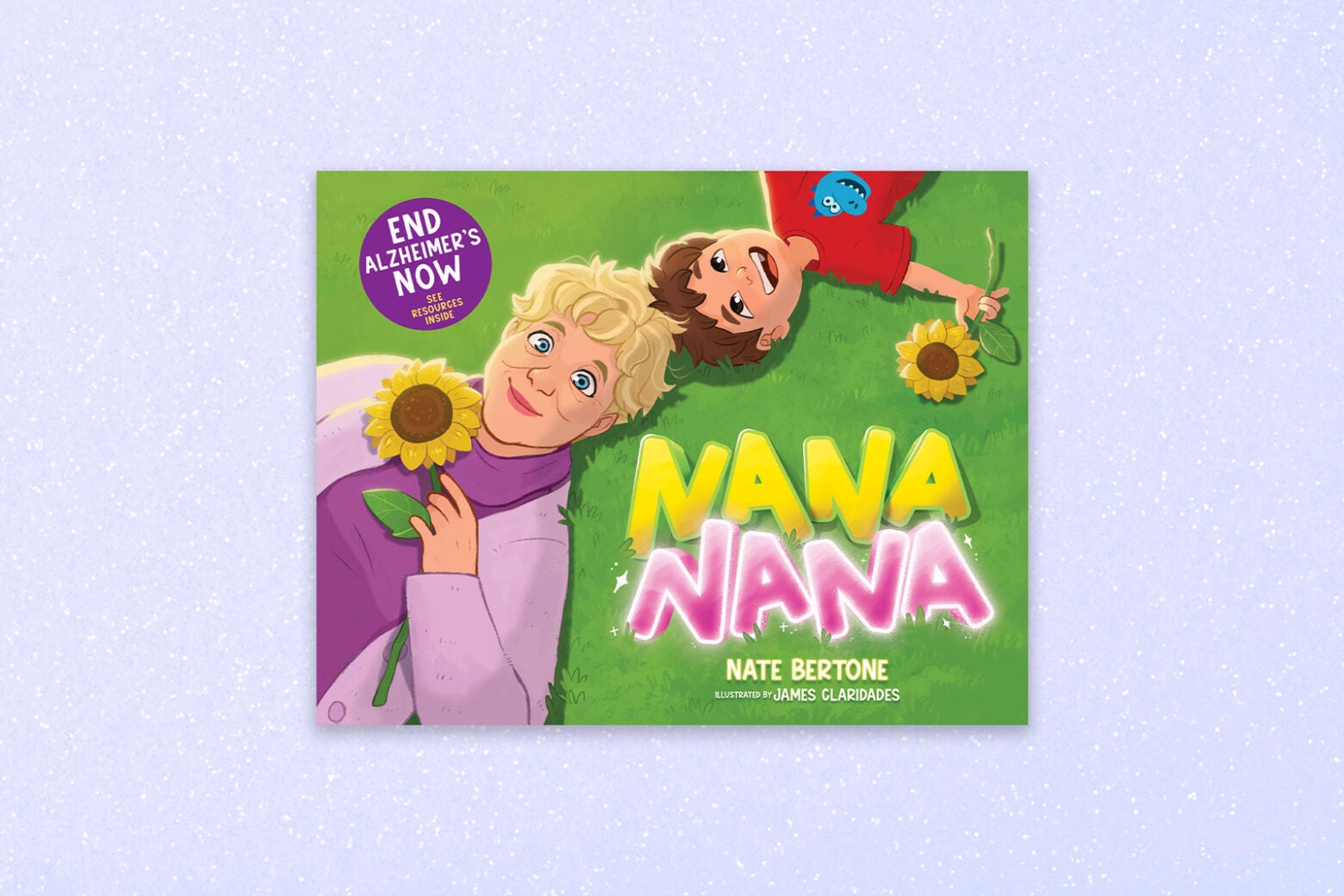

Nana Nana

By Nate Bertone

Illustrated by James Claridades

This story about the effects of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease touches on topics that can be scary for kids, including a beloved grandparent’s sudden outbursts of frustration and anger, their personality changes, and their inability to recognize them or remember their name. The book is eye-catching and engaging for younger kids and written at their level without speaking down to them. The colorful and lighthearted illustrations pair well with Bertone’s writing to make a potentially confusing topic more accessible for kids aged three to eight and their families.

Clarion / HarperCollins

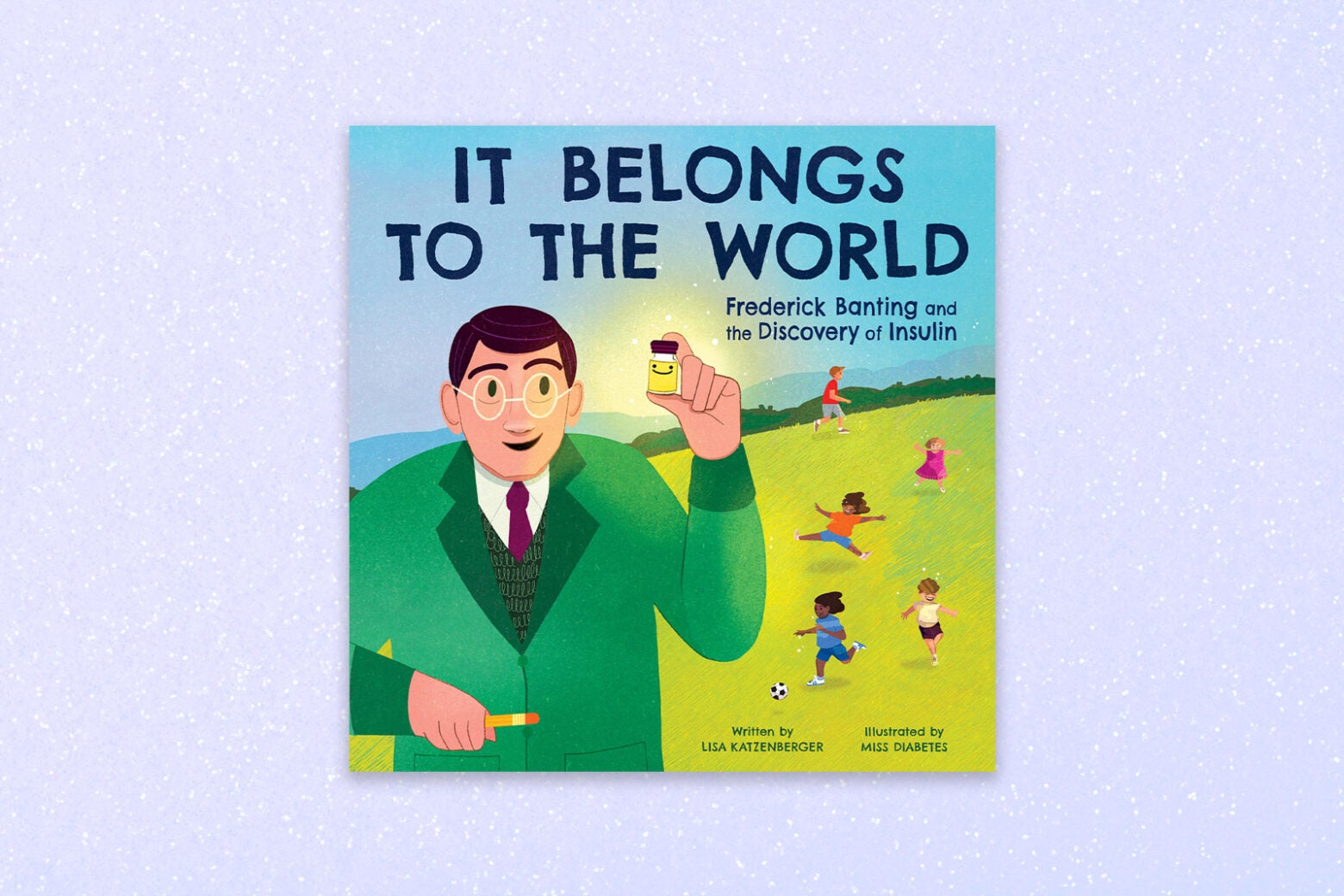

It Belongs to the World

By Lisa Katzenberg

Illustrated by Janina Gaudin (aka Miss Diabetes)

The story of Frederick Banting, the scientist who first identified and produced insulin, revolves around perseverance, curiosity, and selflessness. Banting’s scientific inquisitiveness and dedication help him push through numerous barriers and eventually identify insulin, the hormone messenger that controls blood sugar metabolism. He developed a treatment for diabetes and was told he could make a million dollars selling the recipe. He declined, saying, “Insulin does not belong to me. It belongs to the world.” The book offers an inspirational story for four- to 10-year-olds that demystifies diabetes. The book includes appendices on how insulin works that could help adults explain more to curious kids.

Acorn Cottage Press

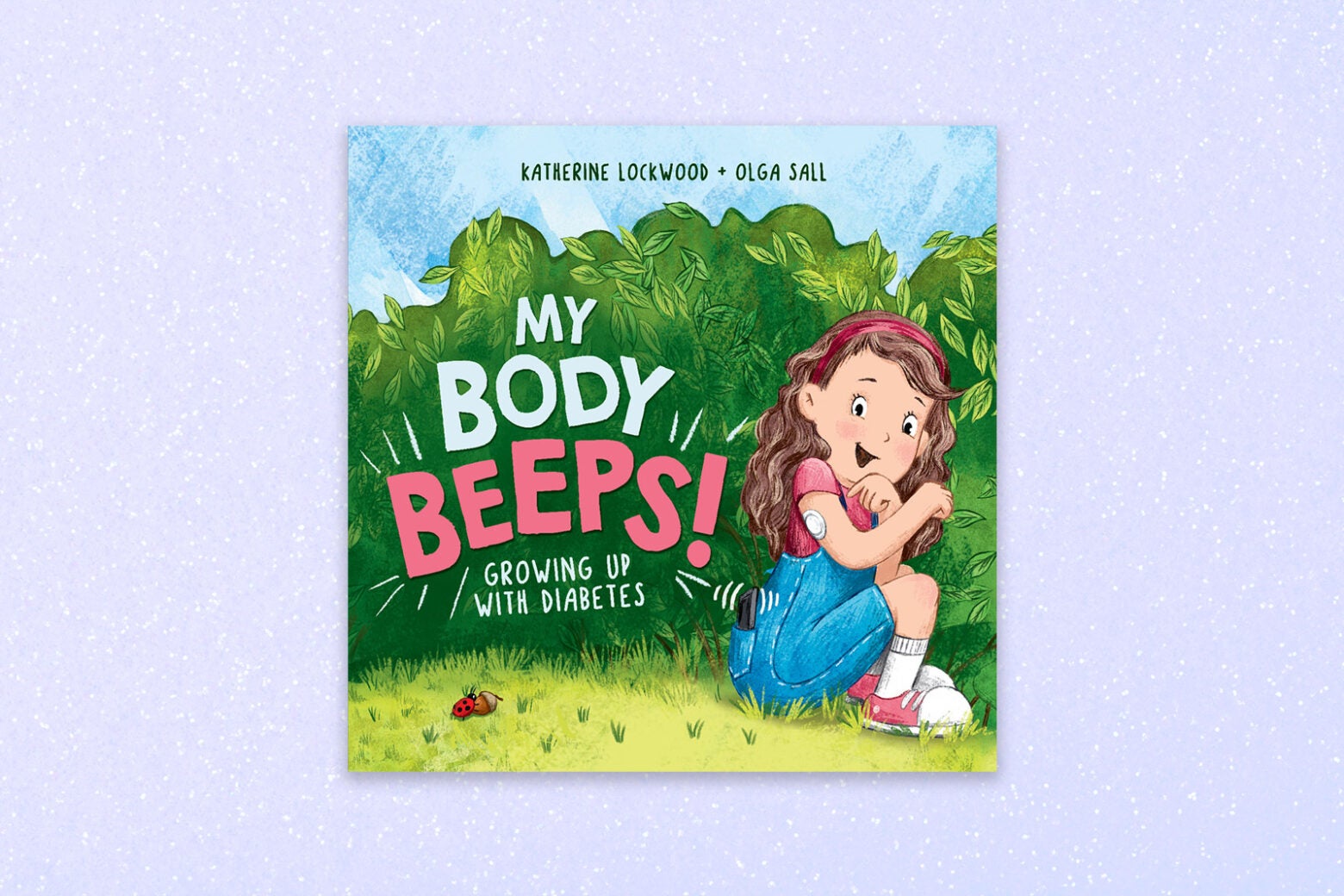

My Body Beeps

By Katherine Lockwood

Illustrated by Olga Sall

Katie has Type 1 diabetes and depends on a glucose monitor and insulin pump to stay healthy. As Katie plays hide and seek in the park, her glucose monitor starts beeping. Katie, irritated that the beeping could give away her hiding spot, ignores the monitor and feels ashamed for being different. Olivia, a new friend, joins Katie in her hiding spot and asks what the beeping is for. Olivia has asthma and uses her inhaler, which makes Katie feel better about having a glucose monitor. The book is written for three- to seven-year-olds and helps those who have Type 1 diabetes understand why it’s important to be responsible for their bodies’ needs.

MIT Kids Press

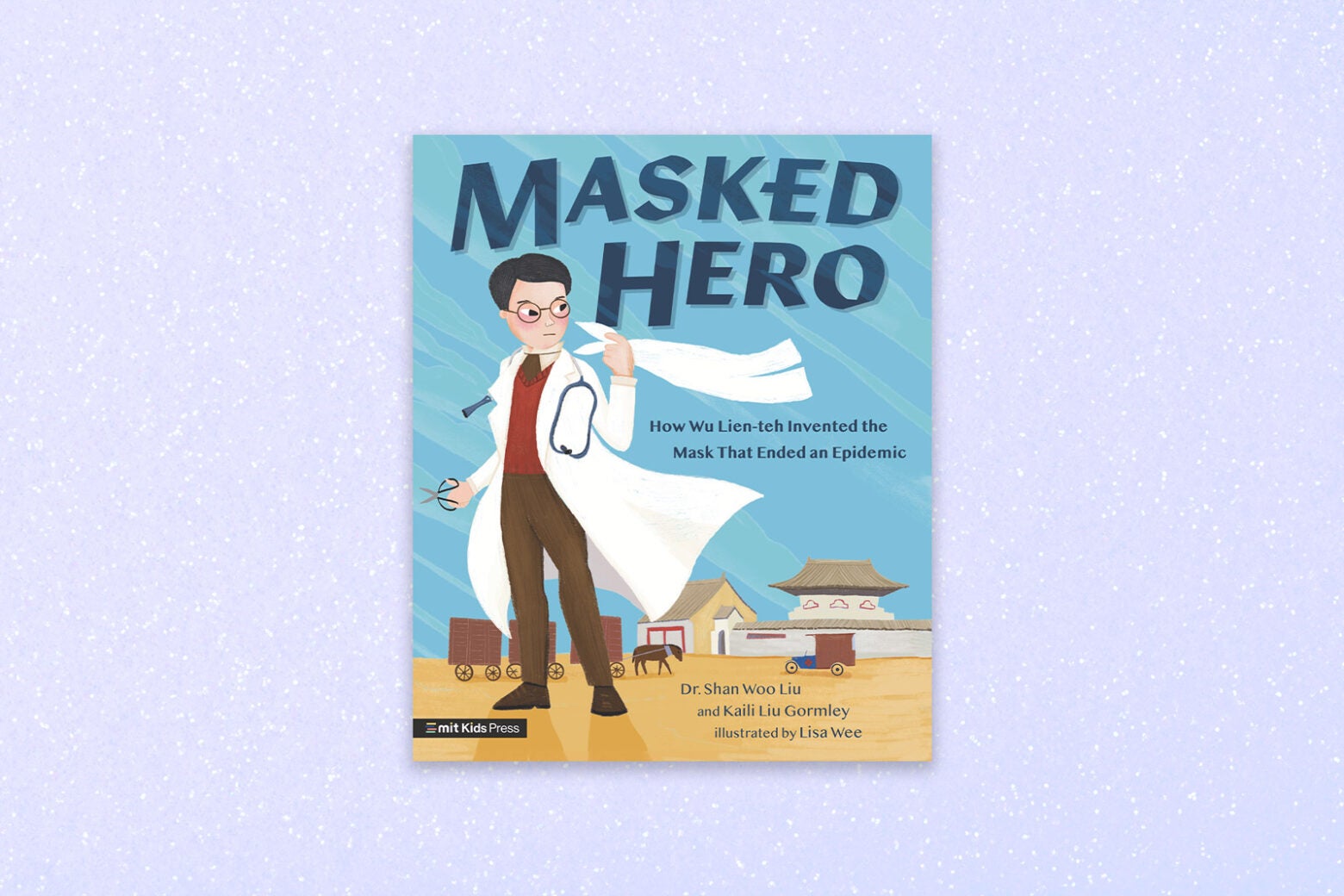

Masked Hero

By Dr. Shan Woo Liu and Kaili Liu Gormley

Illustrated by Lisa Wee

In 1910, a doctor named Wu Lien-teh was asked to travel to Northeast China to stop the spread of a mysterious disease. He suspected it was pneumonic—spread by breathing in bacteria—and created a sturdy, thick mask that covered the face except the eyes. Through masking, isolation, and travel restrictions he put in place, the outbreak of plague soon burned out—and made masks a tool for fighting certain diseases. The book, written by Wu’s great-granddaughter and great-great granddaughter, shows his dedication, ingenuity, and stubborn refusal to bow to racism and opposition. The illustrations are eye-catching and transport the reader along Wu’s journeys. The book, written for seven- to 10-year-olds, ends with a few discussion questions about problem-solving and public health.

Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

(Be Smart About) Screen Time!

by Rachel Brian

Being a kid can be hard, and Rachel Brian’s books, like Consent (for Kids!) and The Worry (Less) Book, provide guides for dealing with some big issues. (Be Smart About) Screen Time! features short chapters written in her usual humorous style accompanied by simple line drawings. The premise is to teach kids who’ve received a smartphone, tablet, or computer about risks and responsibilities, from caring for the device to judging which content to avoid. Boundaries around personal interactions are discussed in depth, as are trolls, bullies, and bots. So is nudity and what to do if it’s encountered (talk to a parent or another trusted adult). An excellent book for seven- to 12-year-olds, especially as a conversation starter about a family’s norms and expectations around devices, being online, and the potential mental health effects of social media.