Newsletter

HPH Weekly: Peter Hotez won’t be the last health worker harassed online

This edition of Harvard Public Health Weekly was sent to our subscribers on Jan. 25, 2024. If you don’t already receive the newsletter, subscribe here. To see more past newsletters, visit our archives.

Peter Hotez won’t be the last health worker harassed online

Last spring, a scientist and vaccine expert who criticized podcaster Joe Rogan was attacked online and stalked at his home. The year before, Boston Children’s Hospital received bomb threats because of its transgender care. And in the middle of the pandemic, a quarter of Americans believed it was OK to threaten a public health official, according to one study.

There aren’t yet many systemic solutions to the harassment public health workers can face on the job. But Samuel Mendez’s new Digital Safety Kit for Public Health can help mitigate the harm.

What is Fountain House? How does the clubhouse model work?

In a powerful op-ed, Aida Mejia praises the clubhouse model of care for valuing the ability of people with serious mental illness to make decisions for themselves. Clubhouses like Fountain House in New York City offer “a community where people support each other,” Mejia writes. Unlike the more conventional interventions she experienced, the clubhouse model prioritizes seeing past her illness to her strengths as a human being. That’s why she’s on a mission to expand the model: Clubhouses currently support 60,000 people in the U.S., but many more could stand to benefit from them, Mejia says.

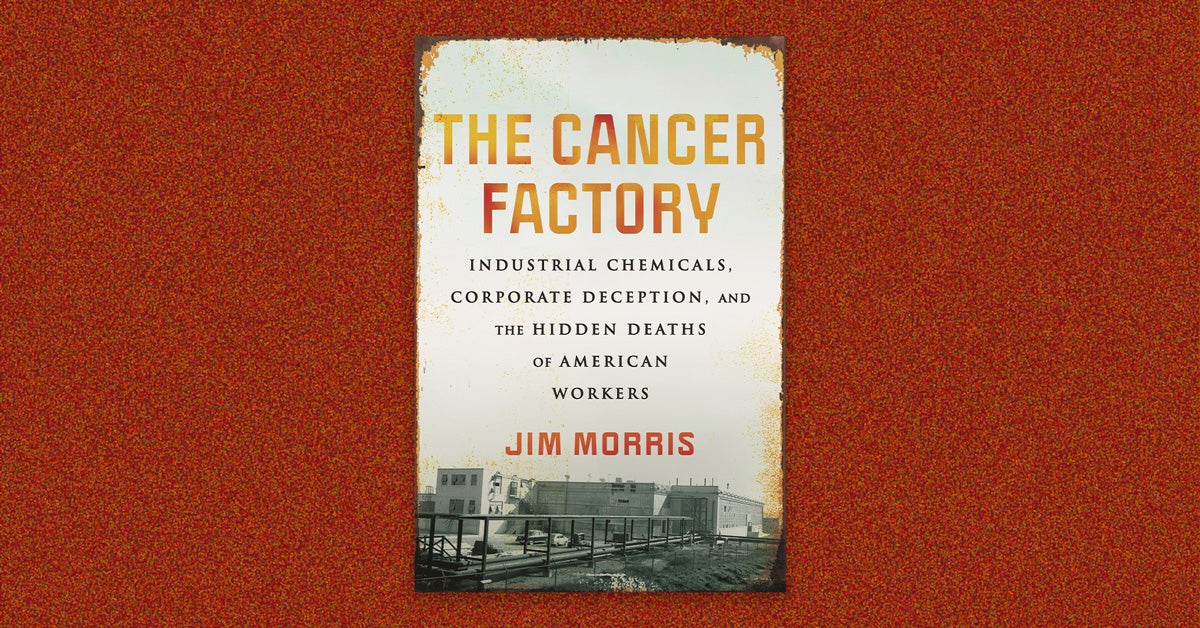

Jim Morris book review: o-toluidine and the DuPont cancer cluster

The chemical at the heart of Jim Morris’s The Cancer Factory first showed up in a New York factory in 1957, but its toxic power isn’t consigned to history. It’s contemporary. Morris chronicles the struggle of 78 workers who developed bladder cancer as a result of ortho-toluidine exposure at a factory that manufactures Goodyear tires. Despite well-documented evidence of the poisoning, reviewer Anna Young writes, weak federal chemical regulations—and resistance from corporations—have left the status quo around this deadly toxin intact.

Electric school buses are a breath of fresh air for children

Every weekday, more than 20 million kids ride to school on the bus. That means every weekday, they are exposed to the harmful pollutants emitted by vehicles that run on diesel fuel. The Biden administration has proposed more federal funding, via the Environmental Protection Agency, to help 280 school districts transition to electric school buses. Grist’s news and politics fellow Akielly Hu weighs in in favor of the proposal.

This article was originally published in Grist.

What we’re reading this week

- My family’s $2,000 popsicle and why health care costs so much in Colorado | The Colorado Sun

- India’s women brick kiln workers find health care elusive | Global Health Now

- In battle over e-cigarettes in Latin America, tobacco money quietly at play | The Examination

- At ‘Climate Cafés,’ mental health experts and environmentalists create a community | The Chicago Tribune

- The complicated lives and deaths of TikTok’s illness influencers | Vox

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.