Ideas

U.S. kids face a mental health crisis – a bold new law points to a solution

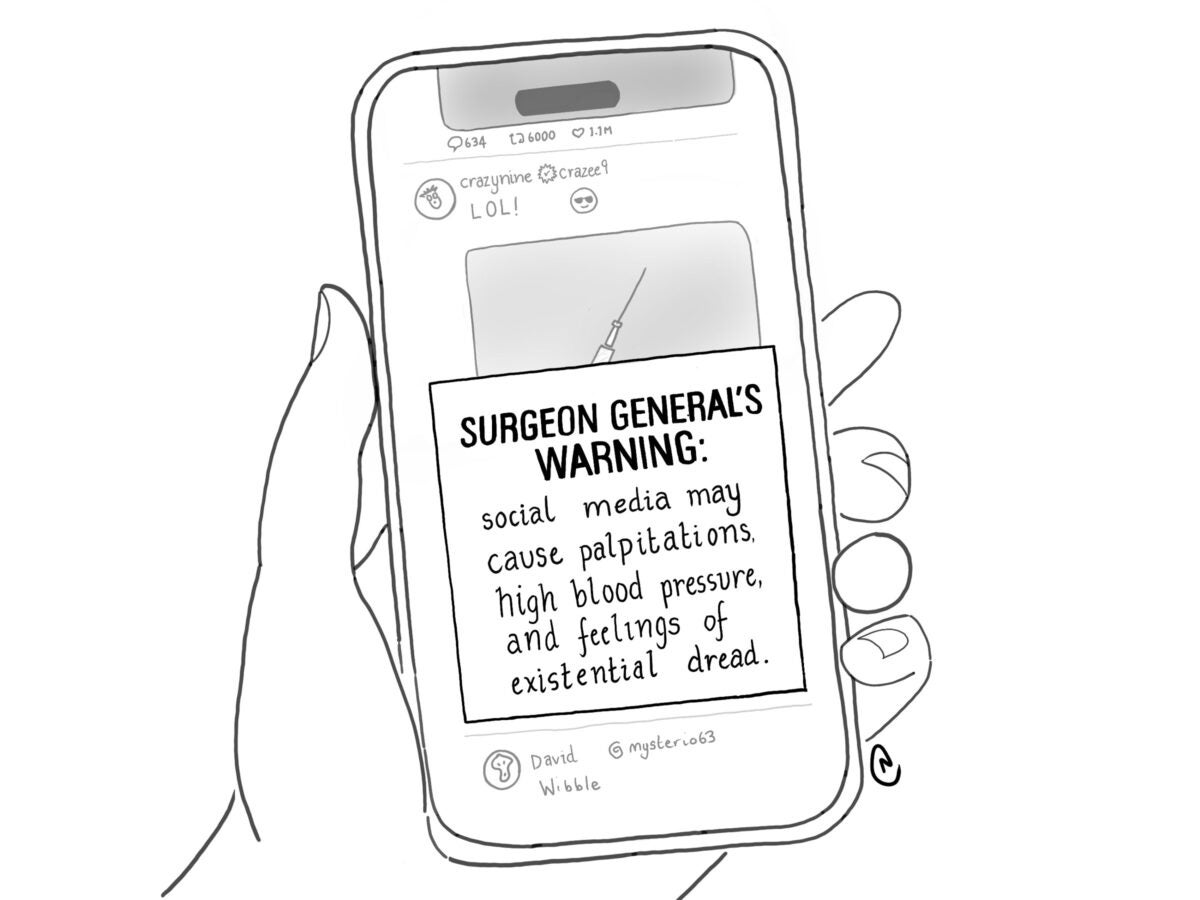

Over the past two years, I have seen the waiting list at my pediatric psychology practice balloon. More and more children are seeking help in the face of school closings, continued social isolation, and skyrocketing rates of harmful social media use. The state of mental health for U.S. children has steadily declined for a decade now, and last year the U.S. Surgeon General declared it a full-blown crisis.

I practice in Texas, the state with the worst access to mental health care in the nation. I know how critically we need change. Reform may be within our grasp.

Earlier this month, with little media fanfare, Delaware Governor John Carney signed a law that could transform mental health care in the state. Starting January 1, 2023, all insurance companies must cover an annual mental health wellness visit, just like they do for physical wellness checks.

This is good news for everyone still reeling from years of pandemic and social turmoil. Today, one in six children are diagnosed with a mental health disorder, and nearly 40% of teens reported persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness in the past year. But fewer than half will get the treatment they need. Across the country, very few children ever see a mental health professional for routine screening – like the Delaware law supports – meaning we don’t catch mental and behavioral health problems early. We also have a critical workforce shortage of mental health professionals nationwide, and inadequate insurance coverage for mental health. The Delaware law addresses all these obstacles.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

We know that the earlier we detect health problems, the more likely it is the illness or injury can be successfully treated. That’s why parents take their children to the pediatrician for a routine check-up every year.

Unfortunately, there is no equivalent to an annual physical in the mental health space (except now for Delaware). Several federal laws demand that insurers reimburse for mental health care on par with coverage for general medical care, but reimbursement often requires a diagnosis of a mental health disorder. Without a law like Delaware’s, mental health providers are financially disincentivized from screening children as part of routine care, or before they reach the level of a diagnosable disorder. The surgeon general’s advisory said the medical establishment must “recognize mental health as an essential part of overall health.” And so, affordable and accessible preventive mental health care is vital to improving youth mental health.

Delaware’s new law prioritizes early access to mental health screening and support. It will allow parents and health professionals to get ahead of concerns before they reach a crisis level. For many children with early-stage mental health concerns, short-term therapy can yield good results.

Studies show that universal mental health screenings in primary care improve detection rates for concerns like anxiety, depression, and suicidality and, in some cases, has even reduced racial health disparities.

The law also improves overall access to care by integrating mental health into the regular pediatrician’s annual visit. Parents often report difficulty with taking their children to multiple offices and appointments, citing issues like transportation, childcare, and getting time off work. They prefer to receive mental health care in their pediatrician’s office.

And then there’s the workforce shortage. Although the number of child psychiatrists in the U.S. increased over the past decade, there are still not enough to meet demand, especially in low-income and rural counties. Further, 14 million kids and teens lack access to a school-based mental health professional, such as a school psychologist, counselor, or social worker.

Delaware’s law will allow master-level practitioners in counseling and social work to provide the annual wellness screenings rather than requiring doctoral-level practitioners. Counselors and clinical social workers without doctorates can be trained three to four years more quickly than psychiatrists and psychologists with doctorates. Their training is well-suited for this early support role.

Finally, the Delaware law is more cost-effective than our current spending on mental health treatment and related hospitalizations – which reached $225 billion in 2019. Comparatively, making mental health part of standard primary care could save health insurers up to $68 billion every year.

Other states are experimenting with similar programs, although none have gone as far as Delaware. Ohio is piloting team-based well child visits where mental health specialists work together with pediatricians in the same visit. California announced statewide insurance coverage for well-child visits (including mental health) through their Medicaid program coming in 2023. Oregon lawmakers have proposed a plan to require insurers on the federal insurance marketplace to offer three free primary health care visits to patients each year, with both mental and physical health providers.

Still, with its new law, Delaware is burnishing a “first in the nation” status in mental health care. We can only hope more states follow in its footsteps.

Top illustration: SimpleHappyArt / iStock