Book

How to calm The Anxious Generation

When it comes to our young people and their mental health, the news is not good. Suicide is the second-leading cause of death for people under 24 in the U.S., and a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report last year found 20 percent of the country’s 12- to 17-year-olds had had at least one major depressive episode—results unlike anything the CDC had seen in thirty years of collecting such data. Its director of adolescent and school health, Kathlee Ethie, called the findings “devastating.” She said, “Young people are telling us they are in crisis. The data really call on us to act.”

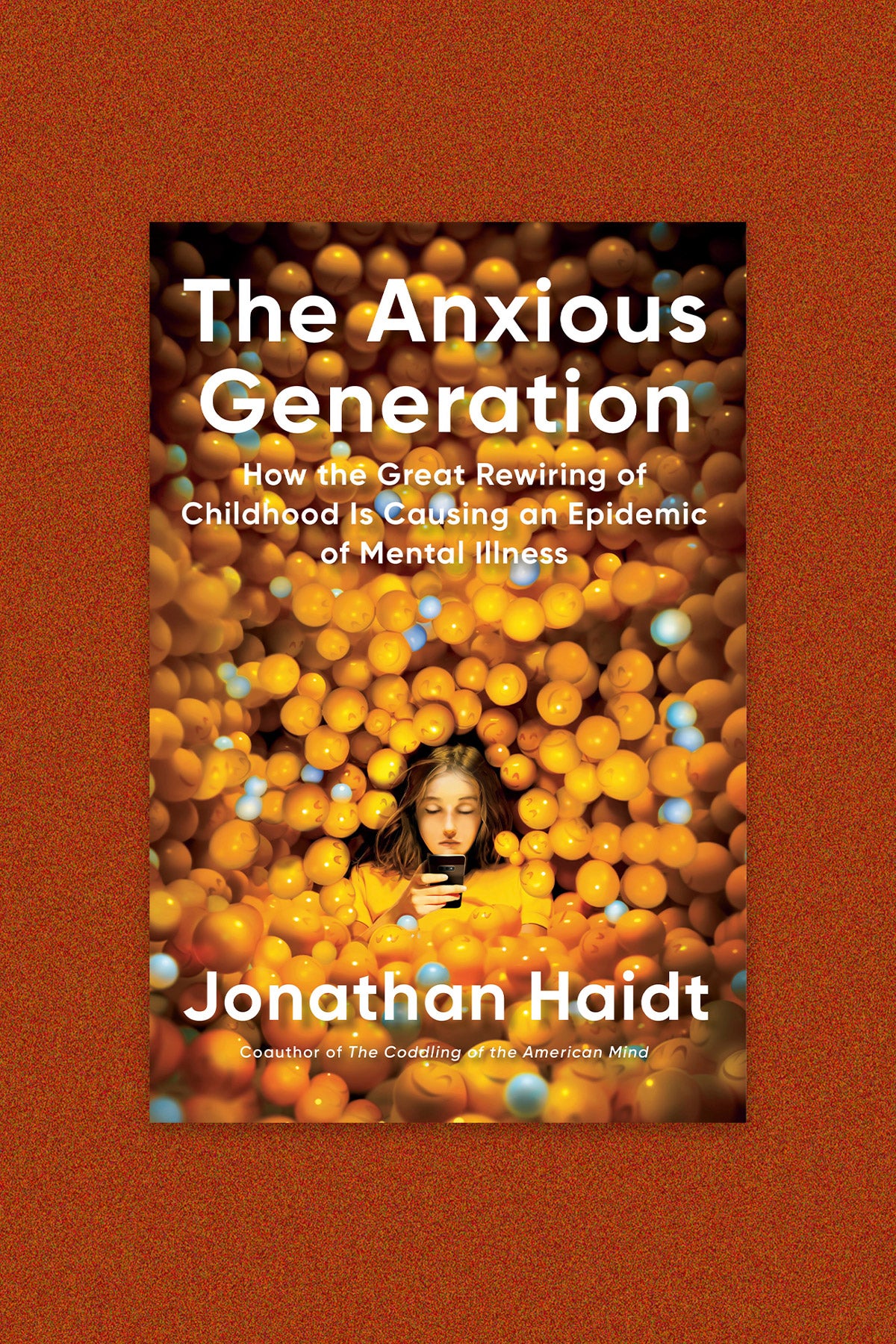

There are plenty of recommendations for action in Jonathan Haidt’s new book, The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. Haidt, a psychologist at New York University, starts by giving readers a baseline on kids, why girls have higher rates of mood disorders and self-harming behavior, and why today’s boys are more at risk of “failure to launch” (that is, transition from adolescence to adulthood). And—perhaps not surprising, from the author of The Coddling of the American Mind—he argues that parents are overprotecting their kids in the real, physical world and underprotecting them in the Wild West online.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Haidt makes a strong case that social media—as distinct from the internet at large—is severely harming young people. Rates of mood disorders among U.S. college undergraduates suddenly spiked in the early 2010s. The number of kids reporting depression and anxiety rose steadily every year of that decade, till rates were up 134 percent and 106 percent, respectively, by 2020. Similar statistics are being seen in countries around the world. It’s probably no accident that Apple introduced its first front-facing camera phone in summer of 2010, and Instagram, which worked only on smartphones at the time, launched later that year. After Facebook purchased Instagram, its user base exploded, from 10 million users at the end of 2011 to 90 million by early 2013. The result, Haidt says: “Gen Z became the first generation in history to go through puberty with a portal in their pockets that called them away from the people nearby and into an alternative universe that was exciting, addictive, unstable, and … unsuitable for children and adolescents.”

Few of us have healthy relationships with our phones, but kids are especially vulnerable. Their brains are still developing; they’re still learning impulse control and values. Haidt cites a range of studies that help to make his case. Half of all teens reported feeling “addicted” to their phones in a survey published in 2016, for instance, while three out of five parents felt their kids were addicted. A more recent Pew Research Center study found nearly 100 percent of American teens have a smartphone, and roughly half say they’re online “constantly.”

It’s that level of attachment that leads Haidt to say a computerized device doesn’t simply correlate with the youth mental health crisis; it drives it. In 2022, he testified before Congress that one to two hours a day of social media use isn’t associated with a decline in mental health—but three or four hours a day is. In his book, he also cites studies establishing a causal relationship between Facebook adoption and depression and anxiety—particularly for girls. (To help understand why that might be, consider that internal research for Instagram led to a report saying, “We make body image issues worse for one in three teen girls.”)

Haidt also rebuts the idea that social media helps kids who feel out of place or marginalized by connecting them to peer groups and social support. “Unlike the extensive evidence of harm found in correlational, longitudinal, and experimental studies, there is very little evidence showing benefits to adolescent mental health from long-term or heavy social media use,” he writes.

Parental “safetyism”—i.e., keeping children away from anything the least bit risky, especially unsupervised outdoor play, is also part of the problem, both for younger children and adolescents. “A healthy human childhood with a lot of autonomy,” he writes, “sets children’s brains to operate mostly in ‘discover mode,’ with a well-developed attachment system and an ability to handle the risks of daily life.”

As for what we can do, Haidt makes plenty of cogent suggestions. My favorite was probably to make schools phone-free. Haidt holds up Mountain Middle School, located in an area of Colorado with some of the highest teen suicide rates in the state, as an example. A new principal at the charter school saw students suffering from cyberbullying, excessive social comparison, and phone-related sleep deprivation; he banned phones at school. The effects were nearly instantaneous—and dramatic. Kids talked to each other more. They lived in the moment, rather than on their phones. Soon enough they also reported being happier and less stressed. The school, still phone-free, was subsequently awarded Colorado’s highest academic performance rating.

Haidt calls on all of us to ask local and federal government to implement changes such as raising the age of legal “internet adulthood” from 13 to 16. He offers sensible, easy suggestions for parents, starting with telling your child, “Do something new, on your own.” It can be something as simple as making a meal, climbing a tree, or taking the dog for a walk. You’ll see the results immediately, he says.

Haidt begins his book by saying we’d never pack our kids off to an unfamiliar planet where humans hadn’t lived before. And yet, he says our kids are basically living on another planet right here on Earth because they no longer grow up engaged in physical play, physically surrounded by other human beings and communities. He ends his book by saying, “Let’s bring our children home.” Let us indeed.

Book cover courtesy of Penguin Random House