Will Howard speaks about his child at a Sad Dads Club retreat in Raymond, Maine, in October. The Sad Dads Club is a nonprofit for fathers who have lost children.

Feature

“People forget about the fathers.”

Rob Reider outfitted the “man cave” in his basement with equipment to practice his hobbies: a Fender Telecaster and a drum set, from his years in punk bands, and a bench press, pull-up bar, and assorted free weights. He strung Christmas lights near the ceiling and named the room “The Tone Zone,” a sanctuary for building strength.

On a recent Monday night in Falmouth, Maine, Reider went to the room to work different muscles. He opened his MacBook and joined 50 men on a Zoom call. “Tonight’s topic is relationships after loss,” Reider, 39, announces.

With that, he’s kicked off the week’s meeting of The Sad Dads Club. It’s a support group he cofounded for men whose children have died. But it has grown so quickly, and built such deep bonds between its members, that the club is more like a congregation of the faithful in the barren world of men’s grief.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Losing a child is one of the most painful and rearranging events an adult can endure, experts say. No one tracks the exact number of parents living through that experience, but CDC estimates indicate 44,000 children aged 18 and under die annually, and 21,000 babies are stillborn. There’s no roadmap for life or healing afterward. Hospital clinicians often have little bereavement training or time to help. Private mental health counselors are in record demand.

The support services that do exist often focus on mothers. Seventy-five percent of parents in pediatric palliative care research are mothers, while fathers are an underserved population. “People sort of forget about the fathers,” says Katherine Shear, the founding director of the Center for Prolonged Grief at the Columbia University School of Social Work.

Yet grief needs a witness. Telling the story of what happened is crucial to eventual acceptance and to the ability to live with the absence of the person, says Shear. But for generations of American men, grief—with its stew of sadness, yearning and powerlessness—was something to bury, to mask with stoicism, or to avoid with work, even if it came at great cost to mental health.

Fathers attending the Sad Dads Club retreat in October place items they remember their children by on the mantle in the retreat house. Twice annually, two dozen or so “Sad Dads” gather at a cabin on Panther Pond, for the retreat.

That’s changing. Over half of Gen Z and millennials report they’ve been to therapy, and 90 percent believe more Americans should go. But fathers still tend to grieve in isolation. And their grief is different. Research shows the intensity of grief is higher for mothers immediately following the death of children; their PTSD diminishes over time, while for fathers, it persists.

All of these factors are exacerbated by the mental health care gap men generally experience. Depression-related suicide is a leading cause of death among men in the United States, where they are far less likely than women to seek help due to stigma and lack of access.

Enter DIY grief groups, like the one Reider leads from his home in fog-soaked Falmouth. Dozens of men of all manner of personalities and occupations dial in from outposts like Prescott Valley, Arizona; Boise, Idaho; Austin, Texas; Calgary, Alberta—even Paris, where it’s 2:30 a.m. when the group logs on.

The men introduce themselves with the names of their lost children. “I’m Mike, Avery’s dad,” says one father from Glen Burnie, Maryland. “Avery was stillborn due to placental abruption.” Mark, Patrick’s dad, explains how his two best friends recently had children, and it’s too painful for him to share in their joy. He feels like he’s losing these friends after losing his child. He wants to know: Has anyone else experienced this?

A Zoom hand raises. Parker’s dad, Spencer, knows this feeling. He told his friends he needed time. Two-and-a-half years later, it’s easier to celebrate their milestones. Grief gets more manageable, he says, and “that’s largely thanks to this group.” Others describe the stab they feel when there are pregnancy announcements at work, or invitations to baby showers. One dad says his own father is surprised that he’s still grieving.

Rob Reider

Christopher Piasecki

Jay Tansey

Rob Reider, Christopher Piasecki, and Jay Tansey cofounded the Sad Dads Club, a nonprofit bereavement organization for fathers. Reider is also its executive director.

No hierarchy

All three Sad Dads cofounders, who are in their 30s, say their experience with professional counseling was lifesaving. The group (now a nonprofit) fundraises to pay for six sessions with private therapists for its dads, at no cost.

Men’s support groups offer something more than direct help: a foxhole for shared, unfiltered experience. Kinship. Permission to be vulnerable.

Reider, the executive director of The Sad Dads Club nonprofit, has his daughter’s name, “LILA,” tattooed across the front of his neck. In 2017, Reider and his best friend, Jay Tansey, both lost children to stillbirth. Then it happened to Chris Piasecki, the husband of a college classmate. The three men met up at a bar in Portland, Maine, and bawled their eyes out. “When I sat down with Rob and Jay, it was the first time I could let go of all inhibitions,” says Piasecki. “I didn’t have to think, ‘Am I burdening them?’”

Especially for men, peer support has great potential to provide essential social connections, says Paul Sharp, senior lecturer at the School of Health Sciences at UNSW Sydney. One’s partner may not be the best buoy—they’re lost in their own despair. And navigating grief as a couple is also fraught: Researchers have found that when parents lose an infant, the greatest risk to their relationship comes from unequal or different grieving processes.

Piasecki wanted to support his wife first and remembers experiencing “delayed grief.” He remembers hopelessness: How do you help your spouse with something you don’t yet know how to manage? And he remembers guilt: How can your grief as a father compare to the grief of the woman who carried the child in her own body?

In a therapist’s office, men might perceive disclosing their challenges as giving up, admitting defeat, or creating a power imbalance, says Sharp. Men’s support groups, on the other hand, have no hierarchy. You can join a Zoom meeting with the camera off and listen for a year, or join a private channel on Discord, a messaging app, and post with 130 other dads. Fantasy football leagues emerge (there are five in The Sad Dads Club). Men share reading recommendations, hiking paths—contours of a new life.

Kyle McBrien plays the guitar while Eugene Daneshvar rests on the couch in the house where the Sad Dads Club retreat was held in Raymond, Maine.

Chris Piasecki, a cofounder of the Sad Dads Club, passes a cup to one of the fathers attending the group’s retreat.

Michael MacDonald (left) speaks with Jay Tansey (right) during the weekend-long retreat.

Albert Thomas hugs another father at the Sad Dads Club retreat.

For Terry Mayfield, 43, relationships were forced to endure tectonic rearrangement after the death of his infant son. Initially, merely being awake was intolerable. He felt his whole family was just waiting for him to “get better.” Meanwhile, neighbors he barely knew—those who could sit with his sorrow—became central in his new life. He longed for camaraderie and found comfort in people for whom “life didn’t go the way they expected.”

Mayfield sought counseling and a coed grief group. But he didn’t feel comfortable expressing the depth of his sadness until he attended a grief group for fathers sponsored by Full Circle Grief Center in Richmond, Virginia. Dads there spoke of honoring their children and of making meaning from the life still ahead of them (a key grief step, says Columbia University’s Shear). Mayfield soon began coaching the Special Olympics.

For Black men—like Mayfield and his father—vulnerability is especially hard, says Henry Willis, assistant professor of psychology at the University of Maryland. Some men may have learned early on to guard their emotions as protection against racism and discrimination. To struggle with grief for a long time carries a stigma.

“To see a future version of myself”

Grief is permanent, says Shear, but that doesn’t mean suffering is. Grief is the way we experience loss in the moment; it shifts over a lifetime. Willis says support groups can be beneficial if they offer an environment for processing emotion, and for thinking about a new identity.

These needs show up differently at each meeting of the Sad Dads. Like that recent night Reider led a meeting from Maine, where dozens of virtual hands raise. “I felt like I was carrying around this unbearable pain, and the only thing I wanted to do was put it down for a while and rest,” one dad says.

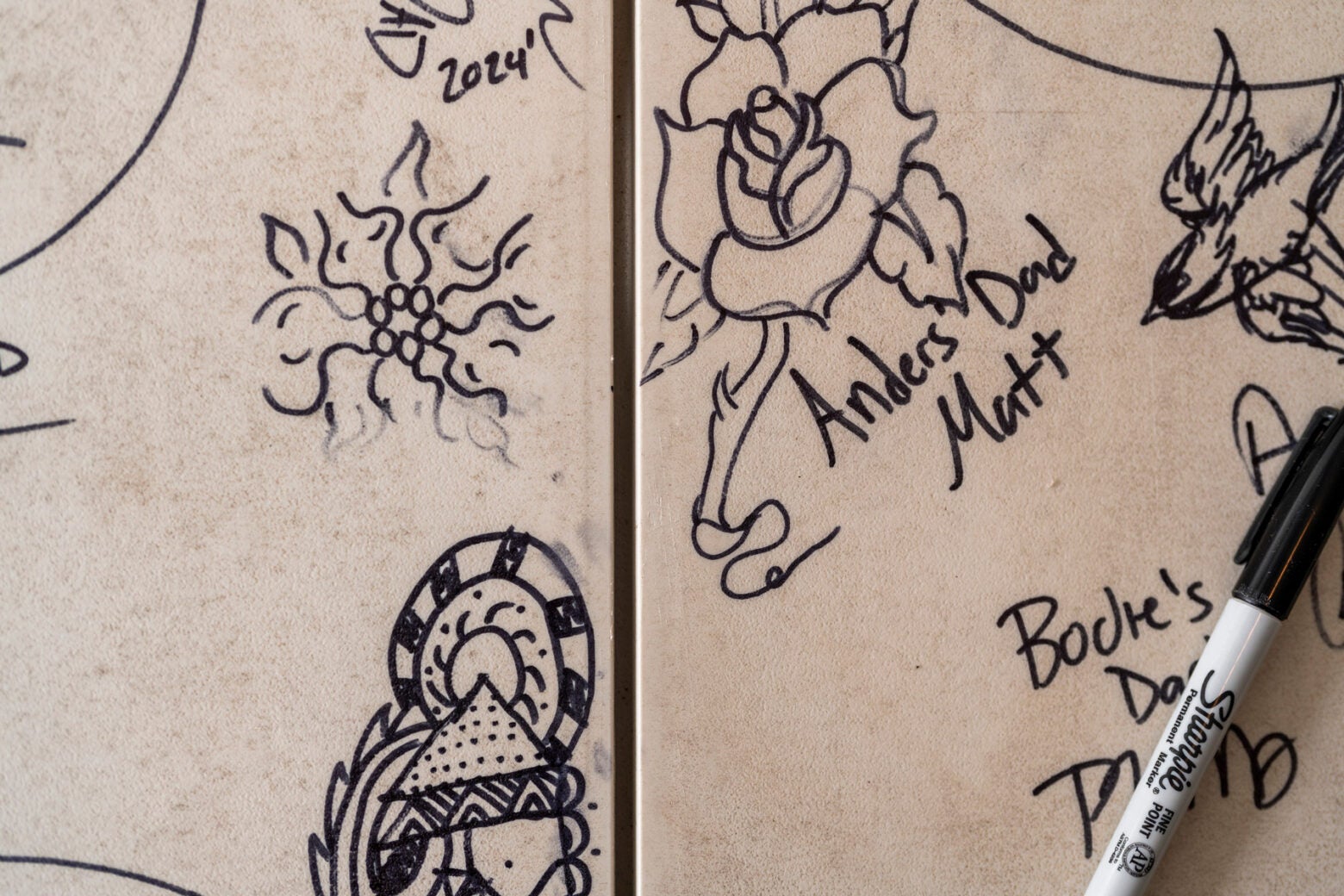

Fathers attending the Sad Dads Club retreat sign their names and those of their late children on a folding table in the garage of the cabin where they stay.

It’s “non-negotiable to say I only have one child,” says another dad. “I have to acknowledge my daughter,” he says, meaning the one who died.

“I’ve been waiting for her to . . . feel a little bit better, to take more of life in,” says a third dad of his wife. Their relationship roots his life; when she feels better, he will too, he suggests. On alternate Thursdays, one dad tells the story of his loss to the entire group; those sessions are already booked through this time next year.

Seven years after his daughter’s death, Reider’s optimism is real. He no longer associates Lila with only sadness. There’s good in life; transformation. Hospital bereavement packets across the country now list The Sad Dads Club as a resource. He has completed a facilitator training course to become a better listener.

Two fathers in the Sad Dads Club visit Panther Pond during the group’s weekend retreat in October.

“You are never going to make progress or help yourself feel better if you don’t face it,” he says, citing vulnerability as “the ultimate form of strength.”

Twice annually, about two dozen of the Sad Dads migrate to a cabin on Panther Pond, northwest of Portland, to kayak, cook pancakes, drink beer, and line the mantle with their children’s mementos—knit hospital caps, stuffed bears. It’s okay for them to have fun. They make friends and plans. They hashtag #worstclubbestguys. Sustained by each other, they live their absences.

Once, when some dads on the Zoom were smiling and laughing, the founders thought to announce that the group is serious, dedicated to the gravity and complexity of loss. No, said another dad—keep laughing. “I came here to see a future version of myself.”