Feature

Seeing industrial pollution through a journalist’s lens

This article was originally published by The GroundTruth Project.

The pollutants produced by extractive industries are often measured in parts per billion. That’s not something you can photograph directly, and not a data set that is a gripping narrative in itself—but the impact is tangible, devastating communities and wildlife across the world.

Photographing and writing for Report for America newsroom PublicSource in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, [Report for America] corps member Quinn Glabicki is often tasked with representing the invisible chemicals’ impact on his community. And as Glabicki said, “There’s only so many pictures of smokestacks you can take.”

Brandon Sample (left) and Luke Zidek (right) conduct a hazmat training exercise in Duquesne, Pennsylvania, in 2023 as part of Auberle’s brownfield redevelopment training program.

Quinn Glabicki / PublicSource

Here, Glabicki sells himself a bit short—his pictures of smokestacks are intensely dialed in. Every line and shadow is carefully considered, giving each composition either exquisite balance or an equally well-rendered imbalance. But the real heart of his work is the care and intimacy with which he photographs the people most affected by industrial pollution.

“I grew up in Pittsburgh, and my grandpa told me stories about living on the South Side in the fifties, walking home and his white shirt had turned black from all the soot in the air,” Glabicki said. “And I think in a lot of ways it’s romanticized—like there’s this quintessential smokestack picture that’s been the same picture for 150 years.”

It is a picture that has long been a stand-in for the concept of honorable, patriotic, dirty, dangerous work—and is now also synonymous with forever chemicals and cancer clusters.

“I try to make portraits of people in places they feel a connection to, to give a little bit of sense of place and how that person interacts with their environment,” Glabicki said. “Even if it’s somewhere their great-grandfather worked 70 years ago. Or photographing Edith in this field totally taken over by bittersweet, for a story about how industry is encroaching on these communities and kind of taking over their lives and their identities.”

Young Bears emerge from beneath the bleachers to take the field for a Saturday Little League game in 2021 in Clairton, Pennsylvania. Clairton has some of the worst chronic air pollution in the United States and is home to U.S. Steel’s Clairton Coke Works, the largest coking facility in North America.

Quinn Glabicki / PublicSource

The Clairton marching band marches along Miller Avenue toward the football stadium and the first home game of the 2021 season.

Quinn Glabicki / PublicSource

Balancing writing and photography, Glabicki said he will often begin his interactions with his subjects as a writer, asking questions and hanging out. Once people are more comfortable with him being around, he’ll bring out his cameras. He favors small, unobtrusive mirrorless cameras—primarily Leica and Canon.

“A lot of the time I’m sitting with somebody talking to them about pretty heavy stuff for hours—I want to be as present as I can in the conversation and not running around photographing them,” Glabicki said. “But it’s in those little tiny moments in interviews, they don’t forget you’re there, but it’s almost like they’re okay with you photographing a little bit of their vulnerability. I don’t want to say they perform, but they understand how what they’re doing will be understood by readers seeing it.”

Tom Bussoletti looks out over a site near his home where a new pipeline is being built through the forest near New Freeport, in Greene County, Pennsylvania.

Quinn Glabicki / PublicSource

As an internationally-experienced photographer who picked up writing as a way to get more assignments and exert more control over his finished pieces, Glabicki has developed a style through his editors’ mentorship and reading literary journalism.

“I love the way that magazine articles are able to have the space to weave multiple characters together, to zoom really far in and then zoom really far out,” Glabicki said. “I try to take a reader on multiple stops around an issue or around a family and what they’ve gone through or around a community and what they’re dealing with. It’s like each scene kind of builds a different understanding of the issue. So by the time that you get to the end of it, you have more of a nuanced understanding of what’s going on and the people involved.”

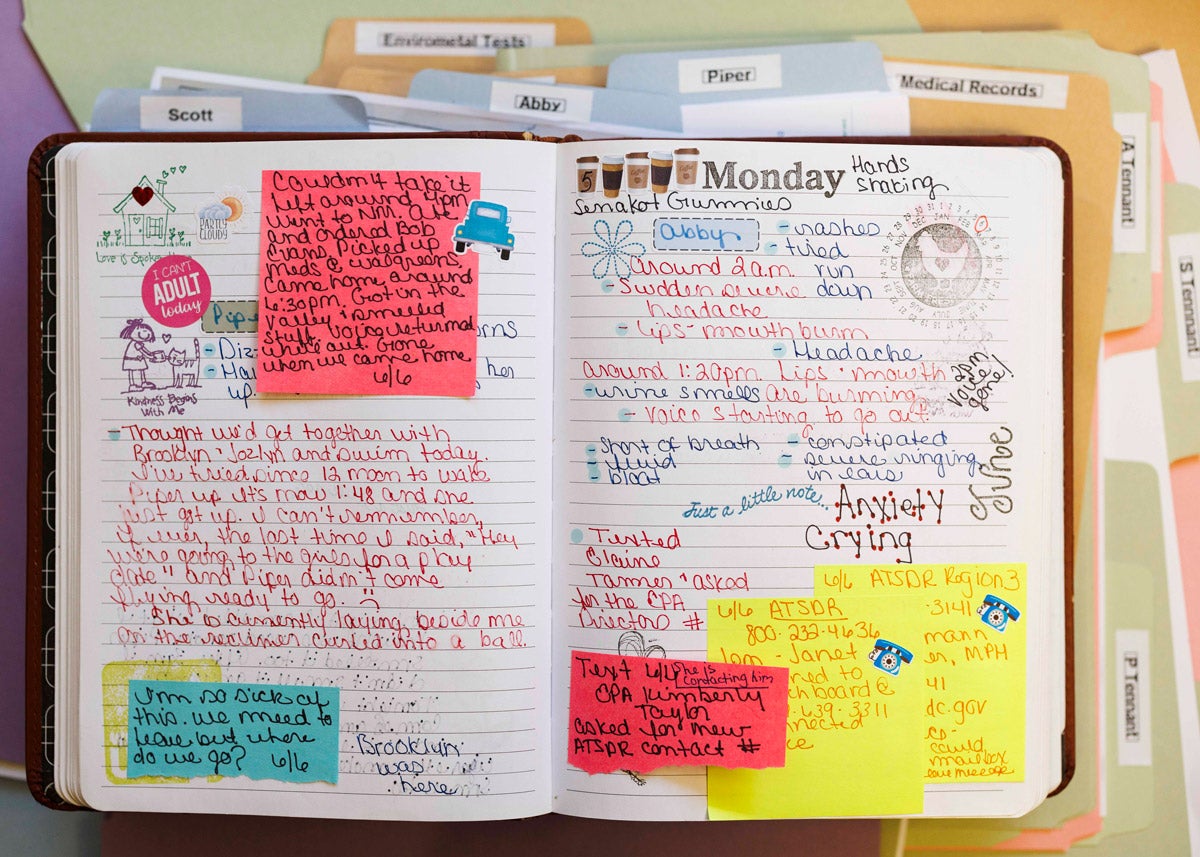

His investigation for PublicSource chronicles gas corporation EQT’s fracking expansion and the communities devastated by their operations. In reporting out the story, he discovered an artifact to help bridge the gulf between image and text: Abby Tennant’s handwritten journal chronicling her acute health issues from living in EQT’s frack path.

Scott and Abby Tennant embrace at the home in Baden City, West Virginia, where the couple and their daughter relocated after the family was sickened by EQT fracking operations near their home.

Quinn Glabicki / PublicSource

Using stickers as a coda to her daily activities, Tennant details fleeing a cloud of noxious fumes in the middle of the night. Glabicki was allowed to photograph these diaries, and did so in a straightforward, legible way, but also included the Tennant family’s medical files in the background, to situate the ravages of parts per billion in human terms.

Abby Tennant’s journals document her family’s illnesses and displacement after EQT fracking operations expanded in the hollow where they lived in Knob Fork, West Virginia.

Quinn Glabicki / PublicSource

“[Abby] gave me three notebooks—I opened one and it was just stuffed with Post-it notes,” Glabicki said. So much of that story was about chaos, and this frantic way that she’s documenting every day in a very intentional way. I tried to photograph them in a way that they could be read, but with the background of all of her documents, to give them some agency. She was not a passive victim of what was happening to them—she was doing all that she could. It was important to highlight that. But also highlight that it was falling on deaf ears.”