Opinion

At COP28, health should be as important as carbon emissions

This week, world leaders are gathering again for the annual United Nations climate conference: COP28, this time in Dubai. It’s a landmark moment for public health, which is part of the summit agenda for the first time in nearly 30 years. And not a moment too soon: Climate change is the greatest threat to global public health, and one that deepens existing inequities.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

This year also marks the first-ever global “stocktake”—a review of progress toward the goals of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. For public health professionals, this can be a strategic moment. As global leaders and governments deliberate action at COP28 and beyond, they must prioritize climate solutions that place health equity front and center. Doing so will save lives and safeguard the future of the planet.

Take the transportation sector, for example, which is currently the world’s largest source of emissions and a major contributor to air pollution. “Green” transportation policies often focus on transitioning from gas to electric cars. But we need to transition away from the status quo entirely. A transportation system that prioritizes both our health and the climate would include biking and walking (the healthiest ways to travel) and clean, safe, accessible public transportation that can accommodate the needs of people who cannot drive, walk, or bike. Doing so would mean we benefit from clean air and reduced CO2 emissions—and from a less sedentary lifestyle, decreased risk of motor vehicle accidents, and less pollution from car tires.

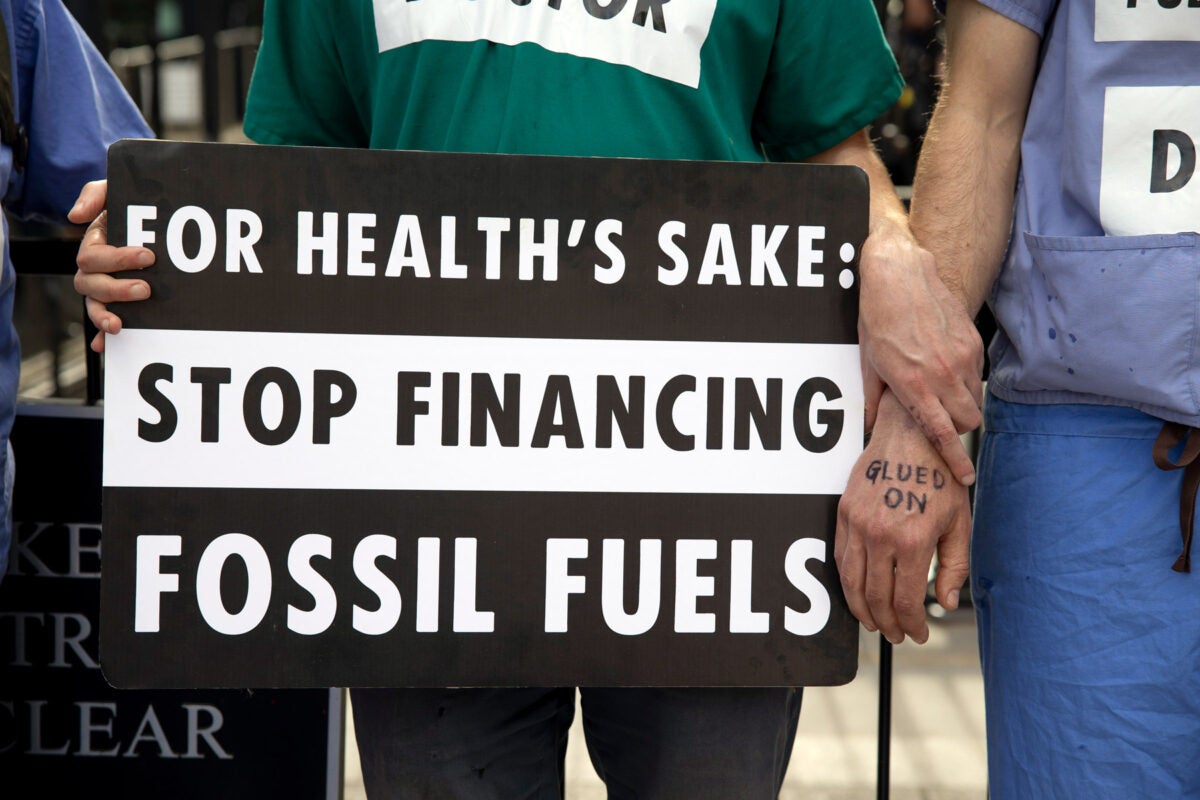

Energy is another example. Phasing out fossil fuels is urgent, but solutions like carbon capture and energy storage are a false promise. They may reduce emissions, but they ultimately prolong our dependence on fossil fuels. Continued reliance on so-called “climate-friendly” fossil fuels means that babies born next to oil and gas drilling sites will still be at risk for heart defects at birth; that coal miners will struggle to breathe as they suffer from black lung; and that millions will continue to experience the health risks of air and water polluted by fossil fuels. A health equity lens helps us see that the harms of fossil fuels are many, and they threaten both human and environmental health.

Lastly, labor. Workers in construction and agriculture, for example, are exposed to increased risk of heat stroke, respiratory issues, and cardiac complications as outdoor temperatures rise around the globe. Limiting climate damage, and thus extreme heat, will protect workers from these health risks—and mitigate productivity losses, to boot. (In 2022 alone, the U.S. experienced severe productivity losses, up to $81 billion by some estimates, with the construction industry carrying nearly half of those losses.)

When policymakers consider climate change policy through a health equity lens, they develop more holistic solutions like improving urban green spaces in historically redlined neighborhoods, increasing clean air conditioning access for low-income families, and supporting better workplace protections for outdoor workers. That’s good for all of us.

The lived experience of billions of people who are facing the reality of the climate crisis makes it clear that we need to get to zero emissions as soon as possible. How we get there is just as crucial. So, whether it’s city governments greening neighborhoods, state departments of transportation improving walkability, or labor unions protecting workers from extreme heat, centering health equity at COP28 and beyond will promote our health and the health of our planet.

Image: Hesther Ng / SOPA Images/ Sipa USA via AP Images