People

“A healthy environment supports healthy people.”

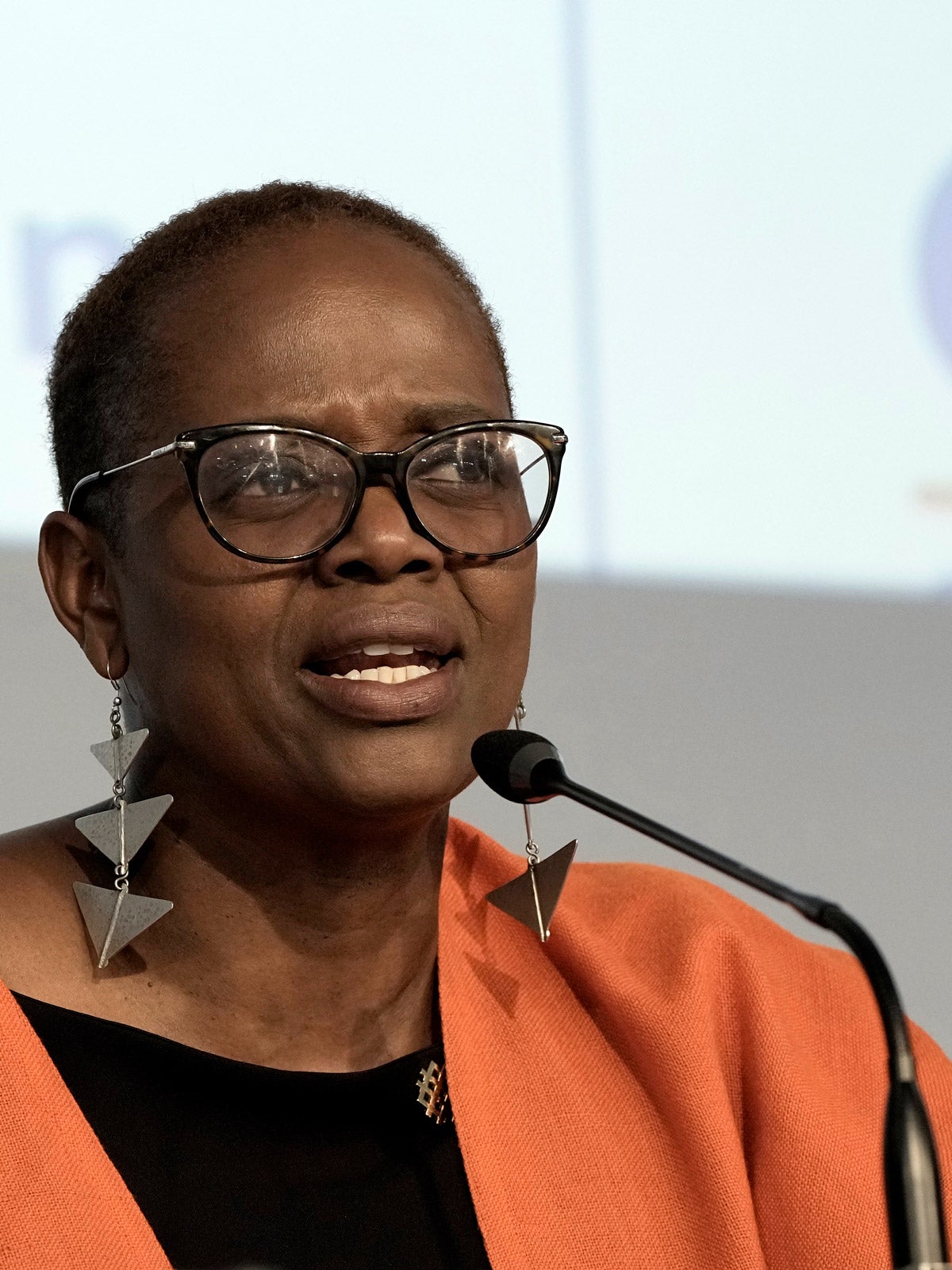

Wanjira Mathai was just six years old when her mother, Wangari Maathai, founded the Green Belt Movement, a grassroots effort to fight deforestation through planting trees. Nearly 30 years later, Maathai was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for that work, and her daughter had become a respected environmentalist and leader in her own right. After earning master’s degrees in public health and business at Emory University, Wanjira Mathai joined the Carter Center, working on disease control, and then returned to Kenya to become the Green Belt Movement’s director of international affairs and, later, its executive director. (She remains on its board of directors). Today, Mathai helps lead the World Resources Institute as its managing director of Africa and global partnerships. She continues to help African countries make environmental restoration decisions that also improve local economies. She spoke with Leah Samuel for Harvard Public Health.

HPH: What is your public health perspective on climate change?

Mathai: At the Carter Center, the diseases I worked on eradicating, like Guinea-worm disease and river blindness, were about polluted water. The water was harboring vectors like mosquitos, breeding in rivers and carrying disease. And with flooding comes infectious diseases like cholera, especially in urban areas. People get infected very quickly. And when people can’t get clean water to drink, health is affected immediately.

Climate change has essentially exacerbated all of that. And land use change, urbanization, and growth has also resulted in a lot more degradation.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

HPH: Regions of Kenya, where your mom started the Greenbelt Movement, were among the earliest places where environmental degradation directly affected public health. What has that looked like over the years?

Mathai: There’s been so much land use change, especially in ecosystems of importance for water. When it rains, the water is supposed to very gently come down the trunks of the trees and soak into the underground aquifers—and release to us as rivers. That’s the classic water cycle.

Now, a lot more land is paved; a lot more land is degraded. Trees have been removed, replaced with crops. That rainwater now is rushing, running off before it ever has a chance to seep into the underground aquifers. That creates flooding and, of course, disease, displacement, and loss of lives and livelihoods.

That’s why it is so important to restore as much as we can. Let’s create buffer zones along rivers. And let’s plant bamboo along those rivers. Bamboo is known as a sponge. It allows water to slow down and go under the ground.

HPH: You’ve said that if we do not address poverty, climate change will be worse. Why is it important to work on both?

Mathai: Poverty is the chief driver of vulnerability. If people are living on the edge of the edge, they are living precariously in such poverty that any small shock will push them over. It’s very difficult for them to adapt and build the sort of resilience that’s needed to survive climate shocks.

Some countries invest a lot in saving lives during climate events like floods. But when the people come back, their livelihoods are gone. Businesses have been washed away. The same communities working to restore their landscapes are also working to secure their food supplies and water supplies.

All of that is a function of a healthier environment as well. We have got to address poverty as part of the resilience-building. We have got to transform people’s lives and livelihoods as part of addressing climate.

HPH: Are governments are vulnerable as well? How does poverty affect them?

Mathai: As climate events are getting worse, many countries cannot adapt amidst abject poverty. The International Panel on Climate Change had a fascinating example in their report. Bangladesh and the Netherlands are not so different in terms of their exposure to climate-related risks like flooding. In fact, the Netherlands is lower in sea level, right? You would think the Netherlands would suffer more. But when there is a flood in the Netherlands, they’re able to change. They can use technology tools for early warning systems. They can build dikes, higher bridges, and other adaptive infrastructure. They’re able to prevent water from flooding their cities. They’re able to save lives.

In Bangladesh every typhoon, every flood event, would kill thousands of people. Bangladesh was more vulnerable, purely based on economic prosperity. Countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan, and many countries in Africa are hard pressed to invest their own resources in adaptation. It competes for funds with development. And what do they choose to pay for? Schools or bridges? What’s the choice?

HPH: So, how do you sell poorer countries on environmental restoration?

Mathai: We’ve taken three major landscapes across Africa to demonstrate that there is a restoration economy to be had, especially for young people. You can have people involved in agroforestry, ensuring that there are trees on farms. Those trees could be fruit trees. Three women who started a macadamia business are incentivizing farmers to put macadamia nut trees on their farms because they are the most prized nut in the world. There’s a wonderful young man who’s growing acacia trees and harvesting gum arabica from them for the cosmetic and beverage industries.

The restoration potential in Africa is the greatest in the world. Seven hundred million hectares (1.73 billion acres) need to be restored. The youngest workforce in the world is on our continent. The role of nature-based solutions to unemployment is huge.

Putting trees on landscapes can be income generating.

HPH: So for you, these two are really intertwined—environment and public health.

Mathai: Moving from public health practice to environmental work, I realized how similar they are. I really came to appreciate the intersection. It just seemed so relevant and important that we would be concerned about the general health of communities rather than the health of individuals. A healthy environment supports healthy people.

Image: Nariman El-Mofty / AP Photo

Republish this article

<p>Wanjira Mathai unpacks connections between climate change and public health.</p>

<p>Written by Leah Samuel</p>

<p>This <a rel="canonical" href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/environmental-health/a-qa-with-wanjira-mathai-of-the-world-resources-institute/">article</a> originally appeared in<a href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/">Harvard Public Health magazine</a>. Subscribe to their <a href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/subscribe/">newsletter</a>.</p>

<p class="has-drop-cap">Wanjira Mathai was just six years old when her mother, Wangari Maathai, founded the Green Belt Movement, a grassroots effort to fight deforestation through planting trees. Nearly 30 years later, Maathai was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for that work, and her daughter had become a respected environmentalist and leader in her own right. After earning master’s degrees in public health and business at Emory University, Wanjira Mathai joined the Carter Center, working on disease control, and then returned to Kenya to become the <a href="https://www.greenbeltmovement.org/" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">Green Belt Movement</a>’s director of international affairs and, later, its executive director. (She remains on its board of directors). Today, Mathai helps lead the <a href="https://www.wri.org/" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">World Resources Institute</a> as its managing director of Africa and global partnerships. She continues to help African countries make environmental restoration decisions that also improve local economies. She spoke with Leah Samuel for <em>Harvard Public Health.</em></p>

<p><strong>HPH: </strong>What is your public health perspective on climate change?</p>

<p><strong>Mathai:</strong> At the Carter Center, the diseases I worked on eradicating, like Guinea-worm disease and river blindness, were about polluted water. The water was harboring vectors like mosquitos, breeding in rivers and carrying disease. And with flooding comes infectious diseases like cholera, especially in urban areas. People get infected very quickly. And when people can't get clean water to drink, health is affected immediately.</p>

<p>Climate change has essentially exacerbated all of that. And land use change, urbanization, and growth has also resulted in a lot more degradation.</p>

<p><strong>HPH: </strong>Regions of Kenya, where your mom started the Greenbelt Movement, were among the earliest places where environmental degradation directly affected public health. What has that looked like over the years?</p>

<p><strong>Mathai:</strong> There's been so much land use change, especially in ecosystems of importance for water. When it rains, the water is supposed to very gently come down the trunks of the trees and soak into the underground aquifers—and release to us as rivers. That’s the classic water cycle.</p>

<p>Now, a lot more land is paved; a lot more land is degraded. Trees have been removed, replaced with crops. That rainwater now is rushing, running off before it ever has a chance to seep into the underground aquifers. That creates flooding and, of course, disease, displacement, and loss of lives and livelihoods.</p>

<p>That’s why it is so important to restore as much as we can. Let's create buffer zones along rivers. And let's plant bamboo along those rivers. Bamboo is known as a sponge. It allows water to slow down and go under the ground.</p>

<p><strong>HPH: </strong>You’ve said that if we do not address poverty, climate change will be worse. Why is it important to work on both?</p>

<p><strong>Mathai:</strong> Poverty is the chief driver of vulnerability. If people are living on the edge of the edge, they are living precariously in such poverty that any small shock will push them over. It's very difficult for them to adapt and build the sort of resilience that's needed to survive climate shocks.</p>

<p>Some countries invest a lot in saving lives during climate events like floods. But when the people come back, their livelihoods are gone. Businesses have been washed away. The same communities working to restore their landscapes are also working to secure their food supplies and water supplies.</p>

<p>All of that is a function of a <a href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/environmental-health/" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">healthier environment</a> as well. We have got to address poverty as part of the resilience-building. We have got to transform people's lives and livelihoods as part of addressing climate.</p>

<p><strong>HPH:</strong> Are governments are vulnerable as well? How does poverty affect them?</p>

<p><strong>Mathai:</strong> As climate events are getting worse, many countries cannot adapt amidst abject poverty. The International Panel on Climate Change had a fascinating example in their report. Bangladesh and the Netherlands are not so different in terms of their exposure to climate-related risks like flooding. In fact, the Netherlands is lower in sea level, right? You would think the Netherlands would suffer more. But when there is a flood in the Netherlands, they're able to change. They can use technology tools for early warning systems. They can build dikes, higher bridges, and other adaptive infrastructure. They're able to prevent water from flooding their cities. They're able to save lives.</p>

<p>In Bangladesh every typhoon, every flood event, would kill thousands of people. Bangladesh was more vulnerable, purely based on economic prosperity. Countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan, and many countries in Africa are hard pressed to invest their own resources in adaptation. It competes for funds with development. And what do they choose to pay for? Schools or bridges? What's the choice?</p>

<p><strong>HPH: </strong>So, how do you sell poorer countries on environmental restoration?</p>

<p><strong>Mathai: </strong>We've taken three major landscapes across Africa to demonstrate that there is a restoration economy to be had, especially for young people. You can have people involved in agroforestry, ensuring that there are trees on farms. Those trees could be fruit trees. Three women who started a macadamia business are incentivizing farmers to put macadamia nut trees on their farms because they are the most prized nut in the world. There's a wonderful young man who's growing acacia trees and harvesting gum arabica from them for the cosmetic and beverage industries.</p>

<p>The restoration potential in Africa is the greatest in the world. Seven hundred million hectares (1.73 billion acres) need to be restored. The youngest workforce in the world is on our continent. The role of nature-based solutions to unemployment is huge.</p>

<p>Putting trees on landscapes can be income generating.</p>

<p><strong>HPH:</strong> So for you, these two are really intertwined—environment and public health.</p>

<p class=" t-has-endmark t-has-endmark"><strong>Mathai:</strong> Moving from public health practice to environmental work, I realized how similar they are. I really came to appreciate the intersection. It just seemed so relevant and important that we would be concerned about the general health of communities rather than the health of individuals. A healthy environment supports healthy people.</p>

<script async src="https://www.googletagmanager.com/gtag/js?id=G-S1L5BS4DJN"></script>

<script>

window.dataLayer = window.dataLayer || [];

if (typeof gtag !== "function") {function gtag(){dataLayer.push(arguments);}}

gtag('js', new Date());

gtag('config', 'G-S1L5BS4DJN');

</script>

Republishing guidelines

We’re happy to know you’re interested in republishing one of our stories. Please follow the guidelines below, adapted from other sites, primarily ProPublica’s Steal Our Stories guidelines (we didn’t steal all of its republishing guidelines, but we stole a lot of them). We also borrowed from Undark and KFF Health News.

Timeframe: Most stories and opinion pieces on our site can be republished within 90 days of posting. An article is available for republishing if our “Republish” button appears next to the story. We follow the Creative Commons noncommercial no-derivatives license.

When republishing a Harvard Public Health story, please follow these rules and use the required acknowledgments:

- Do not edit our stories, except to reflect changes in time (for instance, “last week” may replace “yesterday”), make style updates (we use serial commas; you may choose not to), and location (we spell out state names; you may choose not to).

- Include the author’s byline.

- Include text at the top of the story that says, “This article was originally published by Harvard Public Health. You must link the words “Harvard Public Health” to the story’s original/canonical URL.

- You must preserve the links in our stories, including our newsletter sign-up language and link.

- You must use our analytics tag: a single pixel and a snippet of HTML code that allows us to monitor our story’s traffic on your site. If you utilize our “Republish” link, the code will be automatically appended at the end of the article. It occupies minimal space and will be enclosed within a standard <script> tag.

- You must set the canonical link to the original Harvard Public Health URL or otherwise ensure that canonical tags are properly implemented to indicate that HPH is the original source of the content. For more information about canonical metadata, click here.

Packaging: Feel free to use our headline and deck or to craft your own headlines, subheads, and other material.

Art: You may republish editorial cartoons and photographs on stories with the “Republish” button. For illustrations or articles without the “Republish” button, please reach out to republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.

Exceptions: Stories that do not include a Republish button are either exclusive to us or governed by another collaborative agreement. Please reach out directly to the author, photographer, illustrator, or other named contributor for permission to reprint work that does not include our Republish button. Please do the same for stories published more than 90 days previously. If you have any questions, contact us at republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.

Translations: If you would like to translate our story into another language, please contact us first at republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.

Ads: It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads, but not ads specifically sold against our stories. You can’t state or imply that donations to your organization support Harvard Public Health.

Responsibilities and restrictions: You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third-party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. Harvard Public Health recognizes that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties aggregate or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

You may not republish our material wholesale or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You may not use our work to populate a website designed to improve rankings on search engines or solely to gain revenue from network-based advertisements.

Any website on which our stories appear must include a prominent and effective way to contact the editorial team at the publication.

Social media: If your publication shares republished stories on social media, we welcome a tag. We are @PublicHealthMag on X, Threads, and Instagram, and Harvard Public Health magazine on Facebook and LinkedIn.

Questions: If you have other questions, email us at republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.