Opinion

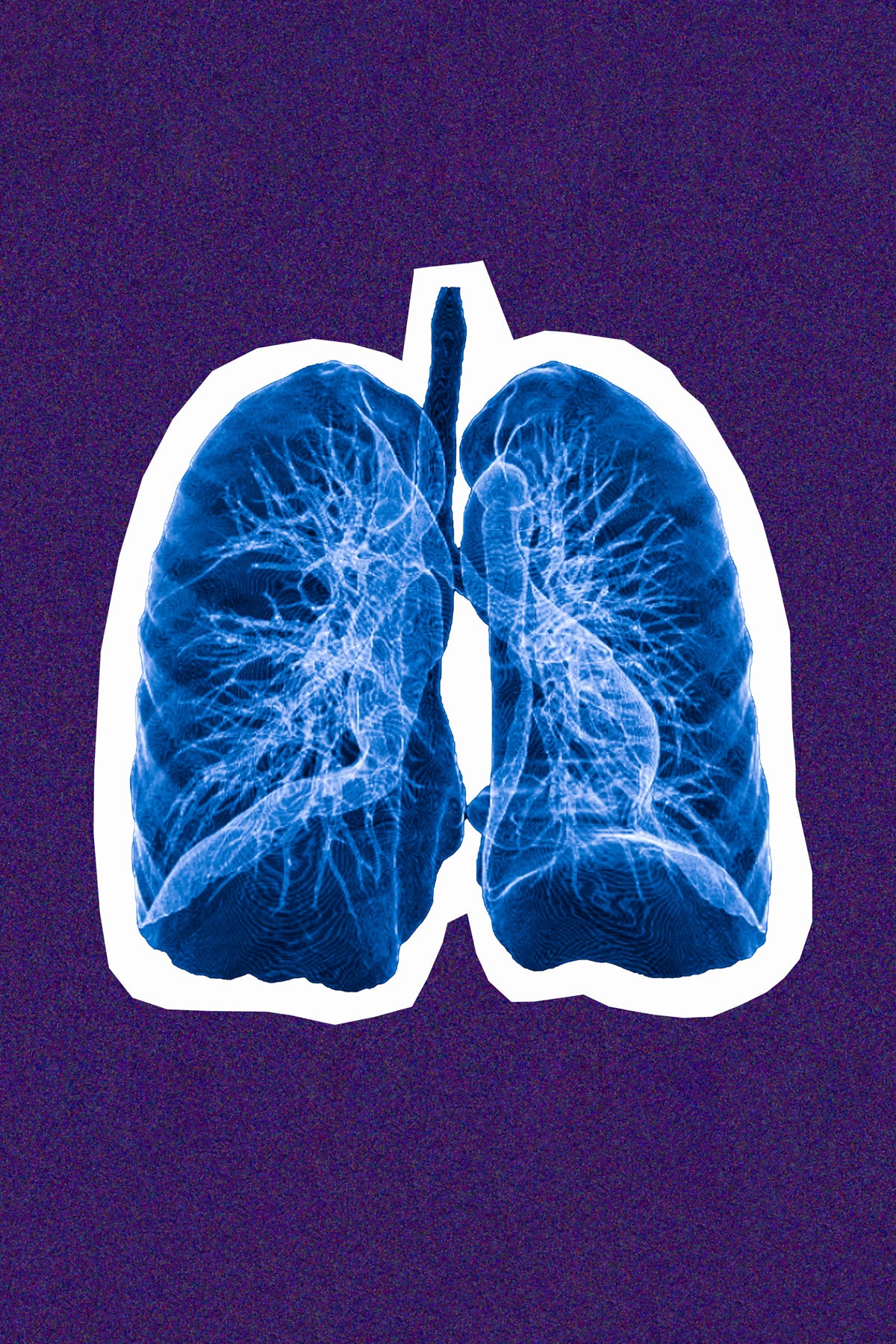

Lung cancer kills 130,000 Americans a year—but screening is rare

Thirty years ago, doctors had few options to treat patients with lung cancer, just chemotherapy and morphine to manage pain. In 1990, the five-year survival rate was 13.8%. Lung cancer is still the most lethal cancer in both men and women, but treatment advances mean lung cancer is no longer a death sentence. Today, the five-year survival rate for lung cancer is 22.9%, and 55% for patients who are diagnosed early.

With more than 50 therapeutic options for lung cancer patients, treatments are now tailored to individuals, and patients are living longer and better with the disease. Yet, despite this incredible progress, the tool that could save the most lives— screening—is hardly being used. Fewer than 6% of Americans at risk for developing lung cancer get screened annually. In contrast, more than 66% of eligible people are screened for breast cancer every year, and 69% for colorectal cancer.

As November marks Lung Cancer Awareness Month, we must talk about why the lung cancer screening rate remains so low, and how we can fix it.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guidelines recommend annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) for a subset of adults. To qualify, a person must be 50 to 80 years old, have a 20 “pack-year” smoking history (a pack a day for 20 years, two packs a day for 10 years, or another equivalent), and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years. The latest guidelines issued in 2021 expanded eligibility to an estimated 14.5 million people in the U.S.

A recent study showed screening the entire eligible population would save the lives of an estimated 23,444 people diagnosed with lung cancer each year.

So why don’t health providers screen more people? The main reason appears to be that most providers and patients don’t know annual lung cancer screening is available or recommended. The USPSTF only began recommending screening in 2013. Other types of routine cancer screening have been around much longer. The medical community took longer to adopt screening because they were not convinced of its benefits. Doctors worried about false positives, encouraging unnecessary testing, and treating harmless lung nodules. And of course, for a long time, treatment options for the disease were limited, and the prognosis poor. So lung cancer screening remained marginal compared to other types of cancer screening.

Another factor is stigma around cigarette smoking. To be eligible, patients must have a smoking history and patients often do not feel comfortable reporting theirs accurately. Public health efforts to reduce smoking succeeded in stigmatizing tobacco use, reducing widespread use, but also making it more difficult for health providers to work with patients who do smoke. Experts have debated whether the aggressive tactics used to stigmatize tobacco use have made it harder to treat lung cancer.

Many healthcare providers are also unfamiliar with the eligibility criteria and insurance coverage for screening, as opposed to other types of cancers. High-risk and low-income patients may not have access to insurance to pay for screenings, and until this year, only private insurers were required to cover annual screenings. In February, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid announced expansion of coverage for lung cancer screening to “improve health outcomes for people with lung cancer.”

Another challenge for early detection is restrictive screening guidelines. Nearly 25% of people diagnosed with lung cancer don’t qualify for annual screening because of age or lack of smoking history. Black men are the most likely of any group to develop and die of lung cancer, but Black women, Hispanic Americans, and women all face significant disparities in eligibility for screening.

To start, we must do a better job of engaging at-risk groups and raising awareness among those eligible for screening. Most importantly, we must start communicating that a lung cancer diagnosis is no longer a death sentence. If caught early enough, there are now advanced treatments helping patients live fuller, longer lives.

Expanding eligibility would also save lives, but we still need to ensure people have access to screening. We must also invest in early detection technology that can catch lung cancer early in people who do not meet current LDCT screening criteria.

While we continue to work towards early detection methods that are easier, more reliable, and less expensive to apply to a broader population, we must commit to raising screening rates for the eligible now. All eligible individuals must have the opportunity to make an informed decision about being screened. It just might save their lives.

President Biden said in a recent speech that getting more Americans screened and addressing barriers to screening is vital to our fight to end lung cancer. Saving lives is possible right here, right now.