Opinion

Amid an overdose epidemic, we must make drug use safer

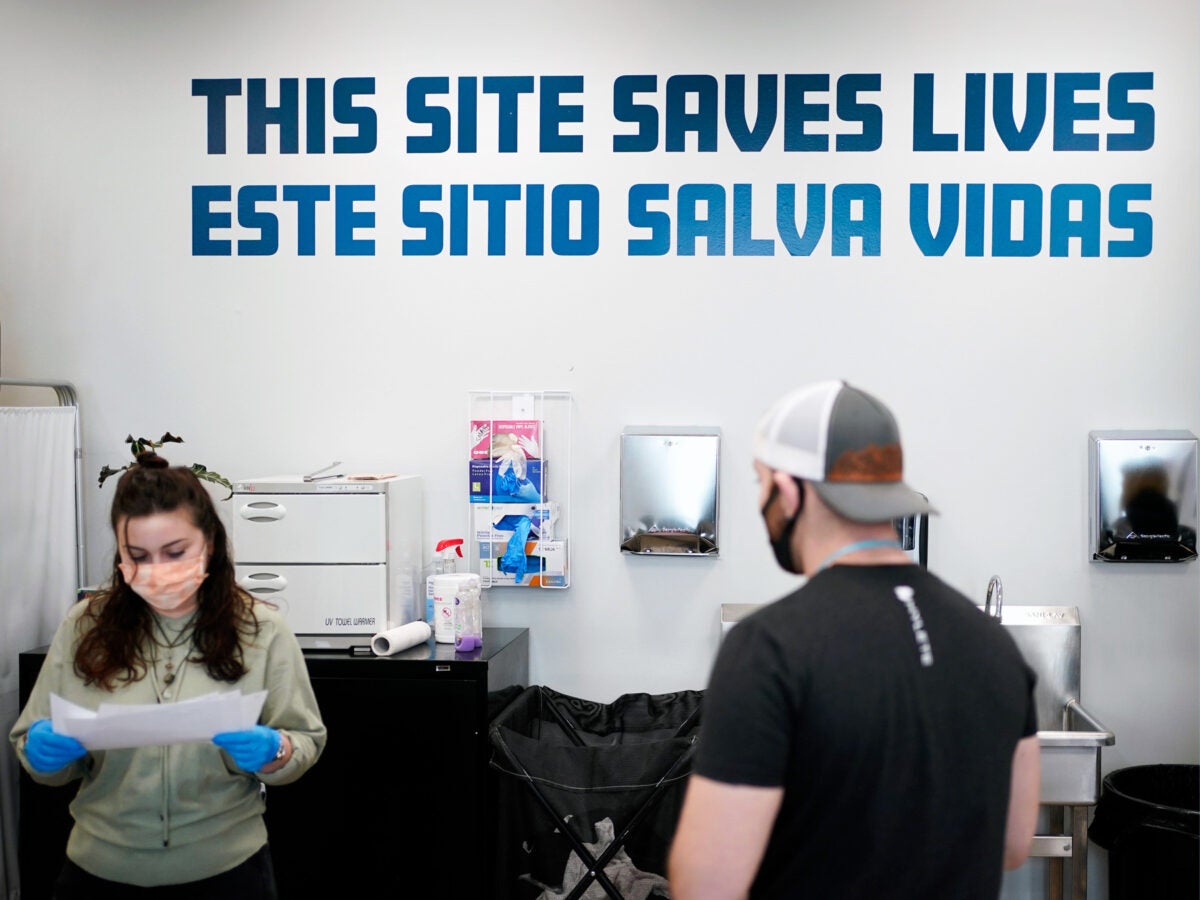

Last year, New York City’s health department made history by embracing a controversial approach to preventing deaths from drug overdose: overdose prevention centers, also called drug consumption rooms or safe consumption spaces.

In the U.S., we’ve long relied on the police and criminal justice system to deal with substance use. The current epidemic of overdose deaths shows that approach has failed. It’s time we turned the problem over fully to the public health system and harm reduction advocates. Overdose prevention centers – an intervention focused on reducing potential harms caused by drug abuse – are a key part of any strategy to curtail overdose deaths, and have been part of drug policy in Europe for decades.

Amid an overdose crisis topping 107,000 deaths in 2021, and worsening every year, these centers can save lives. President Biden’s drug czar, Dr. Rahul Gupta, has warned that yearly overdose deaths could reach 165,000 by 2025. Recent data briefs from the CDC have shown that Black and Indigenous people are experiencing the highest rates of overdose death, up 44 percent and 39 percent respectively in 2020 compared to the previous year.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

There are more than 200 centers operating around the world, after the first center opened in Switzerland in 1986. People who visit these centers can use any drugs they’ve brought themselves, usually via injection or smoking, with sterile and new equipment to prevent infections like endocarditis. Trained staff – peer workers, nurses, or EMTs – circulate and watch for potential overdoses or other bad outcomes. They also can engage with visitors and provide support and education around safer drug use. Many sites have on hand oxygen support and naloxone (an emergency medication that can reverse opioid overdoses). Eliminating the need to wait for emergency services is both more effective and a more humane approach to preventing and treating overdose.

Overdose prevention centers do not just prevent overdose deaths. Many offer counseling and treatment resources, with some even offering treatment like buprenorphine on demand. Typically integrated with other harm reduction services, they also provide people who use drugs with access to sterile syringes and other supplies to stem potentially deadly infections. Nearly half of visitors to the New York City prevention centers received this additional support as well. Offering these services in a welcoming environment fosters improved health and longevity at both the individual- and community-levels.

Recently published data on the first two months of operation in New York City revealed promising results.

More than 600 New Yorkers visited the centers within two months of opening. Staff intervened to treat overdose 125 times over two months; administering naloxone or oxygen to some, and simply monitoring breathing for others. The centers monitor people using various types of drugs, from opioids to stimulants like cocaine. A risk of stimulant use is “overamping,” which can lead to heart attack, seizure, or stroke. In addition to treating overdose, the New York City centers responded to 45 cases of overamping during the two-month period, providing hydration, cooling, and other support. Most importantly, out of nearly 6,000 visits, not a single person died.

Though the results are relatively early-stage, they support opening more overdose prevention centers – a potentially radical change to U.S. drug policy. The New York City study is backed by previous research on existing underground centers in the U.S. In one study of an existing unsanctioned center with more than 10,000 supervised injections documented, there were no deaths.

Even in their infancy as government-sanctioned sites, New York’s overdose prevention centers are already a critical tool to help alleviate the community toll of the now 50-year-long drug war. Yet they face significant obstacles, not least that under federal law they are still technically illegal. Obstacles like zoning laws, regulations, lack of funding, and especially stigma will continue to block their implementation across the country. In March, Rhode Island became the first state in the country to pass legislation sanctioning pilot prevention centers as overdose death rates soared. But Rhode Island communities could still block centers from being established in their neighborhoods at the local level. Just last week, Governor Newsom of California vetoed legislation allowing for pilot safe consumption sites.

However, the Biden administration—the first ever to publicly support a harm reduction approach—is poised to lead a pivotal shift in federal drug strategy. Advocates hope that the Office of National Drug Control Policy and the Justice Department will authorize prevention centers nationally, as part of the White House’s goal to reduce fatal overdoses by 13 percent over the next few years. Federal approval to open overdose prevention centers in communities nationwide would be a monumental asset in the face of local opposition.

Public health is about partnering with and protecting the most vulnerable among us, including people who use drugs. Simply put: as we face the worst overdose death crisis we have ever seen in the United States, why wouldn’t we try every tool we have in our toolkit to prevent deaths?

Top photo:

Employees and visitors inside OnPoint NYC, an overdose prevention center, in February 2022. Equipped and staffed to reverse overdoses, New York City’s new, privately run centers are a bold and contested response to a storm tide of opioid overdose deaths nationwide. (Seth Wenig / AP Photos)