Opinion

It’s not too late for Elon Musk to take Memphis’s environmental health seriously

In June, the Greater Memphis Chamber of Commerce made a surprise announcement that Elon Musk’s artificial intelligence company, xAI, would be building “the world’s largest supercomputer facility” in Memphis. Within days, people who live near the new facility began sounding the alarms. They were concerned about the risks it poses to public health—in their own community and beyond.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

It’s not hard to understand why Memphis, or other cities like it, would want an xAI computing facility built within its limits. Musk is lauded as a pioneer in clean energy—a leader in electric vehicles, electric charging infrastructure, and most recently, in deploying solar and energy storage. xAI’s Memphis facility is one of many AI data centers being built across the country—increasing energy demand at a time when the federal government is supporting new infrastructure and growth in clean electricity through the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. These new centers promise good-paying modern jobs, as well as an opportunity to put new clean energy to work.

But these promises come true only if growth is handled the right way. AI data centers have been criticized by environmentalists for their carbon dioxide emissions, dangerous waste byproducts, and extraordinary demands on our electricity and water systems. One estimate holds that global AI infrastructure will soon use six times as much water as the nation of Denmark, and another that more than 30 percent of Ireland’s electricity will be devoted to AI computing centers by 2026.

So far, the Memphis project is not a model of how to do much more than move fast and break things. As NPR recently detailed, critics are concerned the tool “has fewer rules than other AI chatbots and has been known for creating controversial deepfake images, such as Mickey Mouse as a Nazi and Kamala Harris in lingerie,” as well as more indifference to curbing misinformation.

And that’s just the technology; the physical impact of the facility has also caused concern. It’s being built in South Memphis, known for both historically Black neighborhoods and poor air quality. It will place significant demands on the city’s electricity and water systems, and the impacts on both could harm residents.

To address these problems, xAI has made only promises—to coordinate with the city’s electric and water utility on a greywater facility and to install at least 50 megawatts (MW) of large battery storage facilities. So far, the promises aren’t plans; they’re talking points on a one-page factsheet, which lacks any mention of a timetable or detailed construction plan. And there are few avenues for accountability: The company has held no public meetings, nor communicated directly with the media. City officials signed nondisclosure agreements in order to engage xAI in negotiations to bring the plant to Memphis.

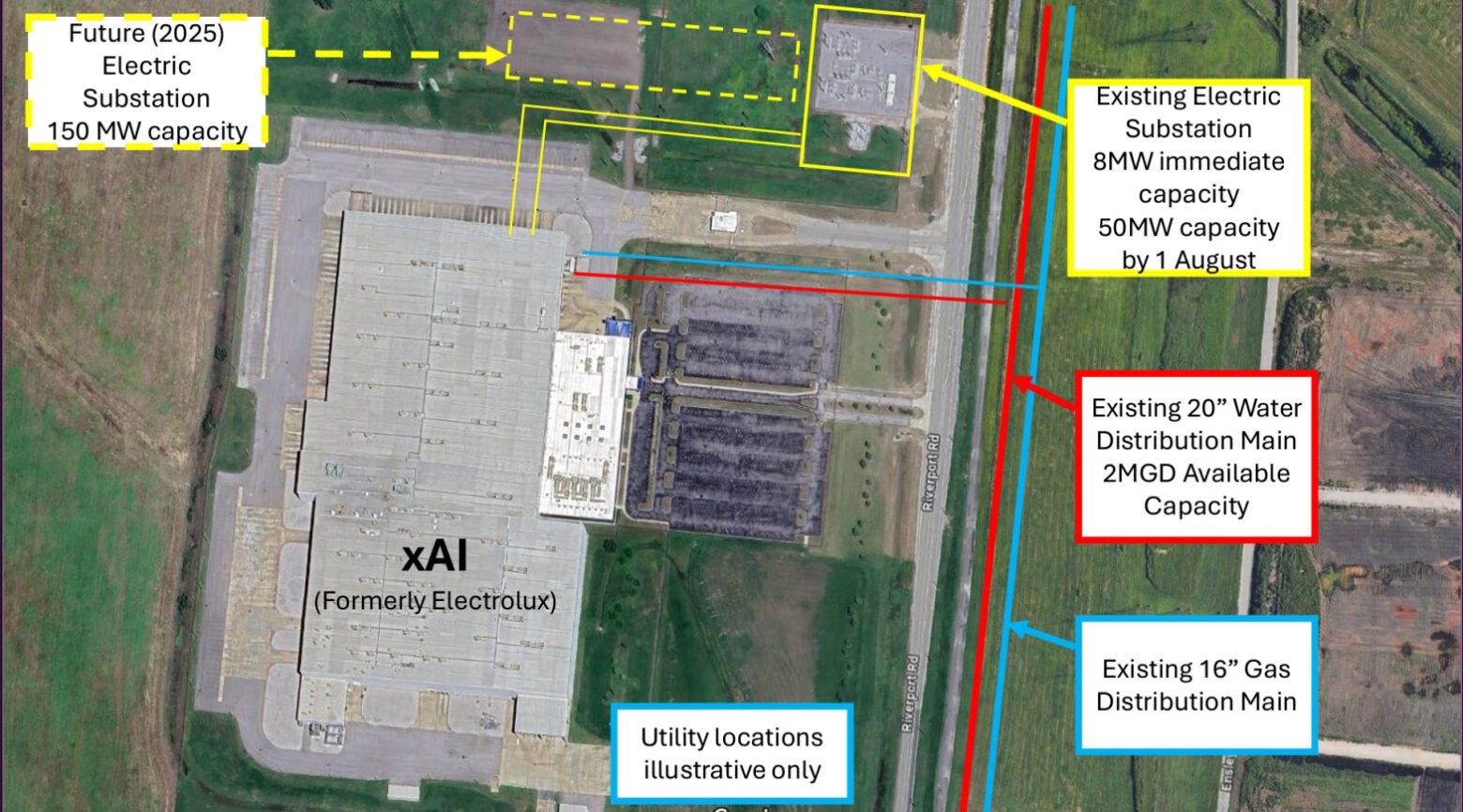

A map used in a presentation by MLGW at a July 9 Memphis City Council meeting to indicate some of the ways that xAI will use utilities.

MGLW via MLK50

Meanwhile, the project perpetuates the problems caused by decades of reactive management: higher prices for customers, a growing number of power outages, a lack of consideration for the people impacted by the new construction, and more. And while new power lines and water facilities are sorely needed in Memphis and elsewhere, the fact remains that work like this causes pollution.

In fact, xAI has already begun polluting—without the necessary permits, according to local environmental groups—in a neighborhood already burdened by legacy pollution from a coal power plant. And the supercomputer in question, Colossus, is already online, according to Musk’s social media account. If, as environmentalists fear, the plant affects the water supply, then the whole city will be harmed.

Still, it’s not too late for some meaningful relief to those impacted. For one thing, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), or more likely its Tennessee counterpart, TDEC, can and should immediately require xAI to stop burning gas until it has been issued appropriate permits.

Looking ahead, proactive grid planning could work more transparently to identify sites where projects like these would be less burdensome, or even more beneficial. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which supplies and regulates power in Memphis, has ultimate authority over whether and how to deliver the 150 MW of electricity xAI is asking to draw from the grid. This gives the TVA unique leverage: It has an opportunity to call for planning that considers the electric, environmental justice, and public health impacts of high-consumption projects. As other data centers go up around the country, local utilities will have their own chances to follow suit.

More broadly, construction and other industrial activities at Musk’s facility should be stopped until the community has been given a voice—through open processes conducted by state or local offices with authority over electricity planning (TVA), water system planning (MLGW), or environmental safety (TDEC). Subverting or ignoring these processes has already led to public outcry, but the true downsides—weaker infrastructure and higher rates of pollution, illness, and other maladies—can still be avoided.

Perhaps, as we all hope, this project will be a boon for the city, growing its economy and making it a technology hub—and a worthy model for future similar projects. But it won’t work if it breaks the rules. The AI boom needs infrastructure—water, power, people—to launch a brighter future. Taking shortcuts won’t make this happen—it will just make things easier for the rich and powerful, with the rest of us left to pay the cost.

Top image: A busy parking lot and rooftop cooling towers that are part of a recirculating chilled water system at the xAI facility can be seen from Riverport Road. (Andrea Morales for MLK 50)

Republish this article

<p>So far, he's not doing much more than moving fast and breaking things.</p>

<p>Written by Ben Adams</p>

<p>This <a rel="canonical" href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/environmental-health/xai-memphis-project-owes-city-more-than-promises-on-environment/">article</a> originally appeared in<a href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/">Harvard Public Health magazine</a>. Subscribe to their <a href="https://harvardpublichealth.org/subscribe/">newsletter</a>.</p>

<p class="has-drop-cap">In June, the Greater Memphis Chamber of Commerce made a surprise <a href="https://memphischamber.com/blog/general/velocity-meets-potency-xai-announces-memphis-as-new-home/" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">announcement</a> that Elon Musk’s artificial intelligence company, xAI, would be building “the world’s largest supercomputer facility” in Memphis. Within days, people who live near the new facility began sounding the alarms. They were concerned about the risks it poses to public health—in their own community and beyond.</p>

<p>It’s not hard to understand why Memphis, or other cities like it, would want an xAI computing facility built within its limits. Musk is lauded as a pioneer in clean energy—a leader in electric vehicles, electric charging infrastructure, and most recently, in deploying solar and energy storage. xAI’s Memphis facility is one of many AI data centers being built across the country—increasing energy demand at a time when the federal government is supporting new infrastructure and growth in clean electricity through the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. These new centers promise good-paying modern jobs, as well as an opportunity to put new clean energy to work.</p>

<p>But these promises come true only if growth is handled the right way. AI data centers have been <a href="https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/ai-has-environmental-problem-heres-what-world-can-do-about" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">criticized by environmentalists</a> for their carbon dioxide emissions, dangerous waste byproducts, and extraordinary demands on our electricity and water systems. One estimate holds that global AI infrastructure will soon use <a href="https://arxiv.org/pdf/2304.03271" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">six times as much water as the nation of Denmark</a>, and another that <a href="https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/6b2fd954-2017-408e-bf08-952fdd62118a/Electricity2024-Analysisandforecastto2026.pdf">more than 30 percent of Ireland’s electricity</a> will be devoted to AI computing centers by 2026.</p>

<p>So far, the Memphis project is not a model of how to do much more than move fast and break things. As NPR recently <a href="https://www.npr.org/2024/09/11/nx-s1-5088134/elon-musk-ai-xai-supercomputer-memphis-pollution" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">detailed</a>, critics are concerned the tool “has <a href="https://www.npr.org/2024/08/16/nx-s1-5078636/x-twitter-artificial-intelligence-trump-kamala-harris-election" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">fewer rules than other AI chatbots</a> and has been known for creating <a href="https://www.theguardian.com/technology/article/2024/aug/14/musk-ai-chatbot-images-grok-x" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">controversial deepfake</a> images, such as Mickey Mouse as a Nazi and Kamala Harris in lingerie,” as well as more <a href="https://www.npr.org/2024/08/16/nx-s1-5078636/x-twitter-artificial-intelligence-trump-kamala-harris-election" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">indifference to curbing misinformation</a>.</p>

<p>And that’s just the technology; the physical impact of the facility has also caused concern. It’s being built in South Memphis, known for both historically Black neighborhoods and poor air quality. It will place significant demands on the city’s electricity and water systems, and <a href="https://www.commercialappeal.com/story/news/local/2024/06/12/mlgw-energy-concerns-plans-elon-musk-xai-supercomputer/74019622007/" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">the impacts on both could harm residents</a>.</p>

<p>To address these problems, xAI has made only promises—to coordinate with the city’s electric and water utility on a greywater facility and to install at least 50 megawatts (MW) of large battery storage facilities. So far, the promises aren’t plans; they’re talking points on a <a href="https://www.mlgw.com/images/content/files/pdf/PDF2024/2024xAI%20and%20MLGW%20Quick%20Facts%201a.pdf" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">one-page factsheet</a>, which lacks any mention of a timetable or detailed construction plan. And there are few avenues for accountability: The company has held no public meetings, nor communicated directly with the media. City officials <a href="https://www.forbes.com/sites/amyfeldman/2024/07/22/elon-musks-mad-dash-to-build-a-power-hungry-ai-supercomputer-vinfast-graphyte/" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">signed nondisclosure agreements</a> in order to engage xAI in negotiations to bring the plant to Memphis.</p>

<p>Meanwhile, the project perpetuates the problems caused by decades of <a href="https://www.brattle.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2021-10-12-Brattle-GridStrategies-Transmission-Planning-Report_v2.pdf" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">reactive management</a>: <a href="https://newjerseymonitor.com/2024/08/21/market-problems-poor-planning-causing-price-hikes-in-nations-largest-electric-market-critics-say/" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">higher prices for customers</a>, a growing number of power outages, a lack of consideration for the people impacted by the new construction, and more. And while new power lines and water facilities are sorely needed in Memphis and elsewhere, the fact remains that work like this causes pollution.</p>

<p>In fact, xAI <a href="https://dailymemphian.com/subscriber/section/neighborhoodssouth-memphis/article/45589/memphis-xai-is-burning-natural-gas-without-a-permit-no-one" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">has already begun</a> polluting—<a href="https://www.environmentenergyleader.com/stories/as-musks-memphis-supercomputer-launches-concerns-raised-over-xais-gas-turbines-and-air-permit,48419" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">without the necessary permits</a>, according to local environmental groups—in a neighborhood <a href="https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2022/08/19/tennessee-valley-authority-memphis-coal/" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">already burdened by legacy pollution from a coal power plant</a>. And the supercomputer in question, Colossus, is<a href="https://x.com/elonmusk/status/1830650370336473253?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1830650370336473253%7Ctwgr%5E07422ee965c11aeea62f6af00775a54242e6b46d%7Ctwcon%5Es1_c10&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.npr.org%2F2024%2F09%2F11%2Fnx-s1-5088134%2Felon-musk-ai-xai-supercomputer-memphis-pollution" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener"> already online</a>, according to Musk’s social media account. If, as environmentalists fear, the plant affects the water supply, then the whole city will be harmed.</p>

<p>Still, it’s not too late for some meaningful relief to those impacted. For one thing, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), or more likely its Tennessee counterpart, TDEC, can and should immediately require xAI to stop burning gas until it has been issued appropriate permits.</p>

<p>Looking ahead, proactive grid planning could work more transparently to identify sites where projects like these would be less burdensome, or even more beneficial. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which supplies and regulates power in Memphis, has ultimate authority over whether and how to deliver the 150 MW of electricity xAI is asking to draw from the grid. This gives the TVA unique leverage: It has an opportunity to call for planning that considers the electric, environmental justice, and public health impacts of high-consumption projects. As other data centers go up around the country, local utilities will have their own chances to follow suit.</p>

<p>More broadly, construction and other industrial activities at Musk’s facility should be stopped until the community has been given a voice—through open processes conducted by state or local offices with authority over electricity planning (TVA), water system planning (MLGW), or environmental safety (TDEC). Subverting or ignoring these processes has already led to public outcry, but the true downsides—weaker infrastructure and higher rates of pollution, illness, and other maladies—can still be avoided.</p>

<p class=" t-has-endmark t-has-endmark">Perhaps, as we all hope, this project will be a boon for the city, growing its economy and making it a technology hub—and a worthy model for future similar projects. But it won’t work if it breaks the rules. The AI boom needs infrastructure—water, power, people—to launch a brighter future. Taking shortcuts won’t make this happen—it will just make things easier for the rich and powerful, with the rest of us left to pay the cost.</p>

<script async src="https://www.googletagmanager.com/gtag/js?id=G-S1L5BS4DJN"></script>

<script>

window.dataLayer = window.dataLayer || [];

if (typeof gtag !== "function") {function gtag(){dataLayer.push(arguments);}}

gtag('js', new Date());

gtag('config', 'G-S1L5BS4DJN');

</script>

Republishing guidelines

We’re happy to know you’re interested in republishing one of our stories. Please follow the guidelines below, adapted from other sites, primarily ProPublica’s Steal Our Stories guidelines (we didn’t steal all of its republishing guidelines, but we stole a lot of them). We also borrowed from Undark and KFF Health News.

Timeframe: Most stories and opinion pieces on our site can be republished within 90 days of posting. An article is available for republishing if our “Republish” button appears next to the story. We follow the Creative Commons noncommercial no-derivatives license.

When republishing a Harvard Public Health story, please follow these rules and use the required acknowledgments:

- Do not edit our stories, except to reflect changes in time (for instance, “last week” may replace “yesterday”), make style updates (we use serial commas; you may choose not to), and location (we spell out state names; you may choose not to).

- Include the author’s byline.

- Include text at the top of the story that says, “This article was originally published by Harvard Public Health. You must link the words “Harvard Public Health” to the story’s original/canonical URL.

- You must preserve the links in our stories, including our newsletter sign-up language and link.

- You must use our analytics tag: a single pixel and a snippet of HTML code that allows us to monitor our story’s traffic on your site. If you utilize our “Republish” link, the code will be automatically appended at the end of the article. It occupies minimal space and will be enclosed within a standard <script> tag.

- You must set the canonical link to the original Harvard Public Health URL or otherwise ensure that canonical tags are properly implemented to indicate that HPH is the original source of the content. For more information about canonical metadata, click here.

Packaging: Feel free to use our headline and deck or to craft your own headlines, subheads, and other material.

Art: You may republish editorial cartoons and photographs on stories with the “Republish” button. For illustrations or articles without the “Republish” button, please reach out to republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.

Exceptions: Stories that do not include a Republish button are either exclusive to us or governed by another collaborative agreement. Please reach out directly to the author, photographer, illustrator, or other named contributor for permission to reprint work that does not include our Republish button. Please do the same for stories published more than 90 days previously. If you have any questions, contact us at republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.

Translations: If you would like to translate our story into another language, please contact us first at republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.

Ads: It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads, but not ads specifically sold against our stories. You can’t state or imply that donations to your organization support Harvard Public Health.

Responsibilities and restrictions: You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third-party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. Harvard Public Health recognizes that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties aggregate or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

You may not republish our material wholesale or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You may not use our work to populate a website designed to improve rankings on search engines or solely to gain revenue from network-based advertisements.

Any website on which our stories appear must include a prominent and effective way to contact the editorial team at the publication.

Social media: If your publication shares republished stories on social media, we welcome a tag. We are @PublicHealthMag on X, Threads, and Instagram, and Harvard Public Health magazine on Facebook and LinkedIn.

Questions: If you have other questions, email us at republishing@hsph.harvard.edu.